Why Robot Dreams is my favourite film from 2024

Who would’ve thought that one of the best films of the year would be a silent animation exploring the love between a robot and a dog? A smitten Luke Buckmaster unpacks the beauty of Robot Dreams. This piece was originally published on July 30, 2024.

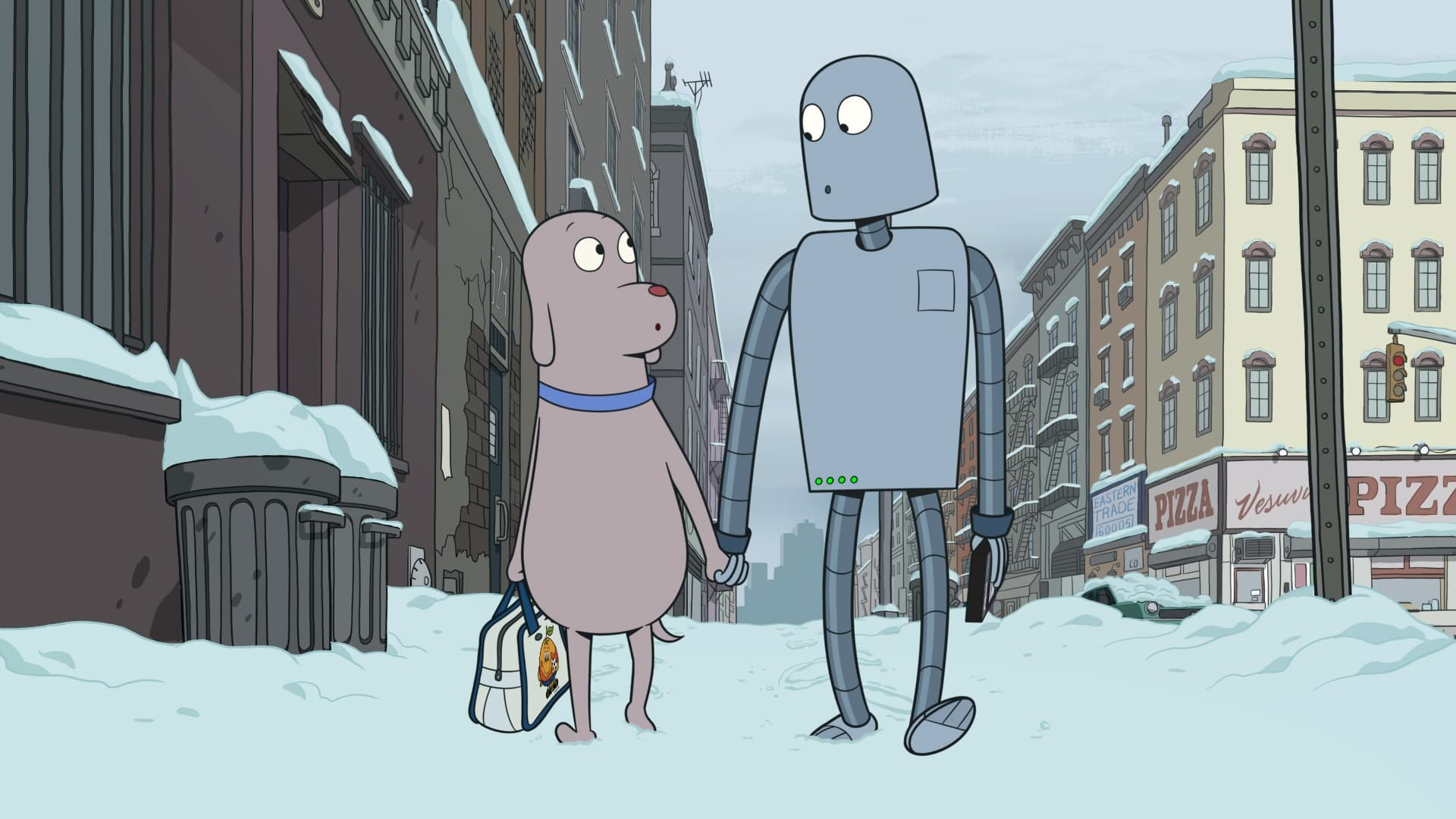

Androids don’t just dream of electric sheep in Spanish filmmaker Pablo Berger’s wonderfully bittersweet animated movie: they think, feel, long and love. And like humans they’re cursed to the confines of a body. Set in a bizarro Bojackian version of Manhattan circa the 1980s—before the age of AI—the lead robot, billed simply as “Robot,” cannot upload itself to the cloud. When it gets rusted and stuck to the sand at a beach, too heavy to be lifted, it passes the time by fantasising about various ways it could return home to its new bestie, a dog billed as “Dog.” We see its yearnings visualised and recognise them as the titular dreams.

It took me a while to catch up with this film, which premiered last year on the festival circuit but was released theatrically in 2024, and has been available to stream for a while. I’m so glad I did: it’s a richly emotional experience told with a daydreamy charm that never seems to work hard for our affections. Scene by scene it’s modest and unprepossessing—nothing remotely innovative or boundary-pushing—but as a complete package Robot Dreams feels zesty and original; I struggle to think of any titles to name drop that offer comparable experiences. The same is true of Berger’s feverishly weird, wild and strikingly stylized 2012 production Blancanieves, which transports the story of Snow White to the bullfighting arena of 1920’s Spain.

Like Blancanieves, Robot Dreams (loosely based on a graphic novel by Sarah Varo) is a silent production—and it doesn’t cheat. When Dog watches TV early in the runtime, flicking between stations, we hear ambient noise rather than voices from the television. Looking into a neighbour’s apartment and seeing lovers canoodling on the couch, we instantly understand that Dog is lonely and in the market for companionship; like in great silent pictures there’s a condensed, evocative efficiency in this film’s images. Dog orders a robot pal, who looks a little like the Tin Man, but has no absence of a heart: if anything his emotional range is painfully large, the aforementioned beaching leaving him stranded and forlorn.

