Interview: Creation Records’ Alan McGee on Oasis Doco ‘Supersonic’

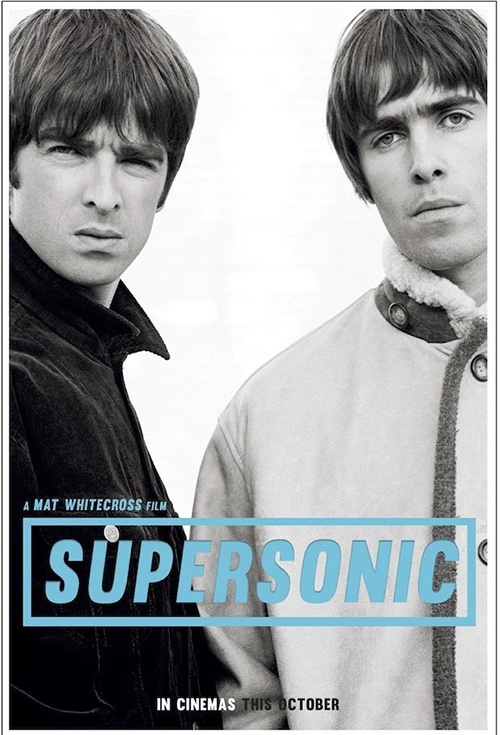

As Oasis documentary Supersonic arrives on home video – perfect for having a few beers in front of with your mates – we jumped at the chance to speak with musical maverick Alan McGee.

Once Creation Records head, and now back working with some of his former acts as Creation Management, McGee worked with a litany of legends including The Jesus and Mary Chain (who, he’s announced, have a new record out next year), Primal Scream, Ride, Teenage Fanclub and many more.

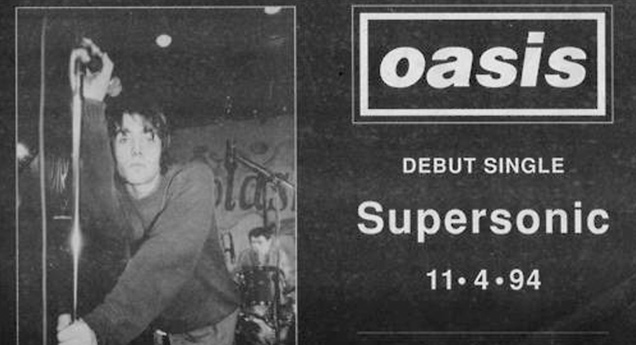

And then he signed a little band with two loudmouth brothers that went on to conquer a fair whack of the world…

FLICKS: Have you enjoyed seeing the reaction that the film’s been getting as people have had the chance to see it?

ALAN McGEE: Yeah, yeah. It’s been great. It’s amazing meeting people who remember how great a band Oasis were, which is kind of amazing for everybody. Amazing for me, but amazing for the Gallaghers, and amazing for everybody involved in it.

It must be so bloody long ago in a way – well in most ways – right?

It’s only 20 years. I’m 56, so it’s not that long ago [laughter].

I guess the theory can be that times like this breed very interesting art, particularly in the context of austerity and things like that. What do you reckon might be going on in the estates over there that we’re not aware of at the moment?

I don’t know. I mean, I think it’s that everybody’s near the edge. Everybody’s living on their credit cards. It’s like it’s edgy. I was lucky because I came into music in the 80s, when people bought records – in the 80s and the 90s.

I loved how much handy-cam footage is in ‘Supersonic’. With phones now, you expect content to go online immediately. Back then, those guys wouldn’t have expected people to be watching that footage – except for friends and family, maybe. Do you think the goofing around was ever intended to be seen?

No. I don’t think it ever was.

Do you expect then, there was there quite a lot of rubbish to wade through?

I don’t call it rubbish. I just think of it probably it was a lot of home footage that just people found in bits and pieces, and they got it together from there. I kind of think there was probably a lot of stuff, I would imagine, and I didn’t make the film. But it was pre-internet and pre-people with phone cameras and stuff like that. And I imagine it was slightly difficult too.

I guess there’s something to be said for how that can make a band more of a phenomenon though, right? Because it’s not matter of fans having constant access to them.

