A deep dive into the cinematic beauty of The Last of Us Part 2

The PS4 video game The Last of Us Part 2 is one of the best-selling works for art released this year. Critic Luke Buckmaster explores the game’s striking use of cinematic artistry.

When I reacquainted myself with the original The Last of Us, returning to this magnificent video game in the lead-up to the arrival of its sequel, a strange synergy existed between the narrative world and the real one. In Naughty Dog’s 2003 action-adventure, a pandemic for which there is no vaccine has devastated the United States and upended civilised society.

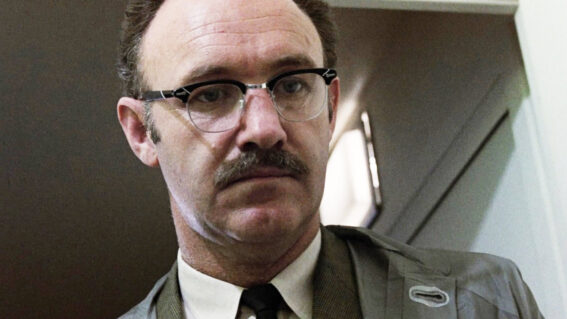

I played the game again roughly two months into the outbreak of COVID-19—the real world’s very own pandemic—and finished the intensely gripping The Last of Us Part 2 this week. My hands were almost trembling by the end, and my eyes as wide as Malcolm McDowell’s in A Clockwork Orange. It registers a higher emotional impact than its predecessor, with a bolder narrative structure and more morally challenging ideas. I think it’s a superior work.

In the time between playing part one and part two, society around me had slid further down the COVID-19 wormhole. At the time of publishing there have been close to half a million coronavirus casualties worldwide and more than nine million cases, plus all kinds of cultural and economic disruption.

The Last of Us Part 2 is also based further down the track than the original. Five years have elapsed since the principal characters, Ellie (voice of Ashley Johnson) and her father-like figure Joel (voice of Troy Baker), first trekked across a ravaged America, combating all sorts of human and once-were-human foes. This is a dystopia but not a wasteland, because wastelands are synonymous with ugly and devastated terrain. It’s more a wasted civilization, societal breakdown contrasted with the gorgeous return of the natural world, re-emerging to take over buildings and public spaces.

The virus has eliminated most of humankind—like in films such as 12 Monkeys and Le Jetee—but the natural world is going just fine. The game’s writers (Neil Druckmann and Halley Grossand) and directors (Anthony Newman and Kurt Margenau) reject the hubristic human view that the world is fundamentally ours: designed for us and ours to ravage and pillage as we please, its fate and ours intravenously connected.

The pandemic depicted in both parts of The Last of Us is of course more dramatic than ours—and also more cinematic, though I’ll return to that word in a moment. A terrible virus called the Cordyceps fungus transforms human beings into creatures known simply as the Infected, which are in effect zombies: horrible, snarling, drooling, flesh-chewing beasts with, shall we shall, a severe absence of moral compass—like Trump voters or Australian Young Liberals.

In the opening moments of The Last of Us Part 2, I noticed, after excitedly loading it for the first time, a person’s name appear below the credit ‘Lead Cinematic Lighting Artist’.

It’s not surprising that this job comprised somebody’s entire contribution to the production, given the lighting is so striking. The way it radiates from the sky during sunset and sundown, warm and omnipotent, or the way it billows through windows, or emanates from wooden torches illuminating forests at night, or beams out of high-powered spotlights.

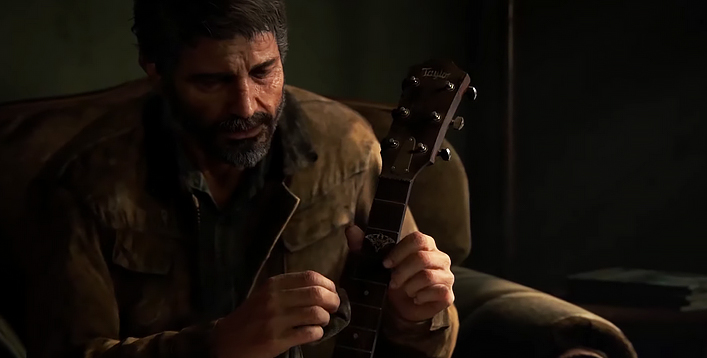

The first shot in The Last of Us Part 2 is a close-up of an acoustic guitar, which becomes a visual motif throughout the experience, the guitar also being an instrument you play at a few points in the running time. This opening image begins close:

