IF’s cuddly characters are only imaginary, but the pain of watching them is real

John Krasinski swaps scares for family-friendly fantasy in IF, an attempt at Spielberg or Pixar’s childlike wonder. The film’s imaginary friends are an annoyance rather than heartwarming spectacle, says Luke Buckmaster.

“What if imaginary friends were real?” asks the marketing tagline for IF. Then I suppose, they wouldn’t be imaginary? Not long into this intentionally old-fashioned kids movie from writer/director John Krasinski, which shoots for an earnest Spielbergian glow but arrives somewhere deflatingly twee and saccharine, I came up with a better question: why do magical “kindly beast” characters in American movies tend to look so similar?

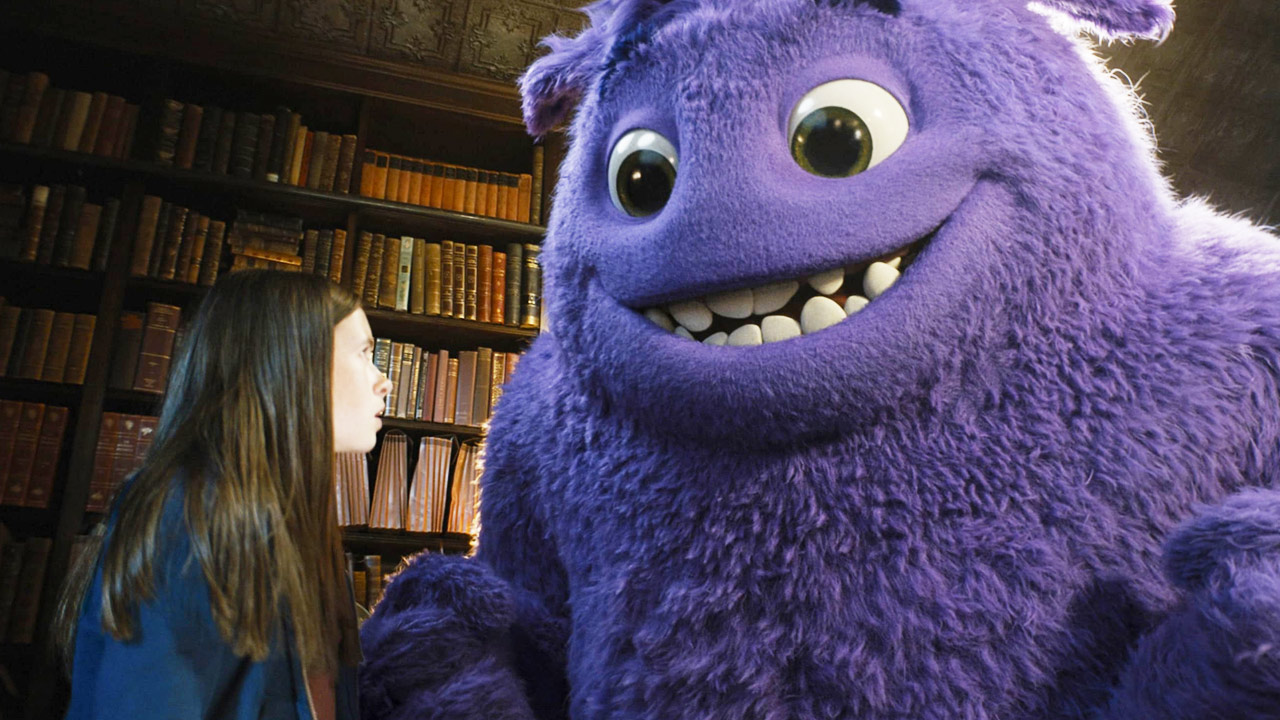

Steve Carrell is the voice of a huge purple glob of CGI named Blue, who has massive friendly eyes and curved teeth, his appearance mulching together the fluffy flesh of a zillion merchandise-friendly creations: a touch of Grimace, a splash of Sully, a dash of rumpusing Wild Things. Blue is an “IF”, who are imaginary (but…real) friends to children who’ve grown up and moved on, leaving them stranded in a magical creatures retirement home.

Now purposeless, with an eternity of time on their hands, some observe their former besties up close, with a Norma Desmond-esque longing for what once was, albeit observing from the other side of the astral plane—the angels in Wings of Desire via the factory from Monsters, Inc.

The film’s plot, which is both very simplistic and unnecessarily scrambled, follows 12-year-old Bea (Cailey Fleming) who has the power to see IFs and attempts to reunite them with their humans, who are now stressed-out New Yorkers. Helping her is Cal, the person who runs the retirement home, played by Ryan Reynolds with what strangely comes across as deliberate flatness: this guy is so familiar with the fantastical he sees no wonder, and has no spark in his eyes. I began to view the IFs as he does: merely functional aspects of this world, like chairs around a dinner table.

The film’s emotional essence lies in the relationship between Bea and her father (Krasinski) who is very ill with an unspecified sickness. He’s one of those annoyingly happy-go-lucky people who tell you everything’s handy-dandy, even with a basketball-sized tumour or while they’re bleeding out from gun wounds. But I never bought that poor dad was ill in the first place; his sickness felt phoney and he looked and sounded tickety-boo to me. So much so, I began to wonder whether Krasinski might be building an M. Night Shyamalan style revelation that too is an IF, dreamt up by Bea to ease the pain of hanging out with Ryan Reynolds.

Most of the other IFs are more imaginatively designed than Blue, I must say, though they tend to feel drawn from specific cultural contexts—from a gangly Betty Boop offspring to a Paddington-like bear and a Slimer-esque green blob. Krasinski, who also wrote the screenplay, kind of has an excuse for déjà vu in his character design, in that the IFs are imagined by kids, who are invariably influenced by their upbringing, surroundings, belongings, Happy Meal toys etcetera. But this pop culture melange schtick has been done better many times before; ditto for stories about kids growing up and leaving their formative creations behind—most famously perhaps in the Toy Story movies.

Krasinski makes a straight-faced argument that the fantasies of youth should not be extinguished by passage into adulthood, but careful what you wish for: this was the premise of Ted, and that lead to bongs on the couch and excrement on the floor. There was a period, in the film’s second half, when I finally found myself beginning to be endeared and coming around to some aspects of it, but sadly this period was quickly over—like a cool shower on a stinking hot day.

Whenever the IFs started to glow—a visual embellishment signifying a reconnection with their human compadres—I must admit I wanted to assault them with the nearest blunt instrument. Especially Blue.