Joker 2 is a box office flop. What’s next for comic book movies?

The financial failure of Joker: Folie à Deux is just the latest in a string of box office disappointments. The decline of comic book movies leaves Hollywood in a conundrum, writes Luke Buckmaster.

Pushing aside, for the moment, whether you like the film or hate it with the fire of a thousand burning suns, Joker: Folie à Deux is the rarest of tentpole releases—an example of the lunatics truly running the asylum. It’s wildly weird, takes big swings, and is as unconventional as they come: a highfalutin musical and courtroom drama in which we don’t even get to see the Joker being the Joker, let alone experience the thrills and spills synonymous with the superhero and supervillain genre.

The first movie—an origins story shaped like a Scorsese anti-hero narrative—was massively successful, grossing over a billion dollars at the box office and collecting 11 Oscar nominations. Exploitng that capital, director Todd Phillips and star Joaquin Phoenix appear to have been given cart blanche second time around. Phillips reportedly “wanted nothing to do with DC” and was allowed “to bypass any oversight from the brand’s gatekeepers.”

If we view the aforementioned asylum as an actual place, it is, in narrative terms, located in Arkham, Gotham City—prime real estate for blockbuster Hollywood franchises. Since Tim Burton opened the gates to Wayne Manor with 1989’s Batman, movies about the Dark Knight and his shadow-bathed universe have racked up billions upon billions. But now—holy smokes Batman!—Warner Bros executives are looking at box office receipts and thinking: shit.

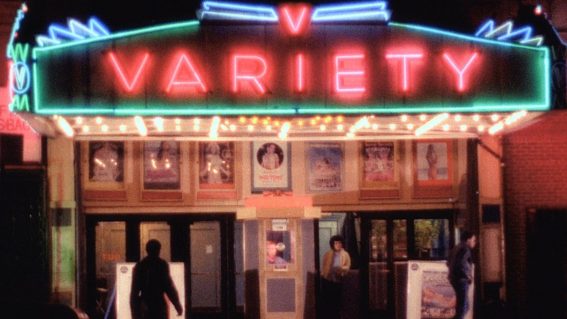

Folie à Deux has spectacularly bombed. According to a report on Variety, the film’s projected to earn around US$280 million, substantially below the amount needed to break even—which is around US$450 million (according to Variety) or US$375 million (according to Warner Bros.). Either way, in financial terms, it is—to quote Variety—”shaping up to be one of the year’s biggest catastrophes.”

Examining the entrails will hardly require great detective skills to figure out what went wrong. Asylums don’t function well if the inmates run them, at least in financial terms (although, I must say, I liked the film, describing it as “intellectually daring and unquestionably original”). The most interesting question is: what’s next for superhero and superhero-adjacent movies, which have long dominated 21st century cinema but are now in decline?

The term “superhero fatigue” has been making the rounds for a while, audiences understandably tiring of being fed the same content with only minor variations. Hollywood is well aware of this, with many recent blockbusters under-performing or outright flopping including Madame Web, The Marvels, Aquaman and the Lost Kingdom, Shazam! Fury of the Gods, The Flash, Blue Beetle and Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania.

While some big-earners appear here and there (such as Deadpool & Wolverine), the writing’s on the wall: studios can no longer rely on the same comic book cash cows they’ve been milking for many years. Or at the very least, they need to come up with different ways to milk them. Making comic book movies even bigger, with more bells and whistles, more bombast, and more special effects isn’t a viable option. Many of the aforementioned movies are as bright, loud and dumb as they come; god knows how studios would even manage to turn up the volume. Not that they can afford to; the budgets seem unsustainable. As Yeats famously wrote: “the centre cannot hold.”

Making smaller and edgier comic book movies isn’t a great option either. Partly because they’re unlikely to fill cinemas, and partly because this is terrain television has gained a strong reputation for, albeit in shows rather than movies, through well-made productions featuring long arcs and left-of-centre perspectives (i.e. The Penguin, The Boys and Watchmen). Streaming companies are also, generally speaking, better at recuperating losses, for various reasons including their subscription-based models, which rely on user growth and retention rather than the success of individual titles.

The conundrum facing Hollywood reminds me of a very different literary source than Yeats: the 1989 picture book We’re Going on a Bear Hunt. In it children famously chant: “We can’t go over it. We can’t go under it.” The solution, according to the kids, is simple: “We’ve got to go through it!”

And, indeed, Hollywood will go through it. If we assume the studios will scale back their investment in superhero movies, we can also assume they’ll rely as much as ever on well-known pre-existing IP (Barbie is a good example) in a bid to keep the “event” movie alive and well. Given how ingrained comic book movies are in the zeitgeist, it’s easy to forget that their rise to prominence—straight to the center of modern cultural experience—was spectacularly fast.

But nothing stays hot forever; the zeitgeist always moves on. The flopping of Joker: Folie à Deux—which, in hindsight, seemed destined for box office failure—is the least of Hollywood’s problems.