James Duval reflects on Gregg Araki’s The Doom Generation ahead of Sundance celebration

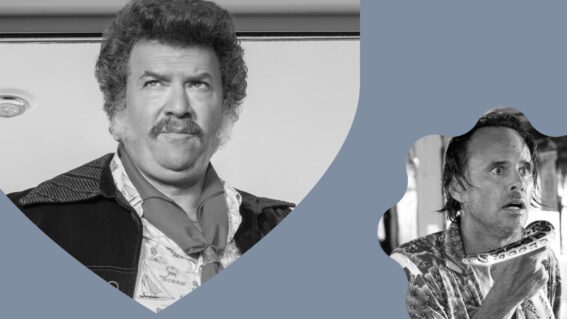

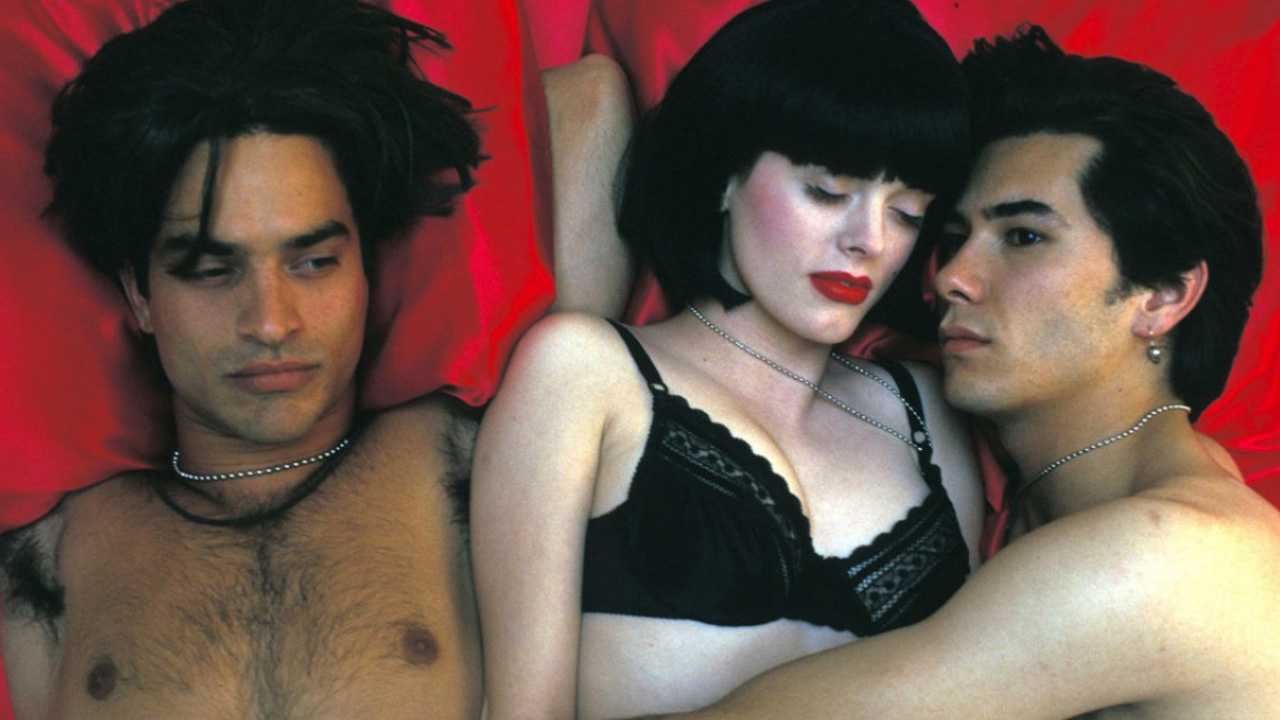

Starring James Duval, Johnathon Schaech and Rose McGowan (in her first lead role) Gregg Araki’s The Doom Generation is set to return to the big screen in its full apocalyptic and uncensored glory at next year’s Sundance Film Festival. Fresh from seeing Bones and All (and comparing it to Araki’s 1995 film) Cat Woods joined Duval for a chat reminiscing about The Doom Generation.

