Retrospective: the batty body horror of Death Becomes Her hasn’t aged a day

Despite receiving a tepid response when it arrived in 1992, Death Becomes Her became a beloved horror comedy that’s still a hit with audiences. Luke Buckmaster looks back at this deranged classic.

Robert Zemeckis’ funny, sassy, morbidly quirky Death Becomes Her is an enduring validation of what critic Andew Sarris described as the “hard lesson” of film history: that “the throwaway pictures often become the enduring classics whereas the noble projects often survive only as sure-fire cures for insomnia.”

I doubt anybody, when the film arrived in 1992, predicted that Meryl Streep and Goldie Hawn’s duded up, fountain of youth-chasing egomaniacs would still be lingering in the zeitgeist decades later, like a couple of old farts at a young person’s party: the latter with a hole in her stomach the size of a basketball and the former posing unique challenges to the profession of osteopathy. These two fruitcakes, fragile as porcelain mannequins, should befriend Samuel Jackson’s Mr Glass—who understands a thing or two about shatterable bones and the fallibility of the human body.

As Death Becomes Her’s many fans would know, Streep’s Madeline—a scheming narcissistic actor—and Hawn’s Helen—a scheming narcissistic author—consume a potion that keeps them young. The catch: they can’t escape their own bodies. That doesn’t sound like a deal-breaker, given all of us spend our existence confined to the same fleshy vessel. But it does mean that, while the pair have broken the spell of ageing, their bodies don’t magically replenish themselves: they are oddly and rather comically brittle.

When Madeline visits the sorceress-type dealer of said potion, Isabella Rossellini’s Lisle, on a dark and stormy night, William Castle style, she’s told to take good care of herself. That same evening, Madeline falls backwards down a large marble staircase, in an accident that would’ve killed her had she not imbibed the potion.

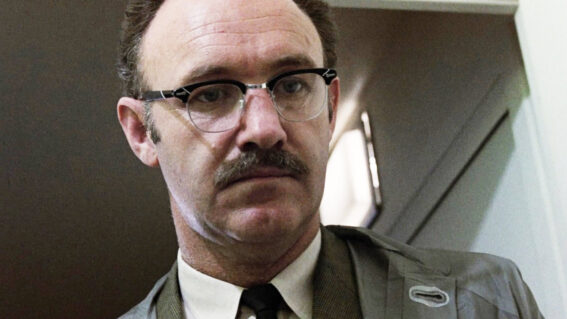

Ah well: at least her joyful youth-replenishing experience lasted for the car ride home. The fall that leaves Madeline hilariously disfigured—with a head facing backwards, positioned above her ass—is depicted on the film’s iconic poster, which does a fabulous job crystallizing the batty body humour embraced by Zemeckis and screenwriters Martin Donovan and David Koepp. Bruce Willis, who plays the pitiable Ernest—a plastic surgeon-cum-mortuary cosmetologist, who is Madeline’s husband and Helen’s ex-fiancé—stands next to her, one hand around her hip. The other clutches a multi-pronged candlestick holder, reaching through the space where Helen’s stomach should be. This poster brings two crucial scenes (capturing the women’s initial disfigurements) into one image, and correctly indicates a spectacle fusing special effects and the human body—performance with grotesquery.

The mood conjured by Zemeckis is midnight movie meets cartoon meets shrill melodrama meets showbiz satire. With tongue firming in cheek, the satirical elements and didactic messages flow through unencumbered by loftiness and pretension. The former takes aim at cosmetics culture in tinsel town, Streep once describing the film as “sort of a documentary on ageing in Los Angeles.” The latter tinkers on the edge of a “true beauty is within” sentiment (sans the potentially sermonish messaging) but is more interested in making cautionary points about ageing gracefully, and not mistaking a curse for a blessing. Ernest may be a wretched, lily-livered booze hound, but he’s the only character who cottons onto the idea that drinking a potion granting everlasting youth might be charting a fool’s errand.

The fountain of youth narrative is more than just deeply embedded in the zeitgeist: it reflects an ancient dream. One of the reasons Death Becomes Her still feels fresh, more than 30 years later, is the way it counters the dream of eternal consciousness with the curse of corporeality. French philosopher René Descartes famously separated mind and body, feeding the idea that one may exist without the other. This concept took hold in fiction, many narratives speculating about its dystopian or utopian possibilities—from the “brain in a vat” hypothesis (The Matrix, Avatar, Robocop) to the fantasy of transcendence (The Lawnmower Man, Transcendence, any film with heaven or hell in it).

Zemeckis et al go the other way, wrapping mind and body into an inseparable package. We are who we are: brain to bone, skin to soul. This simple, evergreen proposition helps explain Death Becomes Her’s staying power and continued cultural currency—including its subsequent status as a gay classic—even if the extent of its success remains a delicious mystery. It’s like the film itself drank the potion, and lived eternal.