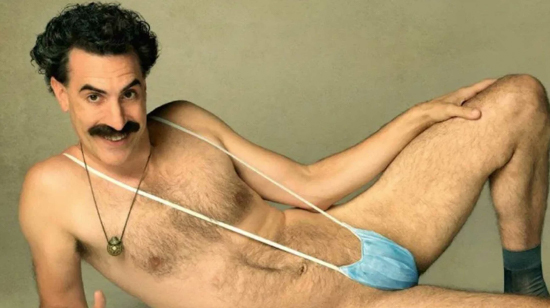

Subsequent Moviefilm review: Can Borat still shock us?

The novelty of the original movie has waned, but the Borat sequel (landing on Prime Video this week) proves Sacha Baron Cohen’s twisted creation still has a purpose, writes critic Luke Buckmaster.

Sacha Baron Cohen has always been a comedian who relishes catching people off guard, whether these people are his viewers or shocked and bemused parties in his presence—laughing along, or recoiling in horror, or waiting for the cartoonish idiot in front of them to stop talking. And so….surprise! A few weeks ago none of us even knew a Borat sequel was in the works, let alone about to drop, and ta-da, here it is, very nice: a follow-up to the comedian’s 2006 pièce de résistance of off-colour pranksterism, with Cohen reprising his role as the titular bone-headed Kazakh TV journalist.

As a character Borat is unintentionally offensive within the narrative world and very intentionally offensive in ours. The ghastliness of Cohen’s pantomime serves a higher purpose: to illuminate the prejudices of everyday Americans, from frat boys to conservative Christians and cowboy hat wearing rednecks. He punches up (exposing ignorance and critiquing power) by punching down (using racial caricature), which confuses everybody, inevitably triggering discussions about ends justifying means and launching conversation number five billion forty-seven about where ‘the line’ is in comedy.

The novelty value has worn off in Borat Subsequent Moviefilm, an, erm, moviefilm tasked with surprising within a now established space, etched out with familiar routines and setups. The comedy still entertains but isn’t as in-your-face, in the same way that listening to Donald Trump no longer carries the same sort of visceral shock it did when most of us started hearing his petulant, South Parkian whine four or so years ago.

Audiences become accustomed to grotesquery, which poses challenges for Cohen. Does he adjust the scales by ratcheting up the gross-out factor—and if so, how do you get grosser than, say, the elephant vagina scene in Grimsby? Does he become cruder and pointier politically—and by what means could this possibly be achieved, when Trump is a nastier invention than anything he’s going to come up with? Does Borat simply continue to ply his trade—head down, arse up—in the hope of cutting through 2020’s cacophonously loud media landscape?

Cohen, director Jason Woliner and all the writers returning from the first movie choose the latter, kicking off the sequel with the protagonist in the gulag, punished for crashing Kazakhstan’s economy and making the country an international laughing stock. Borat comes back to America in an attempt to make things right, his daughter Sandra (Irina Novak) in tow, who he plans to present as a gift to “Premier McDonald Trump” or another high-ranking Republican. She acts as his partner in crime, and somebody for Cohen to bounce off, as Borat’s obese friend Azamat (Ken Davitian) was in the predecessor.

Borat is recognised in America, however, requiring him to wear various disguises—a neat way of addressing a problem Cohen himself encounters. An early escapade shows him getting kicked out of an event Mike Pence is speaking at while in a fat suit dressed up as Donald Trump, in a stunt that doesn’t go anywhere; the writers didn’t work out a resolution any funnier than the comedian simply being ejected from the building.

Cohen reportedly remained in character for five days for a more entertaining segment later on, bunkering down with two Americans from the south, Jim and Jerry: charming fellows—described by Borat as “two of America’s greatest scientists”—who have heard, and sincerely report, that the Clintons drink blood, because QAnon. Cohen understands it’s tough to parody these sorts of people; he lets them speak for themselves.

Or better yet: let them sing and chant along with one of the comedian’s monstrous creations, during knee slapping musical numbers configured to lure people into co-conspirator status, their, shall we say, provincial beliefs on full display. In Borat Subsequent Moviefilm (just repeating the film’s title feels like falling for one of his routines) the protagonist, dressed up as a bumpkin named Country Steve, fronts the crowd at a far right rally, performing a song with a chorus repeating the line “coronavirus is a liberal hoax.”

You’ve seen this sort of thing before, and seen it better—in the first Borat movie, for instance, during the famous Star Spangled Banner rodeo scene, and in funny sketches such as Throw the Jew Down the Well, which now exists in front of an even more alarming real-life backdrop, given the horrible rise of anti-semitism across the world in recent times. But the results are still shocking—more than any of the dick jokes or gags about a woman’s “vazhïn”—because it’s rooted in a terrible real worldness that has, at its core, nothing to do with the comedian; he’s just the force that draws it to the surface.

Cohen wore a bulletproof vest when he attended the far right rally, held in Washington by a group called the Three Percenters, attended by scary looking heavily armed dudes. Somebody in the crowd with a dumb grin on his face performs a Sieg Heil salute and Jesus, as they say, wept. Moments like these that arrive with a sense of timeliness are the most urgently funny, though an annoyingly large swathe of the action is focused elsewhere, on Borat and Sandra (whose hero is Melania Trump) traipsing across America—doings things like visiting a hardware store to buy a cage, because that’s where the film says women are kept in Kazakhstan.

Entrenched misogyny is a broad subject to satirize, and generally speaking the broader it gets the baser it gets. Cohen’s schtick works better when his targets are more specific; even just when they’re right in front of him—like one famous American politician who is ensnared hook, line and sinker towards the end, and comes away looking very sleazy and gross indeed. The sick shimmer of the original movie has lost some of its freakshow appeal, but Borat—as a character, as a franchise, and dare I say it, as a journalist—still has a purpose.