WETA chaps chat ‘Chappie’

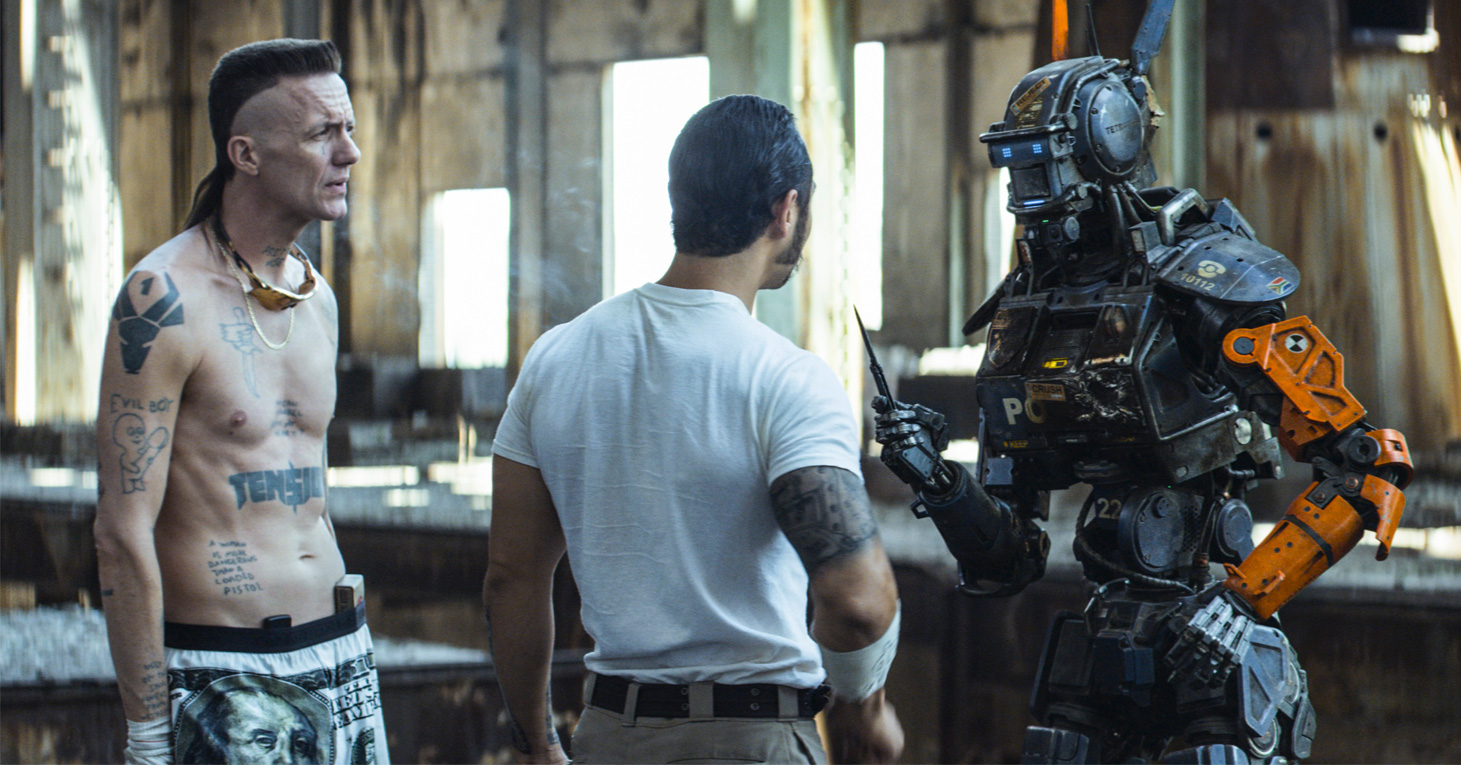

Neill Blomkamp brings another slice of South African sci-fi to cinemas this month with Chappie, the tale of a conscious robot taken under the wing of a couple of Johannesburg gangsters (played by South African hip hop duo Die Antwoord). Once again Blomkamp has continued his ongoing relationship with WETA, and last week WETA concept artists […]

Neill Blomkamp brings another slice of South African sci-fi to cinemas this month with Chappie, the tale of a conscious robot taken under the wing of a couple of Johannesburg gangsters (played by South African hip hop duo Die Antwoord). Once again Blomkamp has continued his ongoing relationship with WETA, and last week WETA concept artists and designers Greg Broadmore, Christian Pearce and Leri Greer joined us for a chat about how they brought this robotic character to life.

