Obi-Wan Kenobi realises the full potential of Ewan McGregor—and franchise innovation

Somewhere between fandom pandering and genuine emotional richness, Obi-Wan Kenobi managed to impress prequel trilogy defender Clarisse Loughrey after only a few episodes.

Star Wars has become the ouroboros—the snake eating its own tail, caught in an infinite cycle. The trilogies all repeat the same story: darkness rises and light to meet it. Fear leads to anger, then to hate. A rebellion is built on hope. The fandom, meanwhile, circles round and round familiar arguments. The Empire Strikes Back was hotly disputed on release. Now it’s commonly cited as the best Star Wars film ever made. The prequels were met with disdain, only to be revived by the meme-literate generation that grew up with them.

I’m of said generation. I first saw The Phantom Menace at the age of eight, and used to carry around a doll of Queen Amidala like it was an exterior organ.

Since then, my feelings about prequels have existed in a state of constant fluctuation, as I try to square up my nostalgia with that red-underlined list of unavoidable flaws. Why is so much of the trilogy dedicated to the ins and outs of trade negotiations? And why does the only lead female character simply choose to die out of convenience?

But, that said, I’ve always been drawn to George Lucas’s own perception of his intergalactic creation—that Star Wars should be pure space opera, driven by a fierce battle between loyalty and personal desire. Who decides the righteous path? And who does the righteous path benefit? After all, Anakin’s seduction by the dark side began with the Jedi council’s refusal to help his enslaved mother on Tatooine, as it was deemed none of their concern.

So far, I’d looked to Disney+’s Obi-Wan Kenobi series—which adds an epilogue to the prequels, set ten years later and helping to bridge the gap that eventually leads to A New Hope—with a healthy dose of scepticism. I’ve been ready to move on from the Skywalkers for some time now, and I think the explosive popularity of the (largely) non-Skywalker-centric The Mandalorian suggests that general audiences may feel the same way, too.

From a cynic’s perspective, Obi-Wan Kenobi is nothing but a victory lap for Star Wars’s rehabilitation of the prequels, subtly and not-so-subtly encouraged by Disney. The series premiered in tandem with Star Wars Celebration, an official convention that featured a 20th-anniversary panel for Attack of the Clones this year.

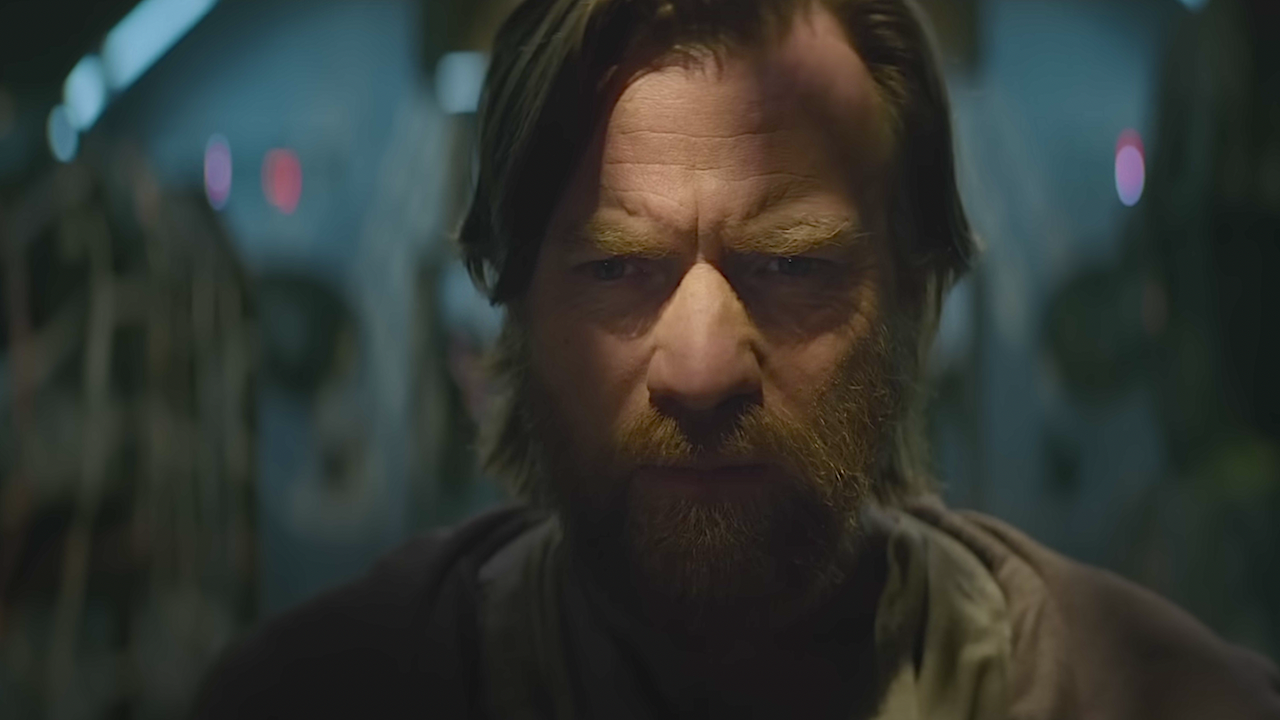

Ewan McGregor’s Kenobi was, arguably, the most unblemished element of prequels. He never took the thing all that seriously (see: “hello there”), which, in turn, excused him from much of the vitriol. The whole point of nostalgia is that it functions on purely emotional, somewhat undefinable terms—and so, the first time we see McGregor, back and bearded, with a careworn expression on his face, something stirs.

The actor was already well-cast back in The Phantom Menace, but that potential only really comes to full fruition here. Lucas was always clear that the prequels were a tragedy, and Obi-Wan Kenobi opens tellingly on a shot of younglings fleeing for their lives, made targets by Order 66 and its command to wipe the Jedi order off the face of the galaxy.

The Kenobi we left behind in Revenge of the Sith was an utterly broken man, his belief system razed by the loss of Anakin (Hayden Christensen, also set to return), the friend and protegé he loved so dearly. And McGregor wears that loss beautifully here. There’s a sense of self-denial, too: in the first two episodes, that premiered together on Disney+, we never see him wield his lightsaber.

Instead, he throws punches that make his body ache. For all the ways Star Wars has clobbered its audience over the head with their own childhoods—for every CGI-deepfake Luke Skywalker and “somehow, Palpatine returned”—it’s also found a few ways to delicately mine the emotional richness of its own past for new material.

Obi-Wan Kenobi leans more towards the latter than the former. Series director Deborah Chow has allowed for touches of Lucas-ness, without obviously or carelessly replicating the very same self-indulgences the sequels were criticised for. We’re talking again about emotions in the extreme—of Kenobi bitterly declaring to a runaway Jedi (Uncut Gems filmmaker Benny Safdie) that “the fight is done, we lost”, only to then find his match in a villain of equal resolute.

Reva Sevander (Moses Ingram), the Third Sister and Jedi hunter, wants what she’s owed—an audience with Darth Vader himself. There’s a parallel here to Rogue One’s Director Krennic (Ben Mendelsohn). Both are dangerous precisely because they have so much to prove. It’s a reliably compelling character trait.

So where to place Obi-Wan Kenobi in the Star Wars scale of crass pandering to genuine innovation? Undoubtedly the show’s most controversial element will be the one that, so far, has been casually kept under wraps—that Kenobi’s story isn’t about young Luke, as we thought, but young Leia, after she’s stolen away from her home planet of Alderaan by bounty hunters. There’s an obvious logic to it: here’s an attempt at Grogu 2.0, with another classic character made cute and smaller. It’s a surprise only that the Disney era is yet to roll out a baby Wookie.

That said, baby Leia’s appearance, as played by Vivien Lyra Blair, doesn’t feel particularly grating—she’s well-written and well-performed, overflowing with that trademark sass (“All I ever do is wave”, she grumbles to her parents). She’s also the reason we finally get to have a Star Wars show that isn’t perpetually trapped on Tatooine. Not only do we see more of Alderaan pre-Death Star annihilation, but are introduced to an entirely new planet, Daiyu—part of a recent, and welcome, shift to incorporate more cyberpunk aesthetics into Star Wars, following The Book of Boba Fett’s pod racers.

More importantly, baby Leia, in the grand scheme of things, fits nicely into Disney’s attempts to readdress how the character’s been treated by the franchise. When Bail Organa (a returning Jimmy Smits) points out to Kenobi that his adopted daughter is “as important” as Luke, viewers should be immediately reminded of Yoda’s utterance of “there is another” in The Empire Strikes Back. Leia, if things had gone a different way, could have been the one duelling lightsabers with Vader in Bespin.

I guess Obi-Wan Kenobi proves that, even when the Skywalker saga seems all tapped out, there might still be a few stories left to tell.