Retrospective: get back to Yellow Submarine, the Beatles’ tripped-out animated classic

With Peter Jackson’s Beatles doco series Get Back landing on Disney+, now’s a good time to revisit the blockbuster band’s tripped-out 1968 classic.

The Beatles continue to prove material ripe for documentary picking. Attracting A-list directors including Martin Scorsese and Ron Howard, films hoping to investigate The Beatles’ astronomical success are guaranteed box office hits. The latest filmmaker to take on the Fab Four is Peter Jackson, focusing on the recording of the 1970 album Let It Be and their rooftop concert on the roof of Apple Corps in Savile Row across his three-part Disney+ series The Beatles: Get Back.

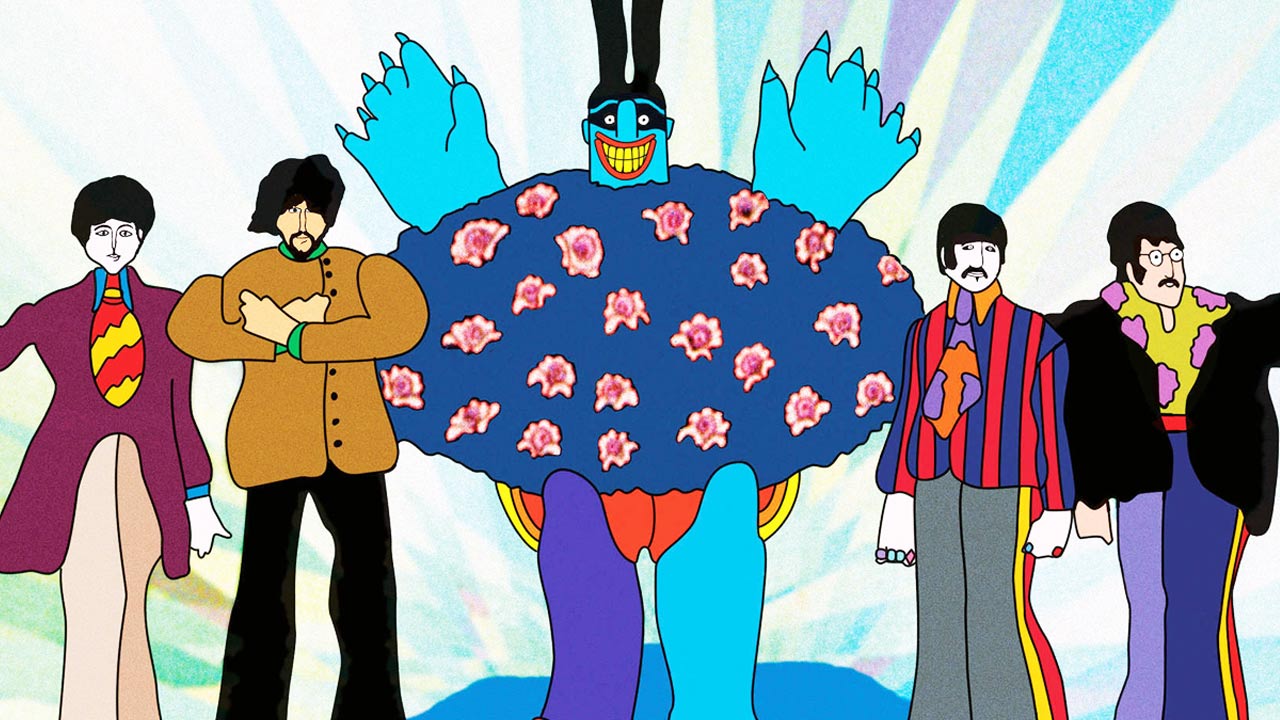

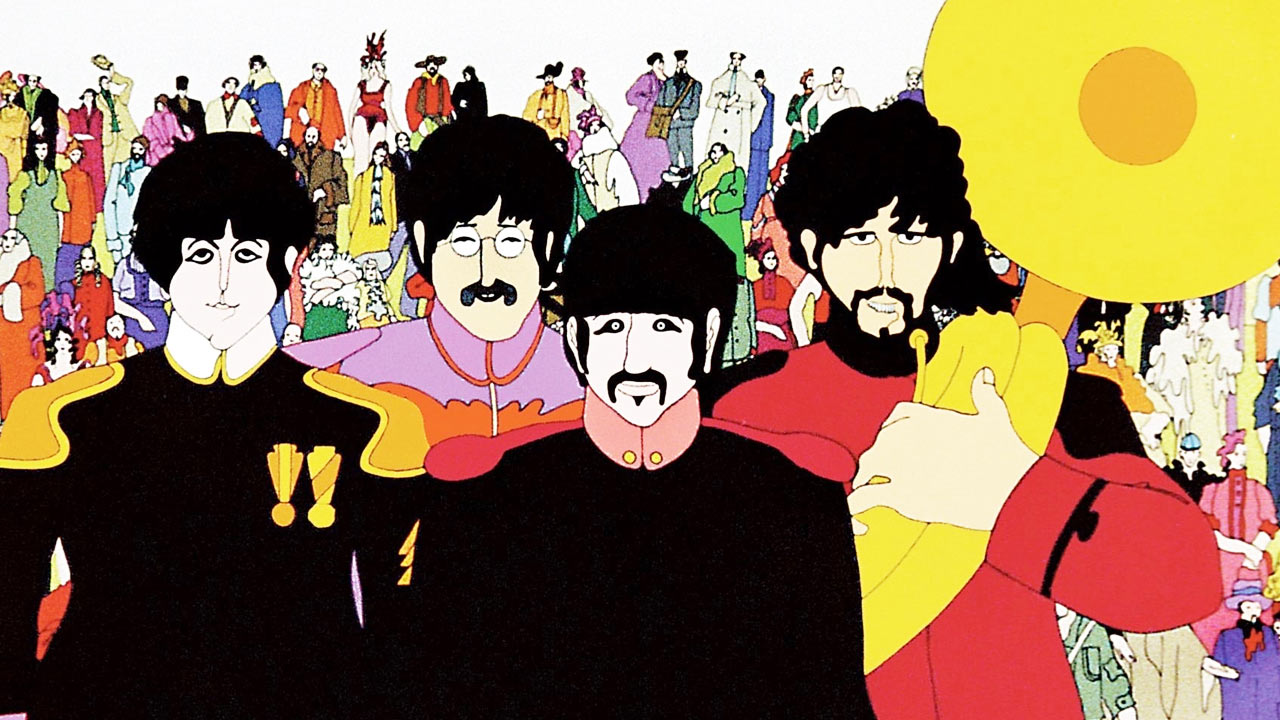

As we prepare for this epic Beatles tour, it’s a fitting time to revisit their most enigmatic film. Emerging in 1968, Yellow Submarine is a unique animated concert film which visualises the psychedelic voyage of the album of the same name released the following year. With the medium of animation predominantly associated with child audiences at the time, the move away from the quasi-documentary style of films like A Hard Day’s Night was radical but in-keeping with The Beatles’ inventive sensibilities.

A Beatles movie…without the Beatles

Perhaps the strangest part of Yellow Submarine is that John, Paul, George, and Ringo aren’t actually played in the film by, well, John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr.

After being dissatisfied with their second film, Richard Lester’s Help!, they attempted to complete their three-film contract with United Artists by being involved as little as possible. To meet the contract specification that they would appear, a short live-action coda sees the four in little more than a cameo. To call it a “Beatles film” perhaps assigns the band too much credit.

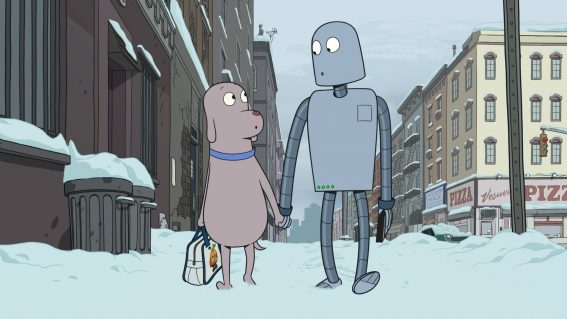

The result is a segmented film driven by songs written for the film, much like Disney’s Fantasia with the animated images corresponding to the lyrics. Taking Yellow Submarine as its driving force, the titular vessel is cast away from Pepperland across the Seas of Time, Science, Monsters, Nothing and Holes as The Beatles journey to drive away the Blue Meanies. In the end music and love triumph, celebrating the hippie values of the 1960s.

Creating acid hallucinations for mainstream audiences

So if not The Beatles themselves, who should be credited for this baffling odyssey?

Director George Dunning oversaw the work of over 200 artists over a period of eleven months assembled from across the world of animation. With the assistance of American animators Robert Balser and Jack Stokes, Dunning worked with designer Heinz Edelmann to recreate striking acid hallucinations palatable for a mainstream audience. The film’s enduring legacy, with a 50th anniversary restoration released in 2018, proves that those sequences continue to capture the imagination of new generations.

Standing in stark contrast to the rest of the film, Charlie Jenkins single-handedly created the ‘Eleanor Rigby’ sequence which moves from The Beatles’ home of Liverpool to London. Unlike the poppy primary colours of the other musical sequences, this scene is largely set in harsh strokes of black-and-white, somewhere between Roy Lichtenstein’s comic-strip works and the collages of Richard Hamilton.

The images are of a crumbling Britannia—Union-Jack-wearing bulldogs and dirty red telephone boxes. It’s the humdrum drabness of life that The Beatles as artists offered audiences an escape from.

From grubby reality to the land of make-believe

The backgrounds of the film were completed by Millicent McMillan and Alison de Vere, the latter appearing as one of the photographed characters in the ‘Eleanor Rigby’ sequence. De Vere went on to create some of the most visually striking animated shorts broadcast by Channel 4, including The Black Dog and Psyche and Eros. Her work is seen across Yellow Submarine, crafting the vivid dynamic backdrops far-removed from the static ones used by most hand-drawn animated films. But the darkness and style of ‘Eleanor Rigby’ appears to have had the strongest influence on de Vere’s later films.

Perhaps the other most successful sequence is that scene’s antithesis, the dancing flapper-like figure of ‘Lucy In the Sky With Diamonds’. Where ‘Eleanor Rigby’ is grounded in grubby reality, this song goes to a land of make-believe replete with “tangerine trees and marmalade skies.”

Dunning himself conceived the psychedelia of ‘Lucy In the Sky With Diamonds’, animated by Bill Sewell through a rotoscoping process which inspired later films including A Scanner Darkly by Richard Linklater. Considering these two scenes together, Yellow Submarine showed that animated films don’t have to conform to a single vision or style.

The remake that never was

In 2009, Robert Zemeckis was in talks with Disney to remake Yellow Submarine as a 3D computer animation in the same style as his films The Polar Express and A Christmas Carol. The project was even announced at D23 and had a cast including Peter Serafanowicz and David Tennant. However, with the flop of Mars Needs Moms, Disney moved away from motion-capture technology in animated films and closed Zemeckis’s studio ImageMovers Digital. Test footage exists, and while the style has failed to hold up, it’s remarkable that Yellow Submarine continues to inspire experimentation in animation.

It might not be long before the world is given a similar film to Yellow Submarine—with the feminist reclamation of 1997’s Spice World, the Spice Girls being set to return to the big screen in an animated superhero adventure. With over fifty years of development in animation, it’ll be interesting to see what an update on the format pioneered by Dunning and his crew of animators will look like. In the meantime, get back toYellow Submarine—and let’s hope someone will make a documentary about the extraordinary production process behind it.