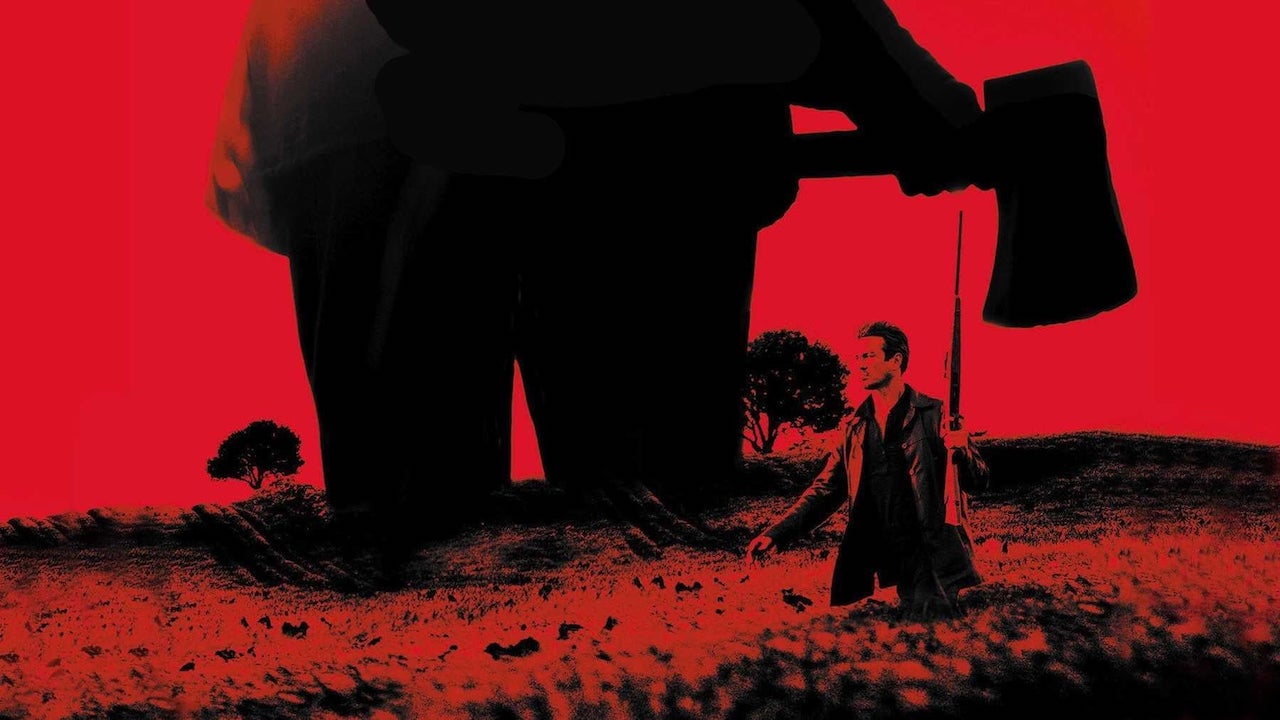

British revenge masterpiece Dead Man’s Shoes is still burned into our brains

Shot over three weeks on a miniscule budget, Shane Meadows’ devastating tale of a brother’s (Paddy Considine) violent revenge is getting the re-release it deserves. Matt Glasby examines the lasting impact of Dead Man’s Shoes.

When I first saw Dead Man’s Shoes as a young man, at a half-empty cinema in Exeter, Devon, I came out changed. I’d never seen a revenge story play out in the melancholy English backwaters, a million miles from Hollywood; or screen violence that seemed so much like the violence in my own heart. In the foyer, a student journalist asked for my thoughts, but I couldn’t muster them. I was floored.

Talking to friends and colleagues over the years, I’ve found it had a similarly shattering effect on them, especially the men. We’d all seen Death Wish, Taxi Driver, First Blood and the rest, but this was so much more potent. As director Shane Meadows put it to journalist Jamie Graham: “There’s something in the veins of Dead Man’s Shoes.”

