Interview: Dayna Goldfine and Dan Geller, directors of ‘The Galapagos Affair’

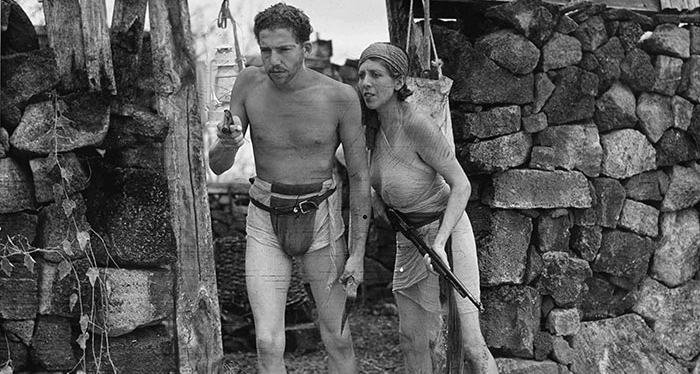

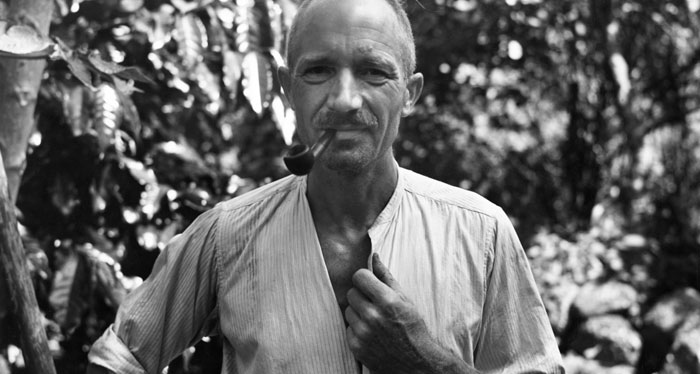

The Galapagos Affair: Satan Came to Eden is a true-crime documentary that explores the curious goings-on when a Berlin doctor and his mistress dropped out of society and resettled in the Galapagos Islands in the 1930s. Followed by others, soon an experimental, free-love society flourished – until some of the new arrivals disappeared and allegations of murder began to swirl in the air. Filmmakers Dayna Goldfine and Dan Geller (Ballets Russes) delve into what took place by assembling archival footage, modern testimony, and utilising voice talent including Cate Blanchett, Diane Kruger and Connie Nielsen.

We were lucky enough to chat to Dayna Goldfine and Dan Geller about their film, which has spent many, many years in the making.

FLICKS: I’ve got a theory: because New Zealand is a pretty young country in terms of European settlement, the idea of just running away to a beach, an island, or somewhere where there’s no people around may not seem as weird. But for a couple of Germans…

DAYNA GOLDFINE: It’s interesting, because I just got done reading The Luminaries. I was thinking about it, because the people that went to New Zealand in the 1850s or whatever, were trying to start a new life. They definitely were leaving things behind and they weren’t coming because they were prisoners, like the Australians. On the other hand, when they came here they knew they weren’t leaving society. They were coming knowing that there were at least people here, and the people in the Galapagos, at least the ones in our story, they were fleeing society and trying to be as misanthropic as possible, whereas I think perhaps the people who came here, at least the ones who are described in The Luminaries, were coming, not so much to get away from all society, but to start completely fresh.

DANIEL GELLER: The Galapaganians that we’re talking about had no interest in any kind of economic system. They wanted to leave it all behind. And when you think about Germany, inter-war Germany especially, with the depression full-on, with the country bombed to pieces, and with another war looming, that the last thing they wanted to do was participate in any kind of organised civil and economic group. Money has found its way there now. But the early arrivals prided themselves on being able to live off the land, and not getting caught up in monetary needs.

I found it quite interesting that you’d travel to the Galapagos, a place that has played such a crucial role in science and in our understanding of who we are, yet reject all of those notions of modernity.

