Todd Haynes doco on The Velvet Underground is disappointingly conventional

The story of Lou Reed and John Cale is the centre of a new documentary about iconic band The Velvet Underground, which fans might finds a bit wanting, writes Amelia Berry.

Director Todd Haynes has always been fascinated by the seedier side of rock ‘n’ roll glamour, from barbie-based exploration of anorexia, Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story, through cult glam rock hagiography Velvet Goldmine, and artsy Dylan biopic I’m Not There (which netted Cate Blanchett an Oscar for Best Supporting Actress). It’s no surprise then, that Haynes’ first foray into documentary filmmaking should be about the seediest, the most mythologized of 60’s rock ‘n’ roll bands, The Velvet Underground. I mean, heroin, homosexuality, Andy Warhol? Pretty juicy stuff.

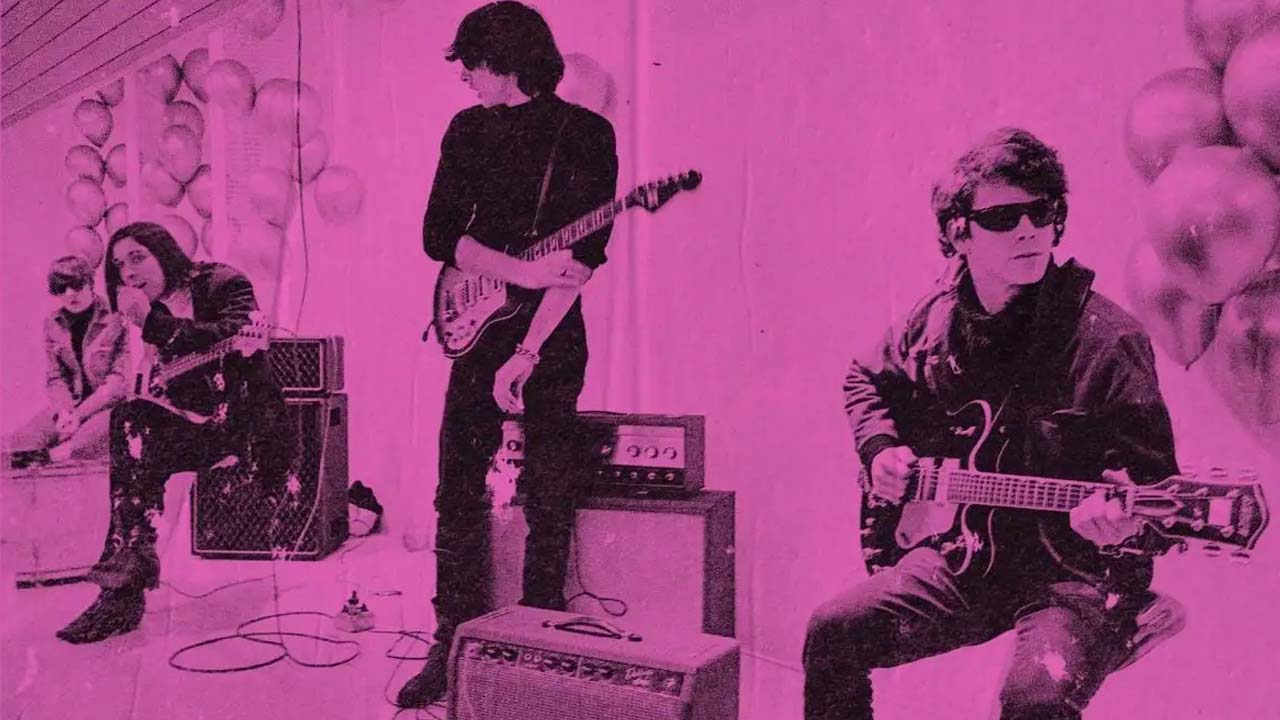

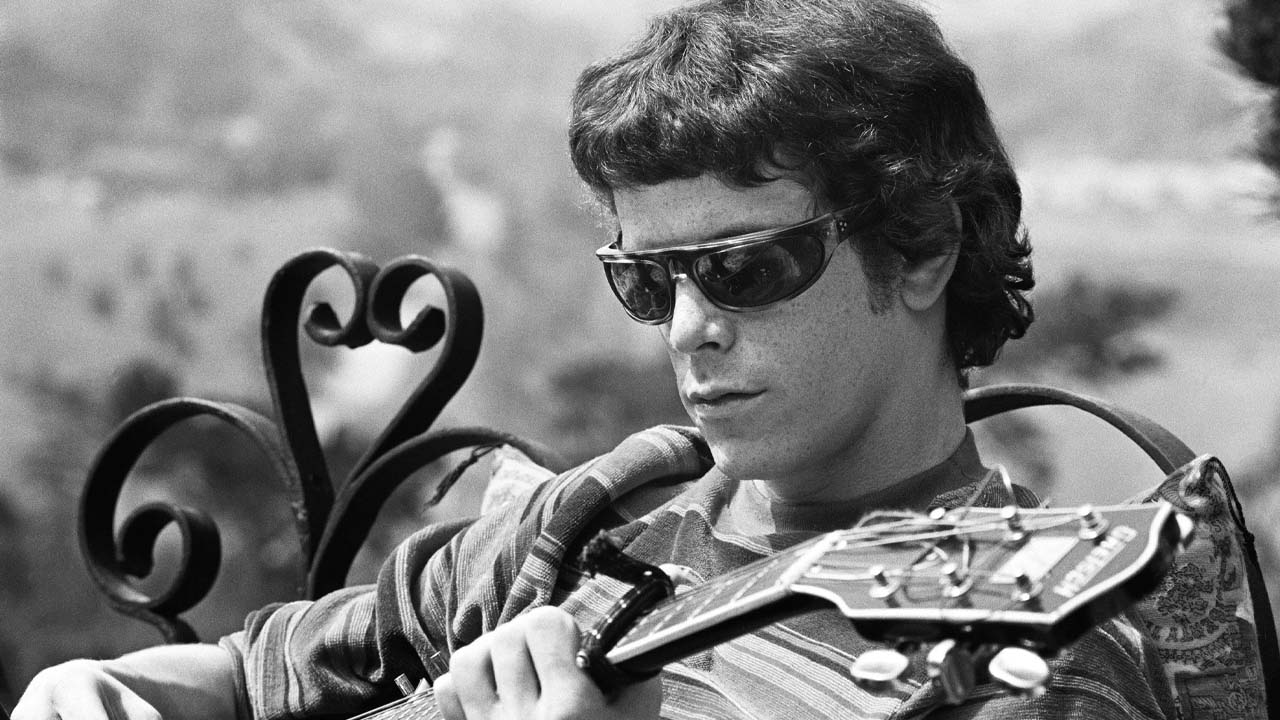

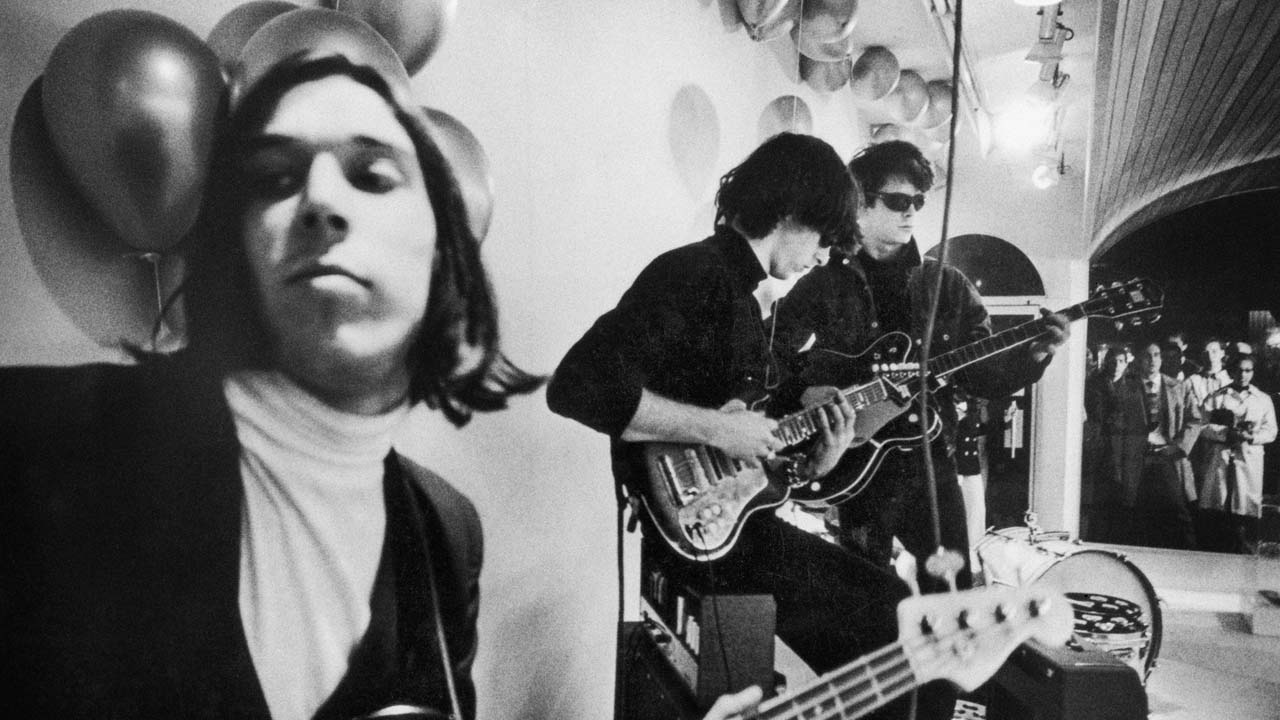

Right from the get-go, it’s clear that Haynes isn’t interested in telling the story of The Velvet Underground as such. The band doesn’t even get together until 40 minutes in. Rather, this is the story of Lou Reed and John Cale, the rock ’n’ roll songwriter, and the avant-garde viola player who represent the competing creative drives of the band for their first two albums.

The film gives Reed and Cale the full this-is-your-life treatment, following both from birth. While Cale narrates his own early years in his captivating Welsh drawl, Reed (who passed away in 2013) has his story told by his sister Merrill Reed Weiner and school friend and biographer Allen Hyman. Neither has anything particularly compelling to say, and Hyman in particular seems very uncomfortable with the more salacious aspects of Reed’s life. If we’re to believe Hyman, the reason Lou Reed spent so much time in gay bars as a teenager is because he enjoyed the charming atmosphere.

The film feels at its most confident flitting through the avant-garde of mid-60s New York, touching on Ya Monte Young’s Dream Syndicate musical drone collective, and the experimental cinema of Jonas Mekas. Andy Warhol, who took the band in, bankrolled their first album, and designed it’s iconic “banana” cover, gets a lot of screen-time (mostly montages).

It all feels like classic 60s doco stuff, mythologising the grubby into the grandiose. And for what it is, it’s very good, effectively setting up the world of The Velvet Underground as a dark, high-brow alternative to shallow West Coast hippie flower-power. It’s hard to beat Cher saying saying “[The Velvet Underground] will replace nothing, except maybe suicide”.

As Cale exits the group in 1968, the band moves away from the New York avant-garde scene and Haynes seems to lose interest a bit, glossing over the rest of the rest of the band’s output, and mentioning Cale’s replacement Doug Yule, only in the most brief and derisive terms. This is a shame, as this period produced the band’s two best-known commercial hits “Sweet Jane” and “Rock and Roll”, and though we get nods to fan-favorite cuts “Candy Says” and “After Hours”, it all feels like a bit of an afterthought.

The saving grace of this section of the film (the last half hour or so), is Jonathan Richman who recounts with much glee and charisma his devotion to the band as a teenager, seeing them upwards of fifty times. His appearance, along with John Waters and La Monte Young (looking like a leather daddy Rip Taylor), inject a lot of brightness into what is otherwise a pretty dour story told by very jaded people.

Fans of the band will likely find this documentary a bit light, particularly if you’re interested in guitarist Sterling Morrison, drummer Moe Tucker, or (god forbid) the man who would more-or-less lead the band in its final era, Doug Yule. It’s also a little disappointing that Todd Haynes has delivered such a conventional music documentary, but if you set your expectations a bit more Prime Rocks and bit less Velvet Goldmine, then The Velvet Underground is a solid movie for a Friday night in.