Retrospective: women’s desire propels Jane Campion’s underrated erotic thriller In the Cut

Amanda Jane Robinson looks at why the critically maligned In the Cut – starring Meg Ryan and Mark Ruffalo – now seems desperately ahead of its time in its examination of danger and desire.

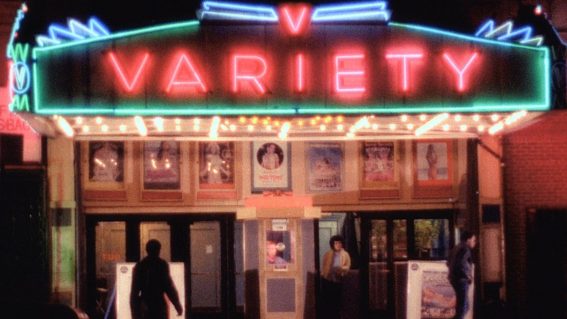

A bride waits for the subway while a few neighbourhoods over, a man beheads a woman. For women who have sex with men, violence abounds. It is one woman’s negotiation of this violence, the reconciliation of threat and desire, that drives Jane Campion’s long underrated 2003 erotic thriller In The Cut.

At the beginning of the film Frannie (Meg Ryan), an earnest English teacher passionate about poetry, is working on a project about slang with one of her students, Cornelius Webb (Sharrieff Pugh). She’s interested in slang for its relationship to sex and violence, and she’s interested in Cornelius for his proximity to new slang she hasn’t heard of yet.

While talking with Cornelius at a dive bar, she goes downstairs to find the bathroom, and instead spots a man in the shadows getting a blowjob from a woman with long blue fingernails. Instead of leaving, she watches, turned on. Days later, that woman’s disarticulated limb turns up in the garden outside her apartment, and a detective shows up at her door. The arrival of Detective Molloy, played with subtle excellence by Mark Ruffalo, irreparably disrupts Frannie’s orbit.

Until now, Frannie has had a routine, or rather, a rut. She cheers up her hopelessly heartsick sister Pauline (Jennifer Jason Leigh) and avoids the man she slept with once who won’t leave her alone (Kevin Bacon). She rides the subway, writing snatches of poems in her notebook, and masturbates because it’s easier to just think about sex than go through the rigmarole of getting it.

When she is asked out, Pauline encourages her to go whether she’s into the guy or not, “even just for the exercise.” She agrees and borrows a dress—she is desperate for some kind of jolt. Detective Molloy’s crudeness cuts right through her, and soon they’re sleeping together, despite her growing suspicions that he might be a murderer.