Then slowly pulls back to reveal a forlorn-looking Joel (a dead ringer for Josh Brolin) cleaning it:

From the opening moments the game looks richly cinematic. But what does that word even mean? I’ve been critiquing films for more than two decades and still struggle to explain it. “Cinematic” no longer has anything to do with screen size, that’s for sure. Nintendo Switch experiences can look cinematic; images on your smartphone can look cinematic. I recently raised this question on Twitter, which generated an interesting discussion.

Nor does cinematic have anything to do with largesse, because even food documentaries can look cinematic—like director Warwick Thornton’s sublime recent series The Beach. Thornton makes a cinematic meal out of oil, spice, meats, noodles and other ingredients, as well as things that might look simple or undramatic in other hands—such as a shot of leather boots on the sand.

From Warwick Thornton’s NITV series The Beach

A few weeks ago I asked Thornton himself what he thinks cinematic means. The director and cinematographer responded jokingly, but not without truth: “It means even if it’s boring as batshit, fuck it looks good…There is no reason why, in any place, or in any shape or form, you can’t be cinematic.”

Like the guitar in The Last of Us Part 2. Or the image of a motorboat—grey-tinged and drained of colour—bobbing about in the menu screen, the relevance of which only becomes apparent towards the end of the game.

Film theorist David Bordwell’s definition of cinematic connects the word to staging, proposing that cinematic staging “delivers the dramatic field to our attention, sculpting it for informative, expressive, and sometimes pictorial effect.”

Auteurs over the years have experimented with various shortcuts to get there, into the land of richly cinematic images. Stanley Kubrick for instance through his grand symmetrical compositions, or Sergio Leone and Akira Kurosawa in their use of wind and motion, or Australian television creator Vicki Madden in her deployment of mist, which, in shows such as The Gloaming, rises over hills like a kind of mystical vapor, making the frame seem like an imbibable element.

From The Gloaming

In addition to evoking cinematic visual qualities, my favourite moments in The Last of Us Part 2 use narrative techniques wedded to the evolution of cinema. Namely its flashback sequences, which for me mark the game at its most emotionally involving.

That term, “flashback”, is linked to a technique invented for the cinema in its early years that rapidly propels (“flash”) the viewer out of the present moment into a narrative past (“back”). Narratives that switched timelines were far from new (appearing in mediums such as literature and theatre) but cinema resulted in the term being coined and brought a new-found immediacy to the process. As Maureen Turim explains in her book Flashbacks in Film: Memory and History, the emergence of the cinematic flashback not just changed cinema, but had an enlightening effect, resulting in critics and audiences being “more likely to recognize flashbacks as crucial elements of narrative structure in other narrative forms.”

A couple of the key flashback sequences in The Last of Us Part 2 create a powerful sense of location; after going there virtually the larger environments in particular almost feel like places we’ve visited in real life. I am going to go into one of these flashbacks now, which I would strenuously argue is not a spoiler. It occurs around six hours in but gives away nothing about the overarching narrative: in fact it is disconnected from it; its purpose to provide character development and emotional context. But if that bothers you, stop reading.

The scene in question is a visit to the Wyoming Museum of Science and History, which Joel takes Ellie (who you are playing as) to on her birthday, as a special surprise. Discovering the life size T-Rex model outside is a lovely moment of wonder: a more understated version of Sam Neil and co. encountering their first dinosaur, a Brachiosaurus, in Jurassic Park, the stillness of a giant model replacing the energy of an active creature, and thus redolent more of death than life—which suits this game to a tee.

The Last of Us Part 2 is constantly considering things that are lost and things that once were. Things that have become, with time, withered simulations of their past, broken down and bedraggled, still with enough visual clarity to reflect the life they once had—from couches overcome by grass and moss being reclaimed by Mother Nature, to long-abandoned shops and public spaces.

To arrive at the museum you follow a river through a beautiful forest, at times diving into the water to overcome obstacles. This journeying builds anticipation and introduces the space in a special way. There are many examples in film and literature of passageways connecting the ordinary world to the magical, famous ones including Alice’s tumble down the rabbit hole and Dorothy’s tornado ride to Munchkinland. Those transitional periods are more dramatic than Ellie’s, but serve the same Huxleyan purpose, ultimately making the point that the person who comes back through the symbolic door in the wall will not be exactly the same as the person who went out.

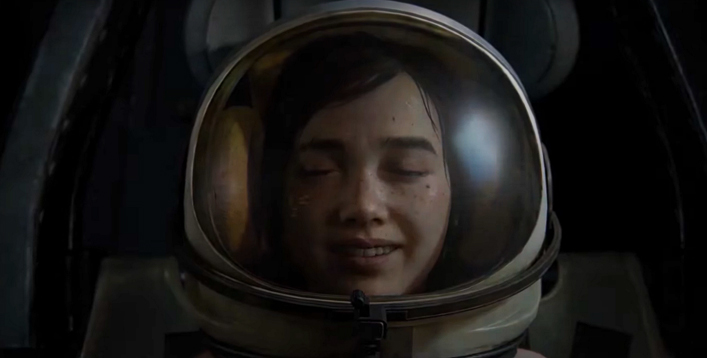

Outside the museum Ellie is ecstatic: “It’s a mother-fucking dinosaur!”, she exclaims. Inside we inspect several displays, including the skeleton of a Brachiosaurus (“imagine the poops!”), before making our way upstairs, to the real surprise—a ‘Walk the Stars’ exhibition, which delights the astronomy-loving Ellie. After checking out various models of spaceships the pair climb into a life-sized space shuttle, marking the transition to a cut scene (and my favourite moment in the game).

Lying down in the designated spots for astronauts, Joel hands Ellie a cassette tape, which she inserts into her Walkman. It is a recording of a spaceship countdown (“30 seconds and counting…20 seconds and counting….”). She closes her eyes, a look of delight splashed across her face, as the camera point-of-view rests above her face, looking down on her.

When the voice on the cassette says “ignition sequence starts”, something special happens. We hear the sound of engines ignite—not in the cassette’s world; in the game world—and observe the side of the frame light up with colour from the imaginary vessel’s flames, bathing the rest of the image in an orange-y glow.

This exquisite long take doesn’t just look cinematic. It also evokes techniques wedded to the cinema, involving a marriage of form and content with exploration of the subconscious. This harks back to foundational elements of film such as the movement of German Expressionism, when productions including the iconic The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari shirked realism in favour of an intensely psychological aesthetic, representing the inner feelings of the characters and the artist.

This movement influenced directors such as Alfred Hitchcock, who toned back excessively symbolic set design and dreamscape-looking mise en scene for more specific pockets of mental impact. The shots of train tracks symbolising criss-crossing in Strangers on a Train, for instance, and the voices Janet Leigh hears in her head in the car en route to the Bates motel in Psycho, full of paranoid speculation about how people will response when they realize she ran off with a bag of stolen money.

In moments like the one above, with Ellie experiencing lift-off in her mind and the audience being taken with her, grounded in the root reality of the game but also whisked along to another world by the aesthetics of the experience, a full arsenal of filmmaking techniques are deployed. Cinemas have been exhibiting live action footage for over a century now, but this is still comparatively new to video games. I remember how revolutionary Wing Commander III felt when it arrived in 1994, featuring long cut scenes starring Mark Hamill. It was marketed with the tagline: “Don’t watch the game, play the movie!”

Now, I suppose, with productions like The Last of Us Part 2, we all watch the game and play the movie, and we all watch the movie and play the game. Boundaries will continue to blur between art forms as technology advances and stylistic practices develop. Far off into the distance, if cinema itself becomes a relic of the past—a kind of museum, not entirely dissimilar the one in virtual Wyoming—the word “cinematic” will probably remain. As will the question of what it really means.