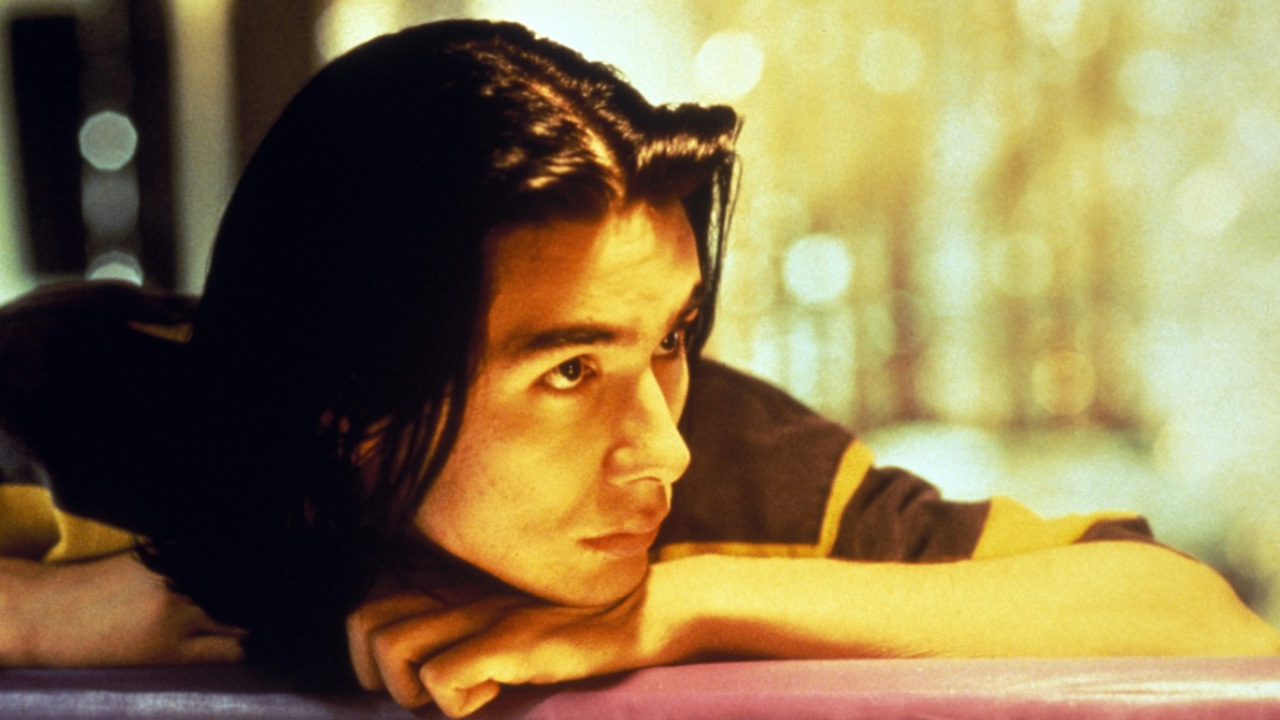

Detroit-born, Los Angeles-raised James Duval is the dark horse of indie cinema who has been notching up iconic films and unforgettable, awkward characters for more than two decades.

As Frank in Donnie Darko (2001), he donned a nightmarish rabbit costume and warned Donnie of the impending end of the world in 28 days. The Frank costume was donated to the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures this year, where it is now on display.

As memorable—and frankly, horrifying—as his role in Donnie Darko proved, it was his role as Jordan White in The Doom Generation that will be celebrated as part of Sundance Film Festival’s “The Collection” section in 2023.

Nearly three decades ago, Duval debuted in Gregg Araki’s movie trilogy entitled Teenage Apocalypse. His first outing was Andy in Totally Fucked Up, but it was arguably his long-haired, mumbling Jordan White in The Doom Generation that really cemented his grunge prince status. Alongside him, Rose McGowan played Amy Blue and Johnathon Schaech was Xavier Red.

“It was my fourth movie and my second lead. The first was with Gregg in Totally Fucked Up,” Duval recalls.

“I believe we’re releasing all three movies of the Teenage Apocalypse next year. From Jordan White in Doom Generation to Dark Smith in Nowhere, and Andy in Totally Fucked Up, there’s a running theme where—even though I’m different characters—it’s based on a coming-of-age.”

The Doom Generation, set in an apocalyptic, dark, ominous America full of roadhouse cafeterias, fried-food outlets, bottle stores and cheap hotels, debuted at Sundance Film Festival in 1995 in its uncut, uncensored glory. Next year, the same festival will screen the uncensored director’s cut, remastered in 4K.

Araki explained to Deadline that there are three versions of The Doom Generation:

“One is the edited version which was released in theatres and on video. The second is a ridiculous R-rated version made without my approval for Blockbuster Video, which has over 20 minutes chopped out and makes no sense (and I hope disappears forever after this re-release). The third is the version shown at the film’s world premiere at Sundance in 1995, which was subsequently censored per the distributor’s request…”

Duval recalls, “When it came out, the material was a bit much for people and Gregg knew it was as well, which was part of the trick. When we screened at Sundance, I remember thinking that it was so kind of nuts that I wasn’t sure if we’d get picked up for distribution. Samuel Goldwyn had picked up the film and asked Gregg to make a few cuts…it was something he’d never done before.”

Nine months later, Samuel Goldwyn asked for further cuts and when Araki “told them where they could stick it”, as Duval recalls, they sold the film to Trimark Pictures.

“When we got sold, we felt like they were trying to bury us, which I think they were,” Duval muses. “The upshot is, the fact that we’re sitting here talking about The Doom Generation 27 years later is really something.”

