The thrillingly gory The Quarry blurs the line between video game and interactive movie

Highly bingeable teen horror experience The Quarry is chocked to the gills with scary movie tropes and conventions, offering a wildly visceral ride and a different approach to storytelling, writes Luke Buckmaster.

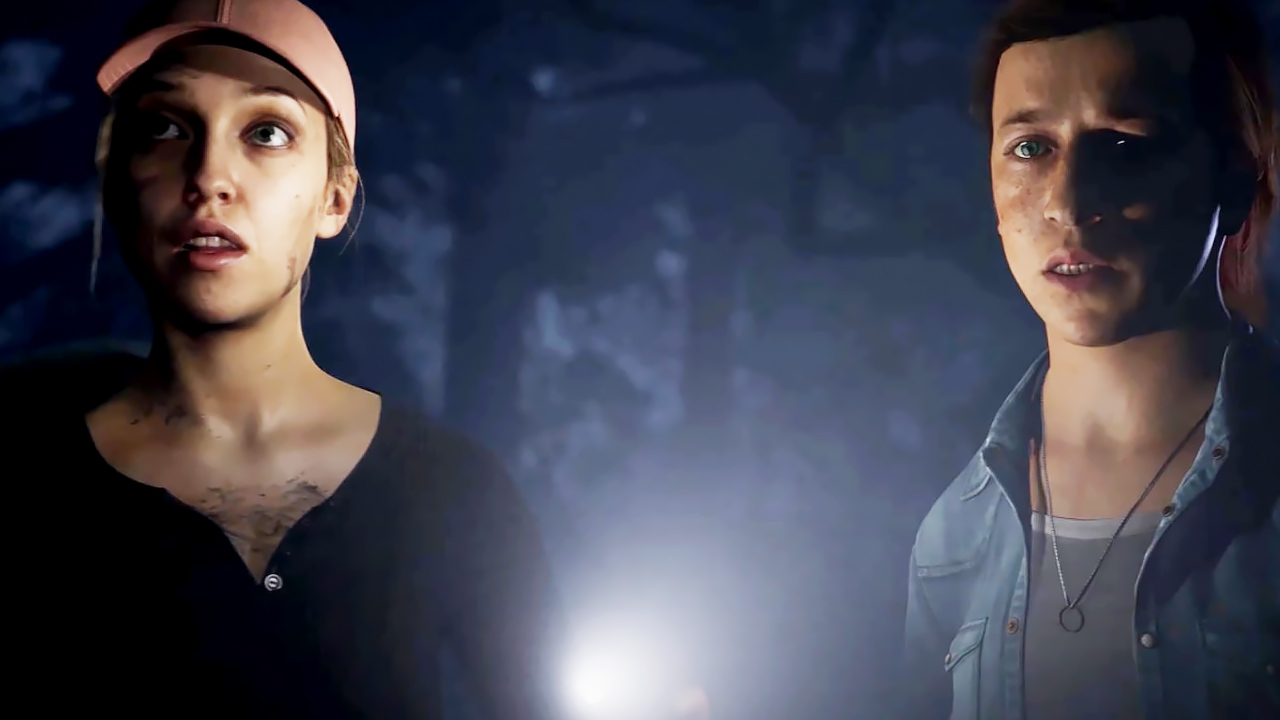

Horror fans with a passing or casual interest in gaming may find The Quarry the perfect gateway drug: it’s not merely inspired by, or indebted to, gruesome B-movies but is in effect one very long gore-splattered movie itself, larded with the tropes and lore of slasher flicks in particular. I say “in effect” because it’s debatable what kind of production this even is; the experience is marketed as a game, and is available on gaming platforms (Playstation, X-Box and PC), but is much more oriented towards the act of observing than playing.

It’s an interactive movie, in other words—a form of storytelling constantly in a state of flux, with no census on a precise format nor what it looks and feels like beyond obvious features i.e. selecting paths from branching narratives. If you enjoyed Black Mirror: Bandersnatch but left wanting something more involved than its basic Choose Your Own Adventure structure, consider The Quarry an absolute banger and a must-watch. Or a must-play. It kept me more engrossed than most horror movies (over a far longer running time—in the vicinity of 11 hours) and really got my blood pumping when it became clear the characters lie or die depending on your interactions.