DANIEL: Right. It is that, and yet they were going there with almost no interest in that Darwin lineage. It didn’t even register, and truthfully, for most of the people who came to this island in the early to mid-twentieth century, including some of the moderns, as we call them in the movie, with few exceptions, there were a few, they didn’t care about that role that Galapagos plays in the science of humanity – the major leap forward in understanding evolution and natural selection. Did not care. It wasn’t about that. It was just about getting away from the world, being self-reliant, controlling your own destiny. And we asked several of them that. Didn’t factor. It wasn’t interesting to them.

DAYNA: One of the themes that kept recurring when we would talk to people was, almost everyone changed their entire life because of a book they read, and I’m not sure how many people today would do that. But it wasn’t Darwin’s book; it was Leveque’s book, and he may or may not have talked about Darwin, but he really talks about it as the end of the world, and one of the last bastions where you can leave society. Another of the families left because of a different book that they read, that had a chapter about the Galapagos. Over again and again we would run across these people who read something that was just lodged in the back of their brain and made them take a really extreme action. I don’t know if that would happen today.

In a way you’d kind of like to think so.

DAYNA: I would love to think so.

It’s also a terrifying prospect at the same time.

DAYNA: I know. And where would one go, anyway? There is no undiscovered country, really.

Is that part of the appeal of telling the story, for you guys? That it’s not that long ago, but it’s such a bygone era – where could you escape to now?

DANIEL: We all have that impulse, really, whether it’s in good times or bad, more often in bad times, of saying, “Oh fuck it all, I just want to leave the world behind, and go to a quiet, deserted island”. That impulse is there, because it’s hard to get along in society.

DAYNA: We were asked to go to the islands in 1998. Dan was doing camera work and I was doing sound on another Darwin project. You really do get this sense when you set foot on them, that, “Oh, this how it all started – and if I look hard enough, and long enough, and am patient enough, I can almost see evolution happening”. It’s so cool.

Is this the story that you uncovered over time, after your first visit to the Galapagos, or is it something that people talk about over a whisky quite readily? How sort of folklore-y is it?

DANIEL: The preponderance of people who are on the island now are Ecuadorians, [and] when the tourism industry really began to explode in the late ’80s into the 1990s and beyond, that’s when Ecuadorians came to support the tourist trade. There was not much in terms of an economic life in Galapagos until that happened. So they heard bits and pieces of the story. It’s not particularly well-known. And we showed the movie there at the end of May. We were brought down there by an arts and cultural organisation and people were utterly amazed. The theatre was packed. It was only in bits and pieces that they’d heard parts of the story, and this was the first real attempt to learn it all and they were fascinated by it. The old-timers, some were more interested in talking about it than others. Some had a good time joking about the insanity of it all.

DAYNA: A lot of them grew up hearing those story-type things. Teppy Angermeyer [in the film] says, as a child, hearing about this kind of stuff, it was really scary because there weren’t a lot of deaths here, but he grew up sitting around the Galapagos version of a campfire, hearing his father and his uncles, regaling them with these preposterous ghost stories about what happened in the paradise, but as a kid you had to start believing it.

DANIEL: But in terms of discovering it, having read Margaret’s book and then I remember we got a copy of Dora’s book, and reading the two and realising, “Wait a second, these two accounts of what happened in these disappearances don’t line up at all, and in fact each insinuates that the other is responsible”. We thought, “Well, now we’ve got the basis of something really sparkling and fun as drama,” and then the question was – until we found our film footage – how would we tell the story? And then all the elements were in place for us to start making a movie. So, in that sense, we discovered it bit-by-bit. The two books were really important, because that’s where the deeper story gets told. Just by reading a synopsis, it’s hard to understand what’s happening, but by reading the first-person accounts, in very different prose styles as well…

How long did you end up spending on those islands, and what was the gestation period of getting from ‘basis of a story’ to ‘story of the film’?

DANIEL: All [together] we probably spent four to six months in the islands, but the piecing it together as a script and in the editing room, we were doing that simultaneously where we were looking at these sources and articles that Dr Ritter had written, newspaper accounts, and really synthesising a mass of other writings.

DAYNA: Well actually, we went in ’98, became obsessed by the story, read this 12-page chapter in this book about the history of the islands and the human story. [Then we] spent the next part of those two weeks on the boat, going back and forth about what had happened.

It’s so tempting to delve into, right?

DAYNA: Oh, it was so much fun. And there was humour in it, too.

DANIEL: Morbid.