FLICKS: We’ve just seen the film. What an awesome character you guys created.

GREG BROADMORE: Thanks. We haven’t seen it yet, so you know more about it than we do [chuckles].

FLICKS: Excellent. There has obviously been a lot of talk about Neill Blomkamp’s ‘Alien’ project in the last few weeks, and one of the things I’ve found really interesting about that, besides the simple fact that it’s happening, was how much of an enthusiast he’s been, developing designs on a whim. Is he like that with the films you’ve worked on with him, as well?

GREG: I’d say so. Neill’s a fanboy, through and through. I believe after he studied CG, or whatever, he worked at an ad agency, which was Ridley Scott’s ad agency, so he’s had a connection with those films for a long time. I know that he’s a huge fanboy of Sigourney Weaver. I mean, who wouldn’t be? She’s amazing, and she’s an icon.

FLICKS: Are there differences between working with him and other filmmakers, because he’s happy to sketch up a concept and really advocate strongly for the way he thinks things should look?

CHRISTIAN PEARCE: We’ve got quite a long history with Neill, so we do have a pretty good understanding – almost in shorthand – of working with him. We’re all enormous fans of the same films, share a visual language and have a similar aesthetic. I don’t know how much of that we have learned from him now, or we just happen share with him. Since we’re all sort of raised on the same films and stuff, it does make easier to relate to him. He’s really quite personable to talk with as well. It’s not like you’re dealing with some big, scary director – he’s a guy, just like us.

GREG: We’ve been working with Neill since the Halo feature film that fell over, working maybe a year or more with Neill on that. Then we moved onto District 9, and then we did Elysium, and then Chappie, of course. In between that we’ve done a number of other small little projects with him as well. So, there’s a constant feedback loop.

While we’re all inspired by the same films, like RoboCop, Terminator and Star Wars, we’re also all inspired by the science and technology. I think that’s where a lot of it comes from. While there’s this total love of film, and inspiration from that, a lot of what drives us (and I know a lot of what drives Neill) is real-world science and happenings. For instance, when we were doing projects, he would send us videos and pictures of real-world robotics that are happening. He’ll geek out over that stuff.

We share around things like Boston Dynamics, which is a robotics company Google bought a while ago. They’re famous for their Big Dog Robot, which is absolutely incredible, quadrupedal robot that you’ve probably seen videos of. That kind of stuff is endlessly fascinating. If you want to make science-fiction films, you don’t really have to look far beyond those kind of videos to extrapolate and come up with new stories. You don’t have to look at old science-fiction to do that.

Also, the form often follows function, like in Neill’s films, we aren’t designing something that just looks cool. Usually, we’re trying to figure out the function of it and that dictates the way it looks. That’s the beauty of the real-world robots: the way they look, if they end up being cool, is almost by happenstance really.

CHRISTIAN: It’s probably something to do with physics and economy. You’re trying to strip away materials to reduce weight; these forms start to become beautiful unto themselves.

FLICKS: That’s also something that fits alongside the run-down environments and machinery in his films.

GREG: Totally. Star Wars is the film that defined ageing. Taking science-fiction and ageing it, making it still lived in and then Neill’s films, and other people’s films, have started to add on top of that. In Chappie‘s case, the gangsters that have taken possession of him cover him with graffiti, give him chains and things. Those are the kind of things that you wouldn’t necessarily see in other films. It starts to make him more interesting and not just a robotic form. You’ve got external culture imprinted on him, which is really fun.