The story mostly takes place over a single, splatter-filled night in a rural location where, of course, nobody gets any phone reception. It revolves around nine teenage summer camp counsellors who are all potential murder victims, and all potential survivors, depending on the choices made. Alternatively, decision making can be outsourced to the computer via a “Movie Mode”, which also comes with sub-choices: you can select a plot trajectory in which everybody dies, for instance, or everybody lives, or a “gorefest” to double down on the gnarly bits.

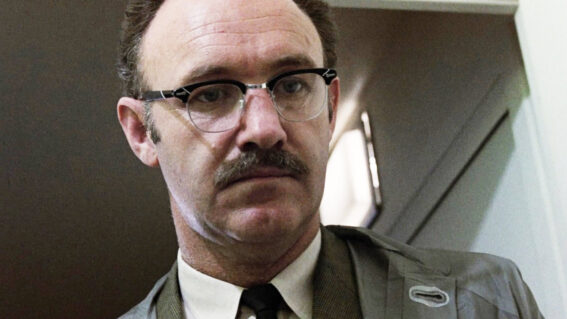

Characters include the sweet and arty Abigail (voice of Ariel Winter); the headstrong, straight-talking Kaitlyn (Brenda Song); a brooding hard-to-read type, Ryan (Justice Smith); the wisecracking Dylan (Miles Robbins); and requisite “hot chick” Emma (Halston Sage). Early in the story, after camp participants have left and the counsellors are preparing to do the same, its owner—Chris (David Arquette)—becomes unusually agitated when their car breaks down, effectively stranding them for one more night. Before leaving, he insists the group remain indoors and lock themselves inside—so of course they decide to make a bonfire and have an outdoors party.

Thus the ol’ “alone in the woods” plotline commences, except of course they aren’t really alone: there are locals including a mysterious old man named Jedediah (Lance Henriksen), and someone or something else, something more sinister, something that…I’ll stop there.

One of the first choices the player/viewer makes occurs during the prologue, when two characters are lost in a car on a full moon-lit evening. Do we attempt to get our bearings by consulting a leaflet or a map? The many decisions going forward can be, like this, as simple as selecting objects, in addition to choosing between basic actions (such as “run or attack” and “hide or attack”) and the emotional tone of conversational responses (such as “defensive or dismissive”, “impatient or worried”, and “aggressive or apologetic”). Some moments require the characters to be navigated through environments in third-person perspective; others the crude act of pressing a button as rapidly as possible.

In the original Scream, Neve Campbell’s protagonist famously observed a tendency for horror movie characters to run upstairs when they should be sprinting out the door. There are times when The Quarry avoids evoking this sort of “why did they do that” incredulousness by outsourcing decisions to the viewer, perhaps with an extra intellectual layer to muddy the process. For example, in one potentially dramatic scene, which might also be leading to a fake-out, Emma comments that she could open the trap door in the ceiling above, joking to herself that she might get mauled to death by whatever’s bumping around up there. The character is joking, but are the writers being serious? Is it a meta-bluff?

The script of The Quarry, like any multiform narrative, is a work of architecture in which the full picture can never be seen; only one chosen path. Breaking Bad creator Vince Gilligan described the writer’s room process as boiling down to two fundamental questions: “Where’s a character’s head at?” and “What happens next?” The Quarry invites the audience into this discussion, the act of choosing/interacting triggering a contemplation not just of immediate outcomes but the ripple effect they may have going forward—a different form of speculation (compared to traditional movies) for both content consumer and creator. The scope of the project is undeniably impressive; the developers claim the experience has 185 different endings.

I approached the experience cautiously, as someone who can get impatient during video game cutscenes, generally preferring story information to be divulged on the run through gameplay germane to the experience (such as scenes in GTA where you’re driving somewhere while having a narratively significant conversation with a passenger). That wasn’t the case during The Quarry. The cutscenes in fact are the moments of gameplay, in the sense that they’re small transitory segments the experience cuts to and away from. Towards the end in particular, I was on the edge of my seat—eyes bulging, brow furrowed, controller in hand, ready to bash the buttons furiously. At that point it left more like crack than a gateway drug.