We’re All Going To The World’s Fair combines adolescent dysphoria with haunting body horror

Quietly dropping on Shudder after scaring audiences at Sundance, indie debut We’re All Going To The World’s Fair evokes the terror and creeping sadness of lawness online settings. Eliza Janssen would definitely do the scary title internet challenge.

We're All Going to the World's Fair

Like some feature-length form of birth control, Bo Burnham’s coming-of-age black comedy Eighth Grade made me realise that if I were to ever have a child, they would inevitably be parented in some part by the internet. And the internet is a most toxic, manipulative mother to have.

Sure it’s taught me a lot, like any good parent should, and lets us form parasocial relationships that can weirdly feel more honest and intimate than the discomfort of IRL connection. Therein lies its danger, too. Within the anonymity of the web, impressionable young users are vulnerable to whatever dark communities and ways of thinking attract them, typically some corrosive combo of nihilism and loneliness.

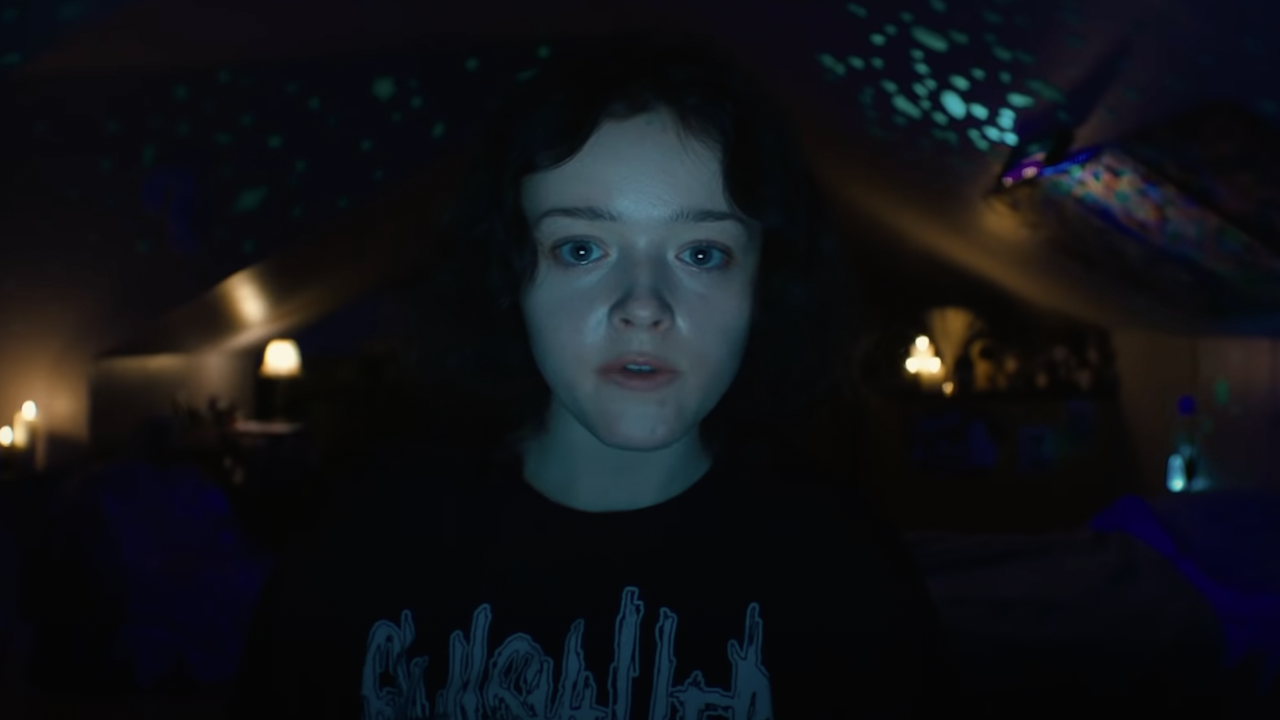

In Eighth Grade, Kayla’s mind falls prey to the lure of attention and fame. In We’re All Going To The World’s Fair, very similar character Casey (Anna Cobb) submits to a much more visceral kind of memetic corruption.

We instantly worry for Casey, noticing the teddy she’s too old to still be clutching and the looming parental presence in the background of her rural home that never gets close enough to appear onscreen. Cobb is crushing in the role, reminding you of every quiet kid in class who you simultaneously pitied and feared. So very alone, Casey falls asleep to the sound of an ASMR YouTuber clicking her acrylic nails together, whispering to her with maternal tenderness.

