I Kid You Not: The Prince of Egypt might be cinema’s last great Biblical epic

Who said family films aren’t cinema? In his column I Kid You Not, Liam Maguren critically evaluates the excellence in kids flicks and writes them into the history books. Turning 25 this year, Liam celebrates DreamWorks Animation’s somewhat forgotten Biblical epic The Prince of Egypt.

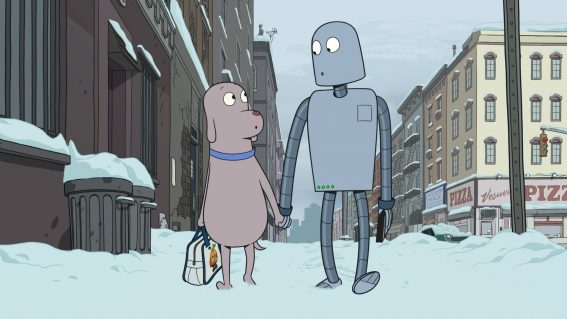

The Prince of Egypt

Modern-day faith-based films are having a moment. There are the Ned Flanders of the group—harmless, mid-budget, well-to-do films like 2016’s Risen or 2018’s I Can Only Imagine. Then you’ve got the slightly unhinged suburban neighbours screaming, “God’s not dead and Heaven is for real,” like 2014’s God’s Not Dead and Heaven is for Real, which feel less like faith-based work and more like faith-panic comfort food made to siphon money off a certain upper-middle-class demographic.

I should spare a thought for Darren Aronofsky’s fantastically nutty Biblical flicks—the most recent being 2017’s mother!—which are more akin to a homeless man holding an End is Nigh sign.

Decades prior, faith-based films were prestigious Hollywood productions. Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ, four-hour epic The Greatest Story Ever Told, and 1956’s The Ten Commandments were all big-budget, Oscar-nominated retellings suited to the nines. Good luck trying to get a kid to sit through them, though, or anything from the wave of low-budget animated Christian mush that plagues the video rental and streaming market.

Delivering a version of Exodus that was both epic in scale and suitable for the whole family, DreamWorks Animation’s The Prince of Egypt achieved the miraculous. The most expensive animated movie ever made at the time, it might just be cinema’s last great Biblical epic.

The film makes its grand ambitions known right from the start, opening with the colossal musical number Deliver Us. Composed by Stephen Schwartz (who won an Oscar for the film’s climactic track When You Believe), the orchestral muscle and skin-chilling choir in Deliver Us lays the groundwork for the entire score made in collaboration with Hans Zimmer. Emotional and grandiose, the music perfectly accommodates a time and place where Egyptian royalty and the structures dedicated to them loomed large, as did the strife of the slaves who built them.

The sights of whipped backs and implied baby murder are just two of the many surprisingly uncompromising moments in The Prince of Egypt, despite the story being widely known. It’s a bold move for a film hoping to capture a family audience, but an understandable one—slavery isn’t a subject that shouldn’t be watered down or hidden away. Crucially, The Prince of Egypt makes the story’s more horrific details palpable through music, montage, and tasteful cutaways (you don’t actually see a baby getting murdered).

It’s also surprising that, for a faith-based film, it doesn’t dwell much on the “faith” part. Directors Brenda Chapman, Steve Hickner, and Simon Wells instead apply their focus to the story’s core relationship—Rameses, the future ruler of Egypt, and his adopted brother Moses, who eventually learns of his Hebrew heritage—a tight brotherhood tested to a heart-breaking end.

Their story holds plenty of relevance today. For Moses, understanding his roots leads him to realise the suffering caused for the benefit of the dominating class. Choosing a more valuable life as a humble shepherd (he literally sheds his wealth to get there), God eventually puts him on a path to free the slaves.

To rephrase that using the parlance of our times, Moses got woke and became a social justice warrior.

By contrast, Rameses could be a stock-standard villain to Moses’ God-chosen saviour. However, The Prince of Egypt wisely illustrates the future Pharaoh as a man crippled by fear of failing a family legacy. Despite showing an ability to display genuine affection, especially towards his adopted brother, the inner turmoil instilled in him by his dominating father blinds Rameses’ heart. There are some tremendously composed visual reminders of Rameses’ moral cage, built with the towers of expectation and fastened by the many privileges gained through inherited wealth.

More importantly, the performances power these characters’ turning points. Not the performances from the voice actors, who do a fine job for the most part, but the performances by the animators, who cast an impeccable eye for detail for the most nuanced of facial expressions. The slow movement of the brow and the short quiver of the lips do a lot to humanise Rameses, which makes his decision to defy Moses—and the increasing plagues on his city—all the more difficult to bear.

The Prince of Egypt doesn’t just deliver on the small details; it relishes in spectacle, too. Namely, the four-minute parting of the seas sequence, which reportedly took ten animators two years to accomplish and still induces moments of awe, from the tightly framed gushing of the sea waves to the silhouette of a whale gliding along the ocean wall.

Back in 1998, audiences were clamouring for the freshness of 3D animation, but not a single frame of Pixar’s A Bug’s Life or DreamWorks’ own Antz holds up as strongly as the traditional animation seen in The Prince of Egypt. Even its employed 3D elements hold strong for the most part, especially the pre-Lord of the Rings tactic of using CGI to fill out a gigantic crowd scene.

And yet, 25 years later, The Prince of Egypt appears to have been lost to the sands of time—not fully buried but dusted like a forgotten relic. Why is that?

For one, whoever markets the film today doesn’t seem to know how to market it. A recent Blu-ray release of the film comes with a painfully generic cover hiding any sense of scale portrayed in the film. There’s only one critic quote on the back that says, “wonderfully entertaining,”—a woefully undersold description that seems directly targeted at grandparents wandering the supermarket who forgot to get little Jimmy a birthday gift.

There’s also the inescapable fact that it’s a faith-based film, a term that sends a quake up the spines of non-Christians. Which is unfortunate, given the pertinent social themes at play and how well the film tells its story without ever feeling like it’s waving a Jesus Can Save You flyer in your face.

Additionally, its respectable gross at the box office didn’t come close to earning the big Disney bucks. And critical reception was favourable with the almighty Roger Ebert calling it, “a film that shows animation growing up and embracing more complex themes, instead of chaining itself in the category of children’s entertainment.” However, that attempt at growth and complexity didn’t work for everyone, with Time magazine stating, “The film lacks creative exuberance, any side pockets of joy.”

I personally wouldn’t go so far as to call it a masterpiece. Some of the voice work feels miscast (Jeff Goldblum stands out in the wrong way), the cartoonish animal designs feel tonally out of place, and the jovial spirit that made Moses so likeable at the start of the film deflates towards the third act.

However, those setbacks fall under the shadow of The Prince of Egypt’s admirable ambitions and many successes. It not only holds an Academy Award, but it also marks Chapman as the first woman to co-direct an animated blockbuster. Kudos also goes to getting the ethnicity of the characters correct, which may sound a little trite given the heavily white voice cast, but given how Ridley Scott fully whitewashed the characters with his dull 2014 version Exodus: Gods and Kings, it’s certainly noteworthy.

So is it cinema’s last great Biblical epic? Some might bat for Aronofsky’s Noah or Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ, despite the flood of contention and controversy plaguing both of those films (for completely different reasons). Any other worthwhile, post-1998 faith-based films probably don’t have the budget or production heft to be considered “epic.”

Perhaps it doesn’t matter if it was the last great Biblical epic. At the very least, The Prince of Egypt should be considered and remembered for simply being a great Biblical epic—one that runs under 100 minutes.