Alongside McGowan and Schaech, Duval’s White made up the trio of eccentric, confused outsiders seemingly on the run from either the law, neglectful homes, or just the boredom and predictability of ordinary life.

Duval is at home in Hollywood when we connect via Zoom. He has always looked younger than his years, he admits, and with his long dark hair and excitable expressions, he does still resemble the 21-year-old Duval of 1995. He is seated in a room of flamingo-pink walls and, surrounded by his various guitars, DVDs, books and collector toys, he is up for discussing everything from Araki to working as a busboy, American politics to the post-punk bands that we both still love (Depeche Mode, The Cure, The Smiths, Birthday Party and Bauhaus).

“What’s wild to me is that when we did the movie there’s certain elements that I identified with as a youth, but also growing up in the 90s, watching the [Berlin] Wall go down and seeing the Soviet Union dissolve, and watching the world come together for a moment became a very optimistic time towards the end of the decade. But, then everything changed globally in the 2000s. Everything comes full circle now, in the sense of the walls coming back up.”

He adds, “As you know, the movie is very dark in a lot of aspects, but there’s hope in the very end of it, and I think that exists in a lot of Gregg’s movies, like Mysterious Skin. In the middle of all that darkness there’s a spark of light or hope that shines through.”

Duval had met Araki in 1991, and since then, they’ve remained close friends in constant contact.

“I met Gregg in a café and you know, most of the actors—with the exception of Alan Boyce [Ian in Totally Fucked Up]—were all actors that Gregg had discovered in places he frequented: coffee houses, restaurants or ice cream shops. Rose was someone that the producer had seen and known from the gym, and asked her to come and audition for us.”

At the point McGowan auditioned, Duval and Schaech were already tight friends. Two actresses had pulled out of the production prior, including Jordan Ladd. Her mother, actress Cheryl Ladd, had read the script and immediately insisted her daughter have no part in it. Ladd went on to establish herself as a “scream queen” in—amongst others—Cabin Fever (2002), Club Dread (2004) and Tarantino’s Death Proof (2007).

Losing several actresses was not the only obstacle. Filming had been due to commence the same day that the 1994 Northridge earthquake occurred in California’s San Fernando Valley. Lights went out, buildings crumbled, and there was no access to fuel or groceries as Duval recalls.

Though he and Schaech drove to the set, nobody else showed up and they got back in the car to return home, only for their (pre-mobile phone) pagers to beep, calling them back to set.

“From that point on, it was six days a week filming for a month straight. After the first week, it was all nights. Even at that age, I was 21, it was a gruelling schedule of 12 hours a day, shooting in January in darkness.”

Duval recalls, “Johnathon and I hit it off right from the get-go. Johnathon and I really clicked. It wasn’t that I hadn’t clicked with Rose at first, but Johnathon had already been cast. I’d met Johnathon three months prior through an audition process. We didn’t mean to, but because Johnathon and I already knew each other, Rose felt like an outsider when she first came in.”

In a sense, that outsider status defined each of the characters. McGowan’s character had been neglected by her parents, White’s parents were equally inept, and Red was a mystery.

Duval based his backstory and understanding of Jordan White on their shared love for industrial, furious, post-punk music: “I grew up in Los Angeles, and I really related to the soundtrack. I was in high school in the 80s when my friends were into The Smiths, The Cure, and Depeche Mode.”

Duval explains that Araki’s scripts had scene descriptions that audiences would never know, referencing musical influences. His film titles and characters also reference musical Araki’s icons. The opening scene of Doom Generation features White in a goth-punk club in Los Angeles.

“Jordan’s slam dancing in this concert pit to this soundtrack from Nine Inch Nails, and it was Gregg’s dream to get Trent Reznor to score The Doom Generation. Thankfully, he ended up getting a song from him, Heresy, which is in the very beginning—‘God is dead, and no-one cares!’” sings Duval with a laugh. My character was a Trent Reznor fan, a huge Nine Inch Nails-head.”

Duval remembers, “When Gregg and I met, it was our love for music and the same bands—that was why we hit it off, straight off the bat. It was the music that let us into the characters and enabled us to identify with those characters.”

Duval pauses for a moment, then adds: “To be part of Gregg’s world, he saved my life. He gave me purpose, he gave me direction. I met Gregg when I was 18, right out of high school, and I hadn’t figured out what I was gonna do. Everybody I knew was moving off to college, and they knew what they were gonna do. Maybe I knew I wanted to be an actor but I’d chucked it out of my mind as something that wasn’t plausible.”

And yet, 27 years later, having freshly turned 50, Duval reflects on returning to Sundance to celebrate a film he feared may never even be seen beyond Sundance.

“Here’s the wild thing. I’ve never really given the movie much thought in terms of how people would react to it. It’s become a cult hit. I can see how it can still be pertinent in today’s society and how it can still speak to people. To be talking about it all these years later and for it to be playing at Sundance again, I’m beside myself.”