CHRISTIAN: I think also when Neill was first making short films, they were done as if they were documentaries to give them impact. So he has a real documentary aesthetic, I think, through all his films. I think that also kind of ends up grounding things.

FLICKS: Of course the massive challenge in ‘Chappie’, as opposed to his previous films, is in really bringing a robot to life as a character. What different challenges did that present for you guys?

LERI GREER: One thing we really had to consider through his whole design was how he was going to be relayed on screen. We were working on Chappie as we were working on Elysium, and the droids in there were created in much the same way: filming actors live on set and then rotoscope a figure over the top. So, right from the start, we were kind of locked to a very humanoid form that, in this case, needed to be laid over Sharlto Copley’s character and without having to do a whole lot of digital removal, as in painting out the background actor. It needed to cover him as much possible, be able to move like a human, but without any cheating in there. It all has to be based on real robotics and real rigid form.

CHRISTIAN: And to that point, we made a physical chest rig for Sharlto. He wouldn’t be able to bring, say, his bicep as close to his chest as a person – he had to match what the robot could do. So we actually built physical restraints on Sharlto to make sure that was matching. For instance, if Chappie were to lean against something, instead of Sharlto’s skin being the thing leaning against it, it was the extent used to match Chappie’s shoulder or chest.

FLICKS: One of the moments that cracked me up was an upset, slouched Chappie emulating Ninja’s physicality.

GREG: Yeah. That’ll be Sharlto actually. He’s an amazing mimic and an expert at accents. He grew up in Johannesburg himself, in South Africa. He would have hung out with Ninja a lot and so that would be his performance. I haven’t actually seen that scene, but I’d love to see it.

FLICKS: It came to mind as you were mentioning those physical limitations placed on his performance by the suit because there’s something that isn’t quite right about it. It’s a robot, doing the best it can to stand like a person does. It was a really nice touch.

GREG: That’s why Neill set about making films like this: it sets up interesting questions. The whole thing is about can AI, a robot, a thing that we make, have a soul? Whatever a soul is supposed to be, a consciousness. Does it have rights? What does it mean to be human? That’s basically the question, right? The thing that is not a human, not a person, starts to cross to the uncanny valley and become a person. That’s the core of the whole film, I think.

CHRISTIAN: One of the real-world robots that Greg mentioned before is that Boston Dynamics Big Dog Robot. There’s something really biological looking about how it moves. In some of the videos, a scientist will give it a kick to show how quickly it can adapt to changes and physical input. But it makes you wince watching it because when someone kicks it, this slightly organic looking moving thing, you think it’s going to feel pain. You feel empathy for a thing that’s clearly, sort of, animal, but has no consciousness.

LERI: Yeah. The Big Dog doesn’t look at all like a real creature, but it’s all in that organic type of movement. So, I can only imagine Sharlto’s performance is going to be more empathetic.

GREG: I think it’s an appealing thing to all of us about robotics. It’s part of the feedback. This is why we love it. It’s not just to be a cool shape, but that they’re a representation of humanity, or what it is to be alive.

FLICKS: In this film, it’s a representation of a South African hip hop gangster, isn’t it?

GREG: Yeah [chuckles].

CHRISTIAN: That’s what makes it fun, for sure.

FLICKS: Apart from seeing the character brought to life in such a special way it was great to see how large a part Die Antwoord played. As actors, but also influencing production design.

GREG: A lot of this film was having to do with having them in this film, because of Antwoord and Neill both being from South Africa. I know, Die Antwoord, when they saw District 9, their jaws just dropped because they never thought in a million years that anybody from South Africa would have a worldwide reach like that. So, they just loved Neill to death. First as this kind of hero thing they have up on a pedestal, but as soon as they could get in contact with him, they did. They’ve become fast friends just because of that, being from the same sort of circumstances. So, it was just sort of a no-brainer that eventually they would hook up into a project and that’s how this particular one came about.