A cinematic analysis of Red Dead Redemption 2, the blockbuster game deeply connected to film history

Does the highly anticipated Red Dead Redemption 2 owe more to the history of the cinema than the history of video games? Critic Luke Buckmaster explores what the smash-hit production means for the western, a genre baked into the very foundation of moving images.

When I started playing Red Dead Redemption 2, the long-anticipated blockbuster production that, when it was released late last month, racked up the largest opening weekend of any entertainment product in history, I found myself wondering: if it were a movie what kind of film would it be? A long, lavish, slow-paced and visually ravishing western, I figured, so large and expensive it would be capable – like director Michael Cimino’s 1980 epic Heaven’s Gate – of bankrupting a studio.

The more I played it the more I thought: this kind of already is a movie. Maybe it was the long and frequent cutscenes that made me think this, or the stylised ultra slo-mo shots that appear at unpredictable points to jazz up moments of action, or the ‘cinematic’ mode presenting various camera angles and on-the-fly editing. Or maybe it was witnessing many moments we’ve come to expect from western movies – such as bank robberies, saloon fights and bullet-riddled enemies falling theatrically from high places.

There are many, many cutscenes in Red Dead Redemption 2. One has the option of watching literally hours of the protagonist Arthur engaging with various people and situations. The majority of the game involves riding horses across a vast and gorgeously rendered Wild West, as if the universe of every John Ford western has been rolled together. Like films that prioritise atmosphere over narrative, a large part of the game’s appeal is tonal. Despite the violence and confrontation this is a pleasant headspace to return to.

Red Dead Redemption 2 owes much more to the history of cinema than the history of video games. The reason the western is such an enduring genre, beyond the obvious appeal of pretty outdoors surroundings populated by gun-toting people bearing grievances, is because it was baked into the very foundation of the moving image. In a sense the cinema began with the western. The highly influential The Great Train Robbery first screened in 1903, and in 1906 The Story of the Kelly Gang – a ‘meat pie western’ – became the world’s first feature-length narrative film.

One of the first images I saw in Red Dead Redemption 2 (before the game started) was a loading screen comprised of a sepia-toned picture of a steam train. The steam train, again, is baked into the very foundation of moving images. Screened in 1986, the Lumiere brothers’ famous short L’Arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat (aka ‘Train Pulling into a Station’) is one of the earliest motion pictures. There are many examples (The Great Train Robbery is one of them) of steam trains being solidified in film history. They represent two bedrock elements crucial to the movies: motion and technology.

Buster Keaton’s 1927 masterpiece The General embraced the train (and the western) as a vehicle, so to speak, with which to combine social myths and historical recreation. So does Red Dead Redemption 2. The myths it trades in are so deeply rooted in popular and cultural consciousness we cannot possibly know where reality ends and legend begins. The only people who might have known that died a long time ago.

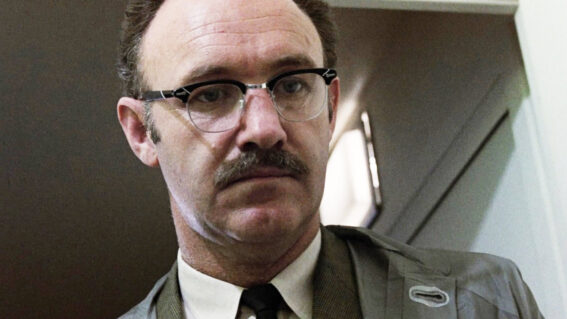

What we do clearly see is an ‘end of an era’ narrative, unfolding circa 1899. We are told that outlaws such as Arthur and his fellow gang members, led by the charismatic Dutch Van Der Linde, are part of a dying breed. A soon to be bygone way of life. There’s an inference that the world has lost something irretrievable, but what did it really lose? These people are thieves, murderers, felons, thugs. You could call them dyed-in-the-wool liberals who believe in the philosophy of small government, or you could call them violent uneducated mongrels.

Perhaps Red Dead Redemption 2 gets romantic about the wrong things (although the writing on the wall suggests the story will not end with the criminals riding off happily into the sunset). It’s not these people we should be sad to see go (there’s another word for their eradication: progress) but the beautiful land we ride across, buzzing with natural life. The advance of man-made climate change suggests a future world where more and more once-natural things will live on like this: as virtual representations. Chimeras; dreams; bio-digital jazz invoking an increasingly distant past.

Much has been said about the game’s supposedly ‘free world’ nature, with hyperbolic discussion about how players are supposedly given carte blanche to do whatever they like and behave however they please. As much as I am fond of this game (at the time of publishing I’ve played for around 30 hours and completed 40% of the story) I am calling BS on this. Red Dead Redemption 2 is one of the most ‘directed’ video games I have ever played. It is less about empowering the player than restricting their choices.

There are many things you can decide to do in addition to the main narrative, from seemingly countless side missions to recreational activities such as fishing, poker and playing dominoes. But in almost every instance the user is told precisely what to do and how to do it. A small list of options is sometimes provided (for example, choosing whether to greet a stranger or antagonise them) in service of a Choose Your Own Adventure style framework, whereby certain choices arrive at predetermined solutions, and more of one thing (i.e. aggression) leads to more of another (i.e. retaliation). Saying the game is intensely directed isn’t necessarily a criticism. It has to be in order for the makers to deliver dramatically interesting and atmospherically rich experiences.

The influential game creator Sid Meier once described video games as “a series of interesting decisions.” That was certainly true of the games he made, such as Civilisation and Civilisation II, because the player’s decisions formed the narrative and the narrative was a manifestation of the player’s decