Forget Bob Marley: One Love and watch these great music biopics

Seen That? Watch This is a semi-regular column from critic Luke Buckmaster, taking a new release and matching it to comparable works. This week, dissapointed by Bob Marley: One Love, he revisits four of the best music biopics.

It didn’t take long into Bob Marley: One Love for me to think “oh no, not again.” Not another great musician reduced to a trope-filled milk-and-water biopic. Pioneering artists such as Marley often circumvented or redefined conventions en route to carving out their space in musical greatness—which is partly what makes these heavily codified, same-old productions such tough pills to swallow. It feels terribly deflating to watch a bold artist depicted so meekly.

As I wrote in my review: “Painting legends through formula is risky business, perpetuating the iconography of the subject through boilerplate codes and conventions.” So, what does a truly impressive music biopic look like? What qualities define them? Perhaps the best way to answer these questions is to draw attention to some outstanding examples. Here are four, each film taking very different forms and structures.

What’s Love Got to Do With It? (1993)

What's Love Got to Do with It (1993)

Brian Gibson’s biopic of Tina Turner has a specific thematic focus: as much as it’s about Turner’s life, career and stardom, it’s also about the horrors of a woman trapped in a violently abusive relationship. The director’s approach, informed by the subject’s memoir, seems to have been: get people in the door with the “Queen of Rock ‘n’ Roll”, then serve them hard-hitting socially conscientious drama. This services a historically under-represented topic in cinema while highlighting the strength and courage of its subject. We deeply empathise with Turner, thanks largely to Angela Bassett’s rousingly multi-layered performance.

The first scene, capturing a very young Turner admonished by a choir master for being too performative, leans into the legend, though not in ways that feel hyperbolic or too fanciful. The narrative charts her meteoric rise and relationship with the violently abusive Ike Turner, played with terrible convincingness by Laurence Fishburne. His ghastly presence turns the musical scenes in What’s Love Got to Do With It? into moments of exquisite reprieve. Whenever Bassett takes to the stage the film—not just the character—sings.

Behind the Candelabra (2013)

From the moment Michael Douglas appears on stage as Liberace—dressed in an outrageously sparkling silver suit, playing a gaudily decorated piano, regaling the crowd with banter—this film is magic. Plotwise it’s light, and focus-wise it’s tight, director Steven Soderbergh (adapting Thorson’s memoir of the same name) sticking closely to Liberace relationship with animal trainer Scott Thorson (Matt Damon), who the superstar pursues despite an immense age gap. Their differences in age, maturity and living circumstances create some very, shall we say, mixed feelings, evinced when a pillow-talking Liberace expresses his weird desire “to be everything to you Scott: father, brother, lover, best friend.”

You never doubt Liberace’s ability to charm, because Douglas is so immersively radiant. And you really feel the ups and down of the pair’s relationship, the lust and lustre of young romance eventually bottoming out into bitter separation. It’s Thorson, rather than the star, who gets possessive and unhinged, which changes both the film’s story and surface, Soderbergh’s camerawork growing bolder as Thorson gets wilder. The film’s final act is bittersweet, and the overarching tone celebratory.

Bird (1988)

There’s no such thing as perfect jazz: a greast deal of its beauty comes from discordance and intuition. In his film about legendary saxophonist Charlie “Bird” Parker (Forest Whitaker), director Clint Eastwood suggests that a film’s form and structure might also be semi-improvisational and instinctive, or at least channel this kind of energy. Eastwood doesn’t delay the main event, whooshing us onto a stage with Bird as he makes a beautiful racket, blasting and bebopping and doing his thang. Before long the protagonist is in rehab following a suicide attempt. From the start you can feel the film moving in slightly strange, drifting rhythms, like Eastwood is trying to softly surprise us, like he doesn’t want to deliver the expected beats.

Whitaker’s great performance is the glue holding the drama’s smooth-flowing vignettes together (with rock-solid support from Diane Venora as Bird’s romantic partner Chan Parker). You’re not sure if the drug-afflicted Parker is too far gone, down too deep to come back up. Whitaker gives him an unsettling, vacant countenance, the look of a man slowly being washed away. Eastwood doesn’t make the mistake of trying to explain jazz, or the artist, or the creative process, though the film radiates a love of all these things.

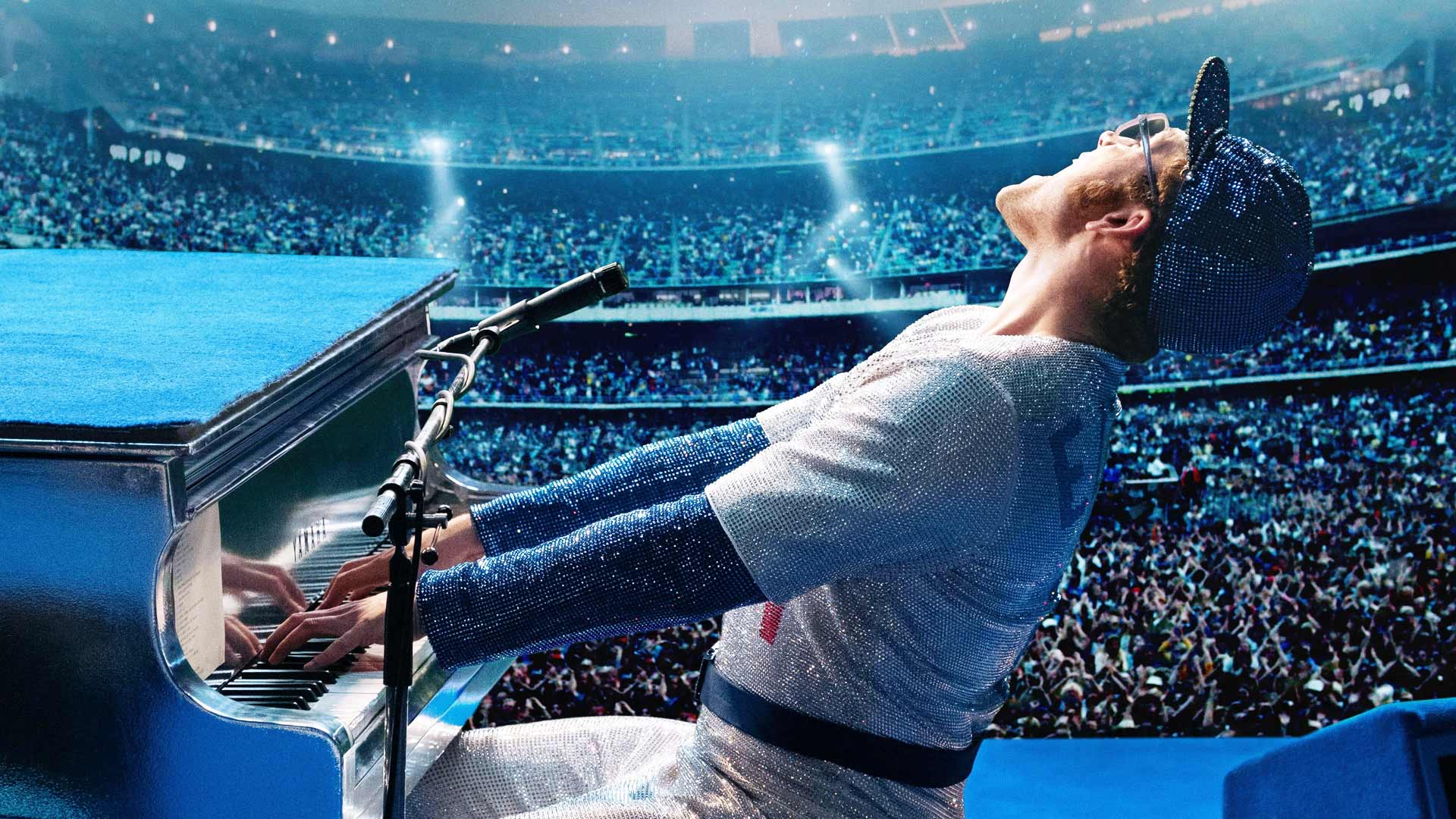

Rocketman (2019)

Recreating past events is impossible; the real challenge in a biopic is to use fiction to be truthful. Director Dexter Fletcher’s film about Elton John is a fabulous example of this, bridging the gap between reality and make believe, creating a spirit that’s fundamentally Elton. This is clear from the very first scene, in which the titular Rocketman (Taron Egerton) attends an AAA meeting in a bright orange birdman costume, then starts singing—the film is a musical, by the way—after his childhood self appears in the room.

As I wrote in my review, this scene, which transitions into a chapter illustrating his childhood in northwest London, is “the first but far from the only example of a film that treats narrative segues as unique entertainment propositions, merging time and space with fussy panache, rendering the past as a kind of phantasmagoric pageant or glitter glue-bound history lesson.” Like all musicals, Rocketman has a heightened theatricality, as well as, less commonly, a thick campy surrealism, enabling Fletcher to zhuzh up many familiar elements—from breakthrough performances to confrontations with tsk-tsking parents.