“God will forgive them,” begins a sparse voiceover. “He’ll forgive them and allow them into heaven. I can’t live with that.” It belongs to ex-soldier Richard (Paddy Considine), who returns to an unnamed Midlands town to haunt its bars and backstreets with his younger brother Anthony (Toby Kebbel), who has learning difficulties, in tow.

Over the course of five days, Richard enacts a campaign of violent intimidation against the people who tormented Anthony—local dealers Herbie (Stuart Wolfenden), Soz (Neil Bell) and Tuff (Paul Sadot), their boss Sonny (Gary Stretch) and his henchmen Gypsy John (George Newton) and Big Al (Seamus O’Neill)—moving from breaking and entering to murder. Gradually, in black-and-white flashbacks, we realise the extent of what they’ve done, and why they deserve everything they get.

As in Meadows’ best work (This Is England, The Virtues) every frame feels personal. Considine and Meadows, who co-wrote the script together, have known each other since college. The film begins with grainy home movies of baby steps and half-remembered Christmases; ends with a dedication to Considine’s late father, who urged him to work with Meadows again after 1999’s A Room for Romeo Brass; and the two children featured are Considine’s nephews. If it feels real—too real at times—some of it is. The film was shot on location in under three weeks, with a stripped-back crew, very little lighting and lots of improvised dialogue. But the restrictions only add to the raw textures.

Because Warp Films was the producer, the much-lauded soundtrack, which moves from the lonely Americana of Bill Callaghan and Calexico to aural assaults from dance acts such as Aphex Twin and Laurent Garnier, was cobbled together cheaply from artists on the Warp label. With his psychopath eyes and deliberate, drilled-in movements, Considine gives one of the all-time great screen performances as Richard.

“I’m not threatening you mate,” he tells Sonny in one of the film’s most iconic moments. “It’s beyond fucking words. I watched over you when you were asleep and I looked at your fucking neck and I was that far away from slicing it.” Half-smiling, he holds out his hand, palm pointing upwards. “You’re fucking there mate,” he says, stabbing it with his finger. (For some light relief, see Paddy re-enacting the scene below with Charles Petrescu, the ungainly robot from Brian and Charles.)

In his screen debut, Toby Kebbell is heart-breaking as Anthony. Apparently the original actor dropped out, concerned about playing someone with learning difficulties, but Kebbell gives the character depth and dignity. He’s always thinking—trying to compute events as they spiral out of control around him—his head bowed low, happy to be in Richard’s shadow. You want to protect him, even as you know you can’t. “I think that’s why it’s stayed with people,” Meadows told writer Kevin Ibbotson-Wight. “There’s a piece of you that wants revenge yourself as you’re watching.”

Sonny should be a pathetic figure, driving around the sad estates in a Citroen CV, hip-hop blaring from the speakers, and his gang crammed in the back. But Stretch, an ex-boxer, has such a powerfully malevolent presence, like a black hole in human form, he’s terrifying instead—or maybe as well.

The supporting cast, particularly Wolfenden, Bell, and Sadot, bring such warmth and relatability to their roles that you almost feel sorry for them—until you see the terrible things they’re capable of. But then, as the filmmakers know all too well, most terrible things are done by ordinary people. Describing the Midlands town he grew up in, Considine told journalist Thomas Leatham of “atrocities that had gone unnoticed and unrecognised; horrible things that had happened and been done in the name of leisure almost.”

Meadows, meanwhile, has spoken candidly about being sexually abused by older kids as a child, and of a friend who committed suicide after being bullied. “I grew up in a place where if you had a weakness of any kind, you were preyed upon,” he told Ibbotson-Wight. “And if you hadn’t got someone there to protect you or to look after you, you were dropped into a flat or a house with these fucking serpents.”

Unlike its Hollywood equivalents, when violence erupts in Dead Man’s Shoes, it’s brief, ugly and shocking—a twisted knife in the stomach here; a “super-duper fucking dose” of drugs there—and we’re never allowed to forget the fallout. It’s not just that violence begets violence—we’ve all seen that before—it’s that it leaves a stain on the soul of everyone it touches. That’s why Meadows and Considine are still reliving their childhood traumas; why Richard’s revenge destroys him, destroys everything; and why the film burns itself into the brains of its viewers, whether victims or aggressors, or both. There’s just something in its veins.