Yeah. I mean, I think the initial Oasis from about ’91 to ’95 was just a band of kind of mates really. Do you know what I mean? And then post that, we started bringing in session players like Alan White, and then Andy Bell and Gem. But these guys were really just session players.

Thinking about how much of a media presence the Gallaghers have enjoyed the whole time, it’s a great reminder of the kind of shitstorm that they did create around themselves while it was a band with the world in the palm of its hand. Because I think for many people – and younger audiences – you might kind of grow up with Noel just being a familiar guy that pops up in music documentaries.

Yeah. It’s like they were just unreconstructed. They just did what they did, and people bought into it. But they were very unreconstructed.

How happy were you about the time period that the film’s set over, because it does feel like it celebrates the most positive aspects.

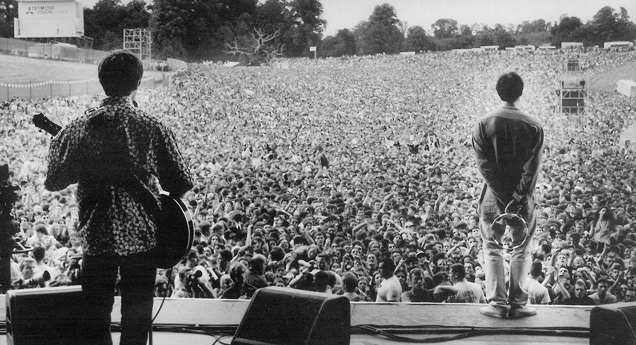

I think it’s fine. Again, it was obviously the producers’ take. They wanted to make it euphoric. They’re about to shoot a film next year called Creation Stories, which is probably going up to about ’99, and it’s going to cover Creation, Oasis, all the different other things. Irvine Welsh is going to write that script. And that might be another take on the whole 90s time, because that’s off of the book that I did [Creation Stories – Riots, Raves and Running a Label]. But yeah, the Oasis documentary goes up to Knebworth. Kind of what the primary thing is, the band should’ve ended at Knebworth.

What’s your recollection of that period, when the documentary finishes? And how would you have approached things differently, if you had the opportunity?

I think it’s really difficult, because I don’t make films really. I might be involved with a few films, like the film that’s coming out about Creation, about my book, but the truth is, even then they are stopping around ’99. I think it’s kind of like, how could you really tell the Oasis story up to 2009 – over 17 years in two or three hours? I mean, it’d have been a five-hour film!

Would you have done anything differently from a personal point of view?

There’s not a part I would like to do differently. I’m friends with both Gallaghers. It’s probably why I’m on the phone to you. But I probably, personally… Knebworth would have been an amazing time for everybody to stop doing it. But you know what? It’s fine. If things happened the way they happened, and everybody went through an experience through Oasis, then it was fantastic. And equally, the decline would be fascinating as well. But it’s just the timing – a time capture thing of like 17 or 18 years of music in two hours? I don’t know if anybody could do that. You know what I mean? Not in any substantial way.

Going back to what’s going on in the UK at present. How hard would it be right now for a band to unify an audience – or not necessarily a rock band but any musical act?

I just think very hard, because maybe somebody will come along and do it. But I think it’s practically impossible. I think music is so niche, because you’re not up against another rock band anymore. You’re up against Instagram, Facebook, Spotify, YouTube [laughter]. You’re up against completely other things.

At the discussion I was at earlier tonight, the artist Lawrence Arabia half-jokingly laid the blame for the decaying of attention and spending on music at the foot of restaurants and craft beers. And so that’s taken everyone’s attention away from music.

Who did you lay the blame at? Whose fault was it?

Restaurants, fancy food and craft beer. So taking people’s attention away from music.

[laughter] I don’t think that’s actually the problem.

When was the last time you went to the pub instead of buying a record Alan?

I don’t drink. So probably years ago.

What are the sort of subcultures and things that you see happening musically in the UK, that are exciting at the moment?

I would think it’s very niche, but people are into what they’re into. I manage bands now. I do Creation Management and manage The Jesus and Mary Chain, Happy Mondays, Black Grape, Cast, Willow Robinson, Alias Kid. And then you hear of an artist that wants you to manage them. You’ve never heard of them. And you look, and they’ve got 500,000 fans on Instagram [laughter]. The music is so niche.

