Beau is Afraid is about mummy issues, sure—but it’s also about creation

Frustrating and fascinating audiences in equal measure, Ari Aster’s latest film funnels his usual horrific themes through a more self-reflexive lens. Eliza Janssen finds the meta subtext of Beau Is Afraid, but be afraid: there are spoilers ahead.

Beau Is Afraid

After two well-received horror films about warped family horror, director Ari Aster is getting somewhat mixed reviews for the concluding chapter in this triptych: the more undefinable, comedy-tinged Beau Is Afraid. Twisted motherhood is right there in the title of Hereditary, and Midsommar has Florence Pugh’s traumatised protagonist assimilate into a new family of bright happy cultists after her own kin are distressingly killed off by her sister in the cold open. So here Aster is again, casting Joaquin Phoenix as a middle-aged neurotic facing torturous trials to reconcile with his controlling mother. Men will literally make a trio of films about horrific maternal destruction instead of simply going to therapy, etc etc.

Thing is, the titular Beau is giving therapy a go when we first meet him, and it’s not having much of a positive effect. No amount of introspection can really fend off the hallucinatory scenes of violence and chaos happening outside his dingy apartment—plateaus of twerking topless strangers, tattooed attackers and dead bodies that the film never pulls away from to suggest they’re merely Beau’s paranoia. Beau is Afraid can be closely compared with the Coen brother’s tragicomedy A Serious Man, wherein another beleaguered Jewish loser sees his domestic life spiral into near-supernatural disaster. Hell, both films feature Richard Kind, and the same deadpan dark comedy that makes a viewer chuckle and foolishly ask, “jeez, how much worse can things get?”

When one such string of calamities is capped off by Beau learning that his mother has been crushed to death by a chandelier, his sole motivation is to attend her funeral. A wealthy and powerful CEO in life, she’s commanded her only son to see her body before it’s buried ASAP after death, in keeping with the Jewish mourning tradition of shiva. But this seemingly simple objective is hindered by Beau’s physical and, as we learn, emotional state: trapped in Nathan Lane and Amy Ryan’s dysfunctional suburban set-up and then chased into a woodlands theatre troupe, Beau (and we) can’t quite figure out why the universe won’t let him grieve his lost mum.