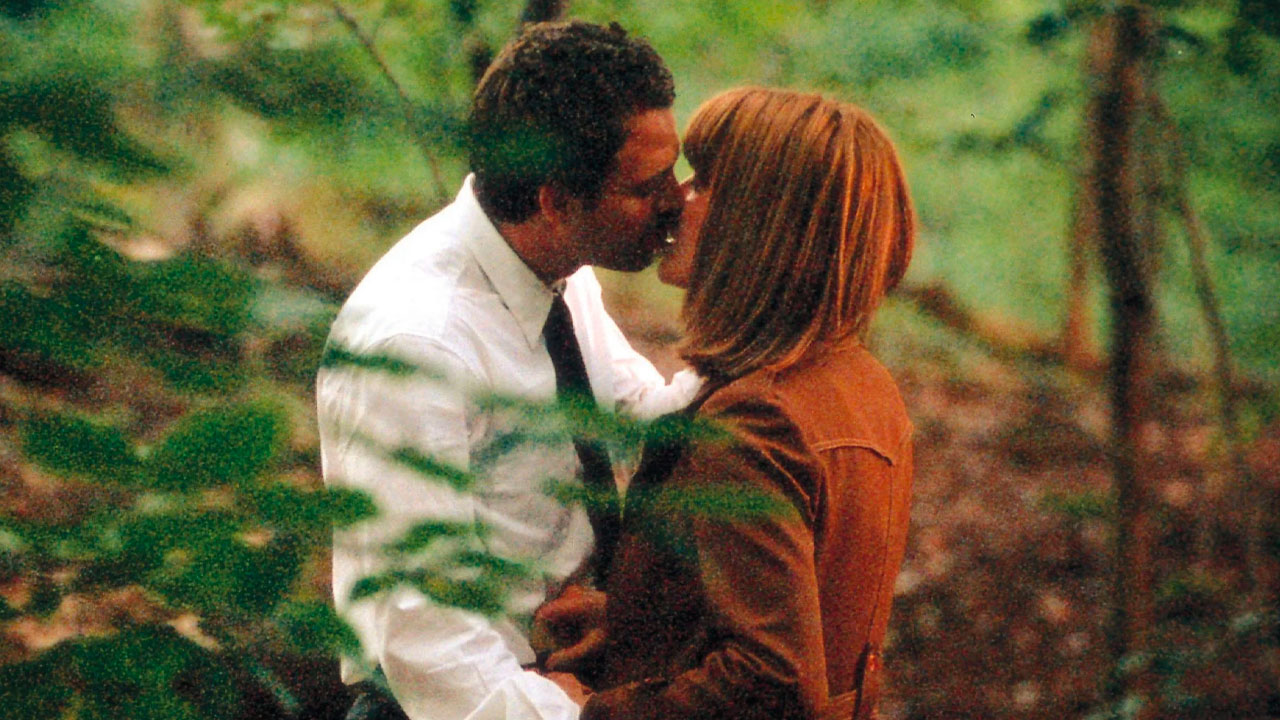

Occasionally Frannie will take steps toward caution—she calls the police department to verify Molloy’s credentials before letting him in her apartment—but knows that as a woman, she’ll never be entirely in control of her own security. What is there to do, then, but take the beauty with the brutality—the best sex of your life with a man who might kill you. Before Frannie and Molloy have sex, they discuss an attempted decapitation. During the sex, Frannie caresses her own neck. Marie Bardi called the film “erotic and dangerous, like a hand being held over a stovetop”. The threat inherent to pleasure, the pleasure inherent to threat.