Does that remind you of when your first sort of fandom for music came about then? Because I’d imagine many things that interested you when you were younger weren’t exactly popular.

We’re living in the digital age. It’s completely different. I don’t know if I’m a great commentator on the digital age, because I’m just part of it. But I don’t know if I have a great vision of anything. If anything, it’s isolated people from each other, which I don’t think’s good. But there you go.

I guess that’s the opposite of huge unifying acts, which is what we’re talking about with Oasis.

Yeah, I know. But it’s so hard for that to happen. I don’t know if that can happen again. Maybe One Direction. Maybe One Direction was a unifying act. I think they’re fucking lame unfortunately. Do you know what? That’s a good point. I think One Direction were the last big worldwide act, that came through. What do you think?

Yeah, maybe. Not for me. But who am I to judge?

No. I don’t mean I like them. I’m just… you asked me a question; what was a unifying act? And I’m just thinking, actually; what band broke worldwide everywhere? Probably One Direction. Do you know what I mean? Which just says it’s going to be very hard for rock and roll bands to ever break again.

I never saw Oasis live. So I’m not the person to judge the merits of the show. But it seems like they might have been the apex of a gang of guys, not doing heaps on stage, with an incredibly huge audience in front of them.

These early gigs were amazing. Maybe there’s something quite ritualistic about live gigs. It goes right back to stone age man.

Without that possibility of becoming a world-conquering act, do you think it makes kids less enthused to pick up the drums, pick up a guitar and want to be a rock star?

I think people… I think you still get kids who want to be rock stars. I just think it’s probably more difficult, because there’s so many other distractions for kids. As I said, with Instagram, Spotify, YouTube, Facebook, it’s just there’s so many other things to distract kids away from playing an instrument. But you know, we’re still going to get rock stars. You’re always going to have people that want to be rock and roll stars, and hopefully that film will remind them, what being in a great band could be like.

It’s got so many of the fairy tale qualities of what you’d want your own journey to be like if you’re in that position. Do you think that’s one of the things that was so attractive about Oasis, that it was a meteoric rise, and you were on their side throughout?

Yeah. It was a dream. It was a dream thing that came true. It was like, I can remember sitting with a manager, Marcus Russell, saying if we did all this, then – if we can do this by that time – we’d be doing well. And I remember about six months in, it managed to tick all the boxes. And after that, we’re in no-man’s land. We didn’t know where it was going. And it just kept going. It just kept getting fucking bigger.

When did you first start getting the feeling that things were getting a bit difficult with the band – that it was getting a bit rocky?

It always was [laughter], from day one. So probably from the minute from about 1995 onwards, 1996, when they got big, then there was money and ego, got involved in it all.

Does a bit of human nature kick in as well? Like, if an artist has so many people on their side and they’re in their corner, do they kind of want to maybe fuck things up for themselves a bit?

I don’t know really. I don’t think Noel’s like that. Maybe Liam’s a little bit like that sometimes. But I think they both embrace success. They both liked being huge and megastars.

Obviously it’s happened forever for you, but how many demos were starting to land on your desk weekly as Oasis got huge?

I don’t know. Probably about 100 a day at that point. Yeah. Creation was crazy. But we already had that trendy thing. We were pretty big anyway. Then Oasis just made us probably one of the biggest indies ever out of Britain – maybe the biggest. We probably were the biggest indie ever. I don’t know. I’ve never really thought about it, but maybe we were.

How does the Creation catalogue still perform today? Are people still buying it?

No idea. I sold it to Sony in 1999 for 30 million, so I have no idea [laughter]. I don’t care really.

Before we wrap up, Alan, are there any other Creation bands that you think there should be a movie of? I’d see a Primal Scream doco in a heartbeat. Who else do you think would be worth given the same treatment that the Gallaghers had in ‘Supersonic’?

I think with a documentary, it’d be amazing if we did a Primal Scream one. Although they kind of did one for Screamadelica, but one about their whole career would be fantastic. The Jesus and Mary Chain would be fantastic. A few bands like that around that you would love to know the full story. Happy Mondays would be good as well.

Read our four star review of ‘Supersonic’ or find out how to buy it.