Retrospective: before The Great, there was Marie Antoinette – ignore 2006’s reviews, it’s pretty great too

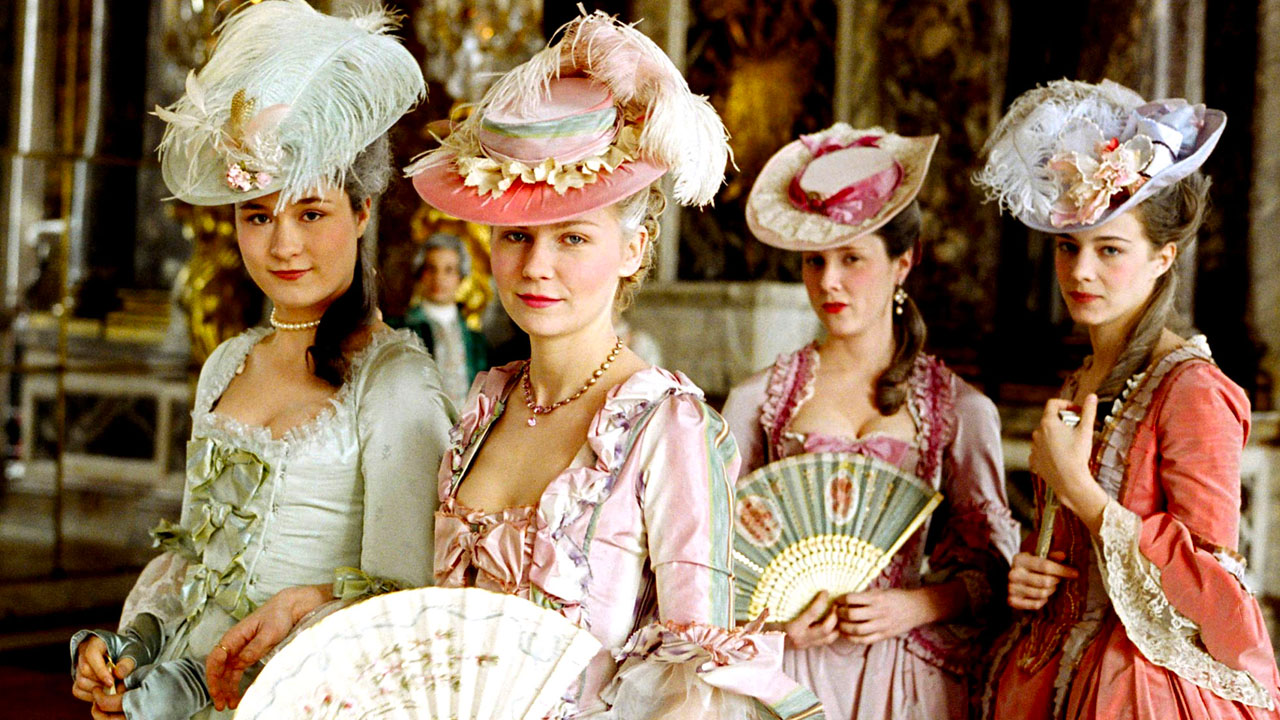

Booed at Cannes and dismissed by critics, Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette nevertheless holds up remarkably well. Amelia Berry explores just why people got it so wrong back in 2006.

In 2003, Sofia Coppola won Best Original Screenplay at the Academy Awards for Lost in Translation. It also netted two other Oscar noms, won three Golden Globes, three BAFTAs, and launched a trend for cheap pink bob wigs that would continue unchecked for a decade.

Three years later, her follow-up feature Marie Antoinette was booed at Cannes.

Now, Roger Ebert might try and tell you that only a few people booed, and that booing is just how the French tell you you’ve made some slight historical inaccuracies, but looking back at reviews of the film from 2006 is to witness a loud and sonorous boo echoing obnoxiously through time. Sure, there were some positive reviews (including Ebert’s own), but they were starting off on the back foot, having to explain that, despite what you may have heard, Marie Antoinette is good actually. And you know what? They’re totally correct. In 2021, it’s hard to deny that Marie Antoinette holds up remarkably well. So then, why did people get it so wrong back in 2006?

The short answer is (no points for this one) sexism. But just saying that doesn’t tell you much. The slightly longer answer is that 2006 was an all time low for the understanding of camp and irony, particularly in regard to media directed at women. Which is better, but involves some unpacking.

So, picture this. The year is 2006. You’re in the car, driving to see an afternoon showing of The Da Vinci Code. It’s not great, but you want to be in on the conversation. You turn on the radio. Everytime We Touch by Cascada is playing. Awful! You change the station. Now it’s Long Way 2 Go by Cassie. God, who listens to this awful rubbish. Poptimism hasn’t been invented yet, you’re not an emo, and the early 2000s rock revival has pretty much burnt itself out already, so you put on the first Razorlight album and just grin and bear it.

For most people, being politically conscious in 2006 means hating Bush and loving poor-hating eugenics comedy Idiocracy. Being ironic means wearing ugly t-shirts and being racist “as a joke”. Camp means something about those gay Franz Ferdinand songs, maybe? Needs more research. The television show Nathan Barley came out in 2005 satirising trendy VICE critic culture, but nobody really understood what it’s trying to say until 2010 when its message was synthesized into the song Being a Dickhead’s Cool. This is 2006.