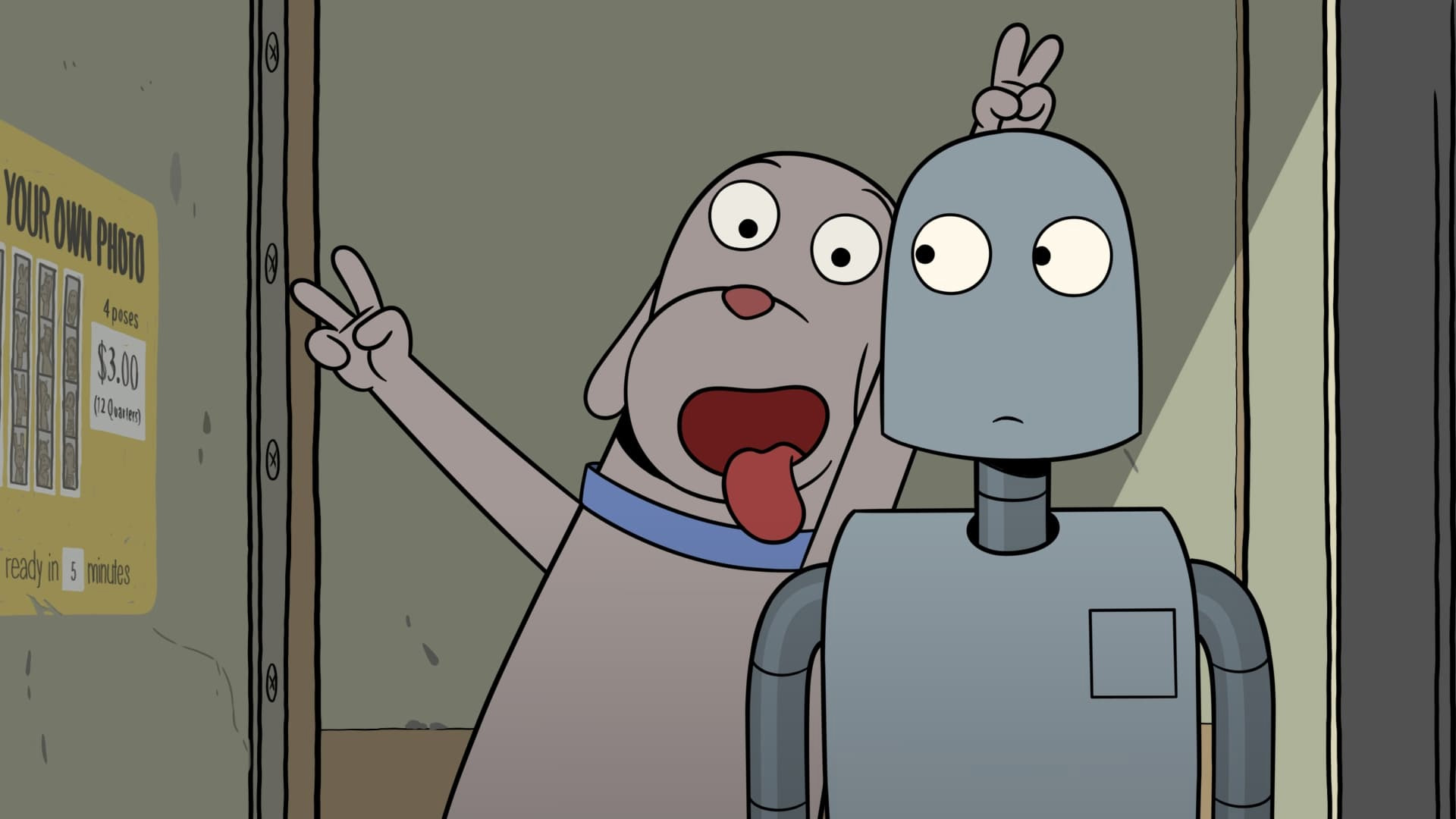

Soon after Robot arrives, the pair hit the town and the film becomes an all-out ode to cosmopolitan living: the sights, sounds and pleasures that can only come from congested community spaces bringing together the bored and the busy; the order and the chaos of the city. We observe buskers (including an octopus bucket drummer in the subway) and follow Robot and Dog to a park, where they dance on roller skates and purchase hotdogs from a street vendor. These events are commonplace, in real life as well as the movies, but the animation and animal-oriented world etches out a space between familiar and foreign: common things through fresh eyes. The Big Apple—which is specifically New York, but could represent any city—is seen as a place of infinite possibility.

The opening act has no cynicism, nor any inclination to intellectualize or moralize. It seems content to exist in and relish the moment, drawing on the uncertain beauty of early romance, a time when big connotations are drawn from small events—smiles being exchanged, hands being held. The film’s second half conjures more complex emotional gradients, which don’t need to be unpacked in detail here; best to hit play and let the film work its charms.

The relationship between the lead characters has an anthem: the melody of Earth, Wind & Fire’s disco classic September, which has been deployed in countless movies and shows but has surely never been used better or more memorably than here. Music is important but Robot Dreams is an ode to the sheer visuality of the cinematic medium. Entirely dialogue-free movies have always been rarities, even in the silent era, when films often featured lots of talking, displayed via intertitles (consult F. W. Murnau’s 1924 masterpiece The Last Laugh, about a hotel doorman crushed by the system, for a great example of a truly wordless movie, belonging to a German film movement called Kammerspielfilm).

A medium dominated by talking was not a historical inevitability—just one of many path’s cinema could’ve gone down. And not necessarily the best, as Robot Dreams reminds us. It’s fuller and richer than the vast majority of productions released during this or any other year: silent in terms of dialogue, but noisy with emotion.