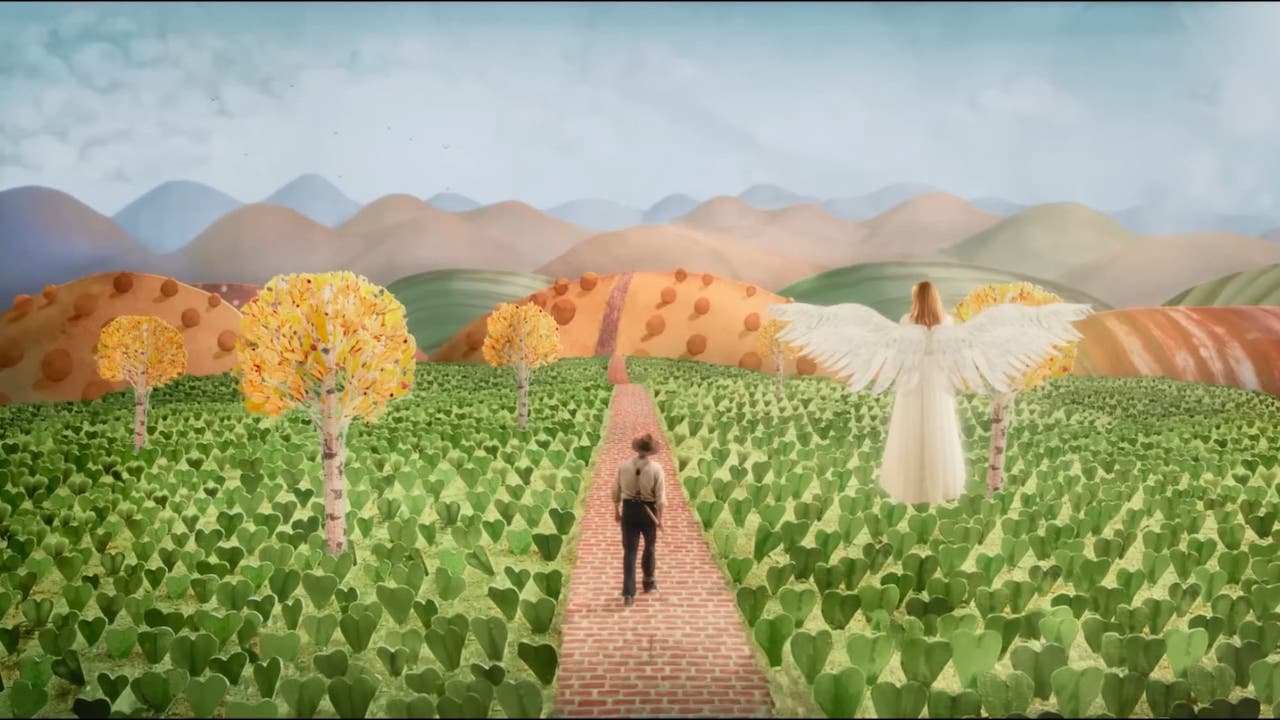

A partially-animated fantasy sequence in the second act of the film has drawn praise for its visuals from critics. But it’s also the point at which Beau Is Afraid loses its momentum, petering out from one unpredictable shock into the next leading to a bummer of an ending. Having finished the film and sat with it for a few disturbing moments, Beau’s sumptuous dream of building a parochial family life, losing it at sea, and then redemptively reuniting with his sons as an old man feels like the only moment in the film where the character has any semblance of control. This extended imagination, Aster seems to be telling us, is the only part of this implausible nightmare epic that we can trust, and tragically it’s a complete fiction—crafted in stop-motion, dinky stage-play sets, and Midsommar-bright colours.

After blessing us with some of mainstream horror’s most inventively haunting scenes in recent memory—Toni Collette scrambling out of a darkened room’s corners, elders tumbling from an idyllic blue sky onto a ceremonial death-rock—much of Beau Is Afraid feels like a self-conscious artistic flex. Perhaps Aster hasn’t strayed too far from pointing the finger at oppressive parental forces victimising their weak offspring here, but he does seemingly cast himself—or filmmakers in general—as an antagonistic force within the film. We finally meet the in-world auteur of all this seemingly random havoc, Beau’s mother Mona (Patti Lupone), and the film’s Freudian terrors come into focus.

In a twist that’s not so much revealed as slowly spewed into our laps over the course of three hours, it turns out that every tormenter and ally Beau has encountered in his life has been on Mona’s payroll—and yet she’s still murderously angry at him for failing to make it to her shiva. For inevitably growing into the manchild he is, who feebly bitches about his mother in therapy. Her cruellest deception was telling a juvenile Beau that for him, sex would be fatal, a lie that’s ironically subverted when he finally beds his childhood crush Elaine (Parker Posey, brief but brilliant) and it’s she who inexplicably drops dead.

The emasculating delusion has had such a grip on Beau, he’s barely had any mental space left to seriously ponder his missing dad…until Mona reveals dad’s true fate hidden in her home’s attic. Inside is Beau’s chained-up double (either his forgotten, disobedient brother, or a physical representation of his spiritual malnourishment) and a giant bellowing penis monster. I am not being hyperbolic: a huge, physical-effects dick is apparently Beau’s father.

It’s kind of a visual gag, kind of a questionable peep into Mona’s man-hating psychosis: the men in her life have done nothing but let her down, being an emotionally castrated son and an unfeeling phallic beast. She strands Beau in a kangaroo court where his crimes of failing to honour thy mother lead to a death sentence before an arena of grey employees. He is drowned, Mona weeps, and the credits roll. And roll. Mona’s workers silently trail out of the dystopic, unreal setting while we watch to make sure Beau doesn’t resurface (he doesn’t).

I wonder what the experience of streaming Beau Is Afraid will be like, as this ending is perfectly calibrated to mirror how a cinema audience responds to the narrative. Having accompanied Beau on a senseless obstacle course of pain and humiliation, the lights go up and we walk out, bewildered, once Aster’s name appears onscreen. To me this conclusion confirms that Aster isn’t content to just retread his past themes of parental abandonment and inherited trauma: as a horror director, he’s showing us the awful power of even crafting art like this. For Mona, it’s an obsessive staging of her lifetime’s maternal rage, casting actors to ruin her son’s future, sexuality, manhood, and still feeling furious when he turns up ruined before her. For Beau, he’s a directionless spectator to the madness, except for that brief sequence of escapism he can briefly comfort himself with before the end of his story.

The repressed and repulsive depiction of sex in the film speaks to its broader ideas about creation. When a man and a woman love each other very much, Beau Is Afraid pessimistically explains to us, they get together and produce something that destroys both of them, dooming their product in turn. When an artist and their collaborators strive to create something meaningful, it reveals the worst nightmares of their audience and themselves, perhaps only being misinterpreted or read as an “expensive public therapy session with an overcomplicated script“. Like Oedipus’ self-fulfilling prophecy, we scrabble for creative control over what we make, but we’re doomed to see it turn against us.

Compared to the horror-fan-pleasing structure of Hereditary and Midsommar, Beau Is Afraid has left critics and audiences scratching their heads. But its style-over-substance sensibility and duration, both of which have been denounced as indulgent, are in my mind justified by the story’s deeper themes of creativity and narrative in general. It’s practically a three-hour-long panic attack with some uncomfortable laughs thrown in—whether you like it or not, I’m sure Aster is a pretty proud parent.