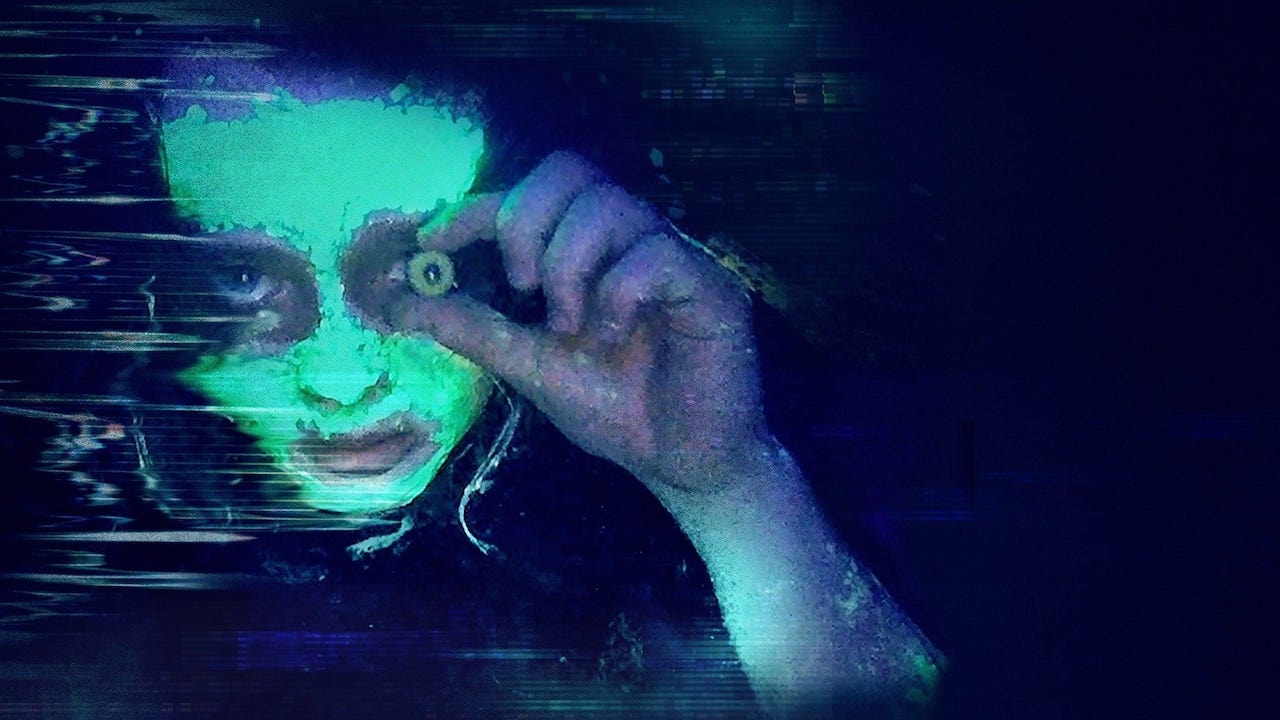

When someone out there in the online void does take notice, it’s by spamming Casey’s screen with a horrifying edited image of herself, eyes and mouth distorted. Casey’s ritualistic addition to a creepypasta meme, “the world’s fair challenge”, has got this grown-ass man’s attention.

What follows can be upsettingly oblique, ending on a mysterious note that will frustrate some horror fans (and indeed, the film’s score on Shudder has just two skulls out of five, with plenty of bored commenters rage-quitting on the film after mere minutes). For internet freaks of a certain age, though, the human (and post-human) story will cut to the quick, with strains of the same technologically-stranded loneliness that haunts Lake Mungo‘s found footage scares.

Director Jane Schoenbrun filmed We’re All Going To The World’s Fair as they were going through a tumultuous period of coming out as trans and non-binary, a period of change that should be joyful and autonomous repackaged through uncontrollable body horror and found footage eeriness in their feature film debut.

It’s never quite clear whether the symptoms of the spooky online “challenge” Casey sees in herself and other participants (like a boy who unspools fairground tickets from his arm, or the buff guy whose workout footage is titled ‘I CANT FEEL MY BODY!’) are imagined or horribly real, but they’re documented with the same zeal as many young transpeople archiving their “second puberty” online before an anonymous audience of supporters.

Maybe you need to have grown up online to appreciate the creeping sadness of Schoenbrun’s vision, or to be entertained by the quite funny, lo-fi memes that we’re confronted by each time a whirling “buffering” symbol appears in frame. To me, the film’s terror lies in its unpredictable, lawless online setting. It seems just as likely that a lonely emo teen would lie about a fantastical, scary transformation for attention, and also that such impossible trauma could quietly happen in some corner of our oversaturated social media landscape without anyone ever noticing.

There’s two terrifying scenes in particular that would’ve melted my brain as a kid, looking up traumatising stuff on my grandparent’s boxy PC. One is presented by JLB (Michael J Rogers), the middle-aged man who feeds into and feeds off Casey’s apparent supernatural metamorphosis. He sends her a webcam clip of her own sleeping face: running his cursor over her prone form, he can’t contain his excitement, “Casey, this is your scariest video yet. It’s like Paranormal Activity”.

We watch as her arm subconsciously pulls her body off the mattress, a mad grin spread across her face. It’s impossible to tell where JLB’s genuine belief and concern for Casey ends, and his hunger for her to keep entertaining and scaring him (and us) starts.

She seems more in control, ecstatically happy even, in the next scene. For perhaps the first time in the film, Casey smiles and laughs, jumping around to a goofy, seemingly original song “Love in Winter”. Until her hysterical screams suddenly drown out the weak MIDI karaoke track. And then just as suddenly, it’s back to the TikTok-esque dance moves, and lame lyrics about craving connection: “the snow is cold/my room is hot/are you watching it too/across this town?”

Speaking to Little White Lies, Schoenbrun elaborated upon the film’s themes of ephemerality, and where our vulnerable, fragile bodies lie in a space that can manipulate us at any moment: “Structurally, I wanted the film to feel like traveling from one bedroom to another, and in between we’re sort of lost in the haze of the internet…It would do a disservice to over-explain, [but] I think it has a lot to do with dysphoria and transness and loneliness.”

This disembodied feeling—of both gender dysphoria and of being victim to the internet’s dark ambiguity—is deeply upsetting in We’re All Going To The World’s Fair. It could be the worst possible coming-of-age film to show to an actual adolescent, as it might confirm all their identity-destroying nightmares about what selfhood and change look like. And yet like Eighth Grade, it’s painful to watch from the other side of your teenage years, too.

The film’s title invites every viewer to admit that we would be similarly unable to avoid meme-based annihilation if we were back in that agonising, tender time, poking at the gruesome results of our changes with fascination. And if we’re not Casey, then we’re her creepy viewer: forced to hunch forward and watch her gradual breakdown, unable to look away even if it’s our attention making the horrors real. Watch this one in the dark, then log off and touch grass for a while.

We're All Going to the World's Fair