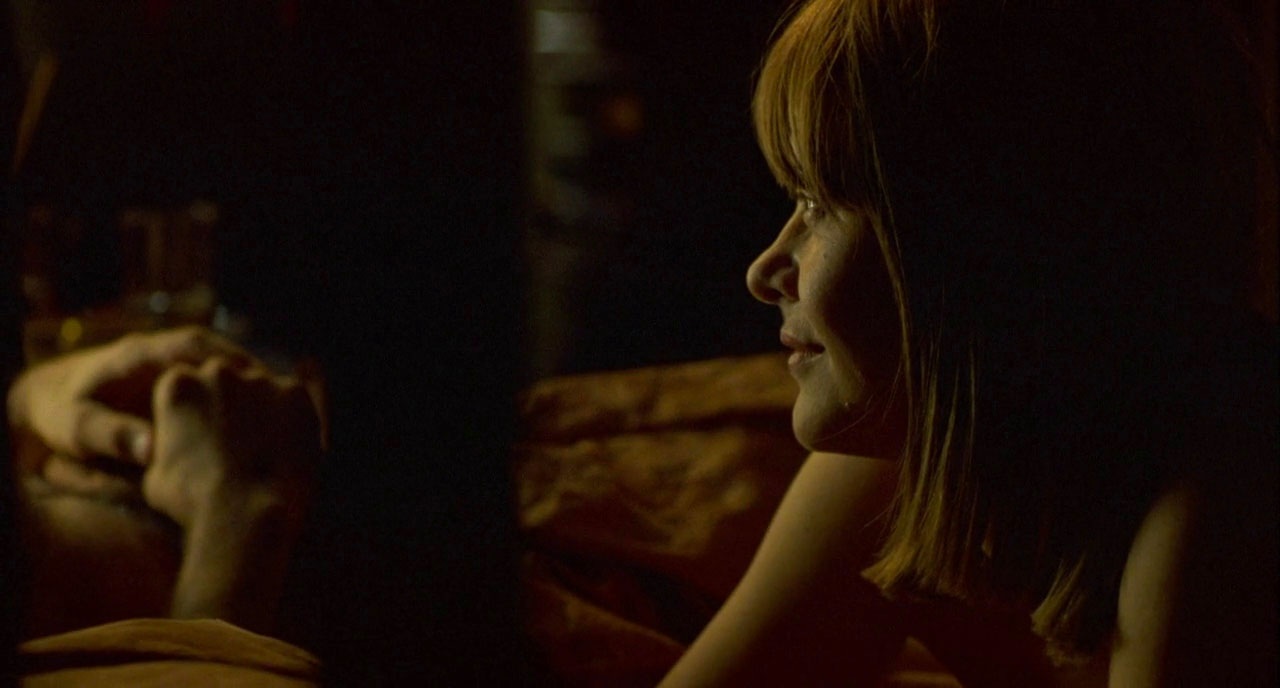

Much was made of the film’s sex scenes, with Meg Ryan’s full-frontal nudity commandeering the conversation upon the film’s release and affecting her career for sometime thereafter. A more interesting conversation, perhaps, concerns Frannie’s agency over her sexual relations, her frankness about her desires.

This is a woman who knows how to get herself off. The first time she and Molloy have sex, she figures what is about to happen and we watch her make a decision. He kisses her and her “all right” rings out like a starter pistol. She lies on her stomach so he can go down on her from behind; she nudges her foot towards him so he can take the hint and kiss it, bite it. She leads. Even before they have sex, her fingers linger over his name as she pins his business card to the wall. The chemistry is there, and she’s going after it.

When Pauline talks of Frannie letting Molloy sleep with her, Frannie replies: “I didn’t let him, I wanted to.” Even Molloy only learned to fuck so well because an older woman took him aside as a teenager and taught him. Women’s desire propels.

Besides the sex, there’s romance. A gauzy lens in a petal storm. Pauline pining over a married doctor. A “courtship fantasy” bracelet with a baby carriage charm. The killer’s signature is a wedding ring, after all. Frannie tells Pauline her father killed her mother, “when he left she went crazy with grief,” but sepia-toned proposal flashbacks show how good it was in the beginning. Is love worth the pain? In a bath scene, Frannie admits she’s scared of what she wants. “Why, is it a lot?” Molloy asks. “Yeah, it’s a lot,” she admits. Molloy thinks for just a second: “That’s the problem with you women, you can never be satisfied.”

Heavily inspired by Alan J. Pakula’s 1971 New York noir Klute starring Jane Fonda and Donald Sutherland, the film cleverly explores the relationship between Frannie’s lust and her paranoia. The closer she gets to fulfilling her fantasies, the more dangerous it all becomes.

Maligned upon release but seeing a resurgence in recent years, Kate Hagen describes In The Cut as “the last gasp of the 90s erotic thriller”. Messy of course—Campion’s approach to race has always been a little myopic— yet desperately ahead of its time, the best account of the film is from filmmaker Jessica Dunn Rovinelli: “at once a schematic of desire and the transmission of that desire from subject to viewer”. Campion originally pitched the film as a grim serial killer mystery in the vein of David Fincher’s Se7en, but lost out on funding when she turned in a script that drastically departed from the masculinity of traditional noir.

It is this departure that critics at the time so raucously condemned, but the film itself is as distracted—by questions of sex and romance and what it means to be a woman navigating the violence of men—as its characters, and that is its genius.

In behind-the-scenes interviews, Meg Ryan says she often felt during shooting like a silent film actress, that so much of Frannie’s character is her interiority. It’s all fear and ecstasy, intuition and tenacity. Watching the film, it’s the observation of this interiority, Frannie walking that knife’s-edge between danger and desire, that is the biggest thrill of all.