Hand in hand with the critical disdain for pop music, long considered the unserious domain of teen girls, was an open ridicule for “vapid rich girl” celebrities like Jessica Simpson and Paris Hilton. In film, grim-dark was in. Alongside Children of Men, we get Casino Royale, The Departed and The Prestige. We’re just two years away from the beginnings of comic book movie ascendency with The Dark Knight and Iron Man in 2008.

All of this to say, many critics at the time did not know what to make of Marie Antoinette at all. It’s about women, for women, but with some kind high-brown arthouse aesthetic? This comparisons made highlight this confusion:

“Sure, she’s vapid, spoiled, and self-indulgent, but she’s more recognizably human than any of the girls on Laguna Beach or My Super Sweet 16.”

“The whip-smart makers of The Queen show us how the other half lives by imagining how they think; Coppola tries to show us by merely demonstrating how they dressed.”

“I don’t know why I kept thinking about Paris Hilton while watching Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette. Perhaps because the film looks good “all fluffy and pink” but decidedly empty when it comes to plot and emotional implementation.”

“As for Dunst, there’s nothing she does here that couldn’t have been done by Jessica Simpson.”

Much of this criticism boils down to Marie Antoinette reminding writers of young women they dislike. The film (they say) is, like these women, dull and empty. Focused on surface. Expensive but boring. Not to mention the similarly focused attacks on Coppola herself. The other major criticism is that it lacks the seriousness and scholarship of better historical films, like say (forgotten Helen Mirren vehicle) The Queen. Comparison is also made to Barry Lyndon, and while the two share a costume designer and are both exquisitely shot, the tone couldn’t be more different.

At its core, Marie Antoinette is a film that works with two main ideas. The first is a celebration of the history of the feminine in cinema and so, to a large extent, the history of camp in cinema. The second is the dark irony of playing out a story of a young woman’s life against the known quantity of her brutal death. The problem is, that both of these ideas demand that we take women and femininity seriously, and that we recognise that vanity, foolishness, and imprudence do not strip away a person’s humanity, even if that person is a woman. This is something which becomes more difficult, the longer you’ve spent being a dick about the contestants on Flavor of Love.

At the risk of becoming the 2019 Met Gala, camp in cinema is aligned with exaggerated femininity in cinema. To, again, oversimplify massively, this falls into two main categories. First is melodramatic exploration of female pain and loneliness (think All About Eve). Second is over-the-top pop-culture cash-ins of unabashed girliness (think The Simple Life, or any of those Mary-Kate and Ashley movies).

Coppola draws on both these traditions, having Kirsten Dunst enact Antoinette’s arrival at court with a Princess Diaries-esque, fish-out-of-water goofiness, playing it for tragedy in the face of the future Queen’s grim fate. As Antoinette grows older, she revels in eccentricities she once rolled her eyes at, eking out what happiness is possible from (for example) performing as a milkmaid in a one woman show. As her growing insularity alienates her from the court, we see her pain in feeling unable to live how she ought to.

Also she has a fantasy about Jamie Dornan riding a horse sexily. It’s extremely camp! Massive dresses and crushed dreams! RuPaul’s Drag Race wouldn’t air for another three years, and unless you were staying up ‘til 2am with your headphones plugged into the TV to watch The L Word, queer visibility at this time was largely assimilationist calls for gay marriage. This combined with a pervasive misogyny, meant that this exploration and celebration of camp read to many contemporary viewers as foolish, shallow, and petty.

That Marie Antoinette is saying something political, social, philosophical, seems straightforward. It opens with Natural’s Not In It by UK post-punk band Gang Four, a song that is pretty nakedly about the commodification of sex. Quite an on-the-nose way to start a film about a woman whose bosom allegedly inspired a range of popular glassware.

Critical consensus in 2006 held that the film was pretty but lacking in substance, plot, or suspense. Some even criticised Coppola for focusing the film within the palace. Where are the scenes of rising peasant tension, political conspiracy etc.? The beauty and tension of Marie Antoinette, however, is precisely in the omission of these. We know enough about Marie Antoinette to know that she dies. That her family dies. That the people of France are being treated terribly and resent the decadent aristocracy. This hangs over the action of the film, colouring every scene, every conflict.

When Antoinette tries to adjust to court life, when she worries over conceiving, when she overspends and indulges, we know that soon she will die. Fatalism is essential to tragedy, and Marie Antoinette is the tragedy of a woman who had little choice, and no power. A girl forced to become a symbol for the monstrosity of Monarchy. Of course, if you cannot extend your empathy to the girl at the centre of the story, if you cannot trust the filmmaker to tell a layered story, all of this melts away.

Watching in 2021, Marie Antoinette is not just a good film, but maybe even a better film than Lost in Translation. Putting aside Translation‘s poorly aged caricature of Japan, a more interesting comparison is in the character of Kelly (played by Anna Faris). The closest thing Lost in Translation has to an antagonist, Kelly is ridiculed by Scarlett Johansson’s Charlotte for being just the kind of vapid, rich girl that critics saw rehabilitated in Marie Antoinette. Eating disorders are so gauche, how tacky, doesn’t she even know that Evelyn Waugh is a man? Her crime seems to be little more than being sweet, oblivious, and pretty. Watching the film back today, it’s hard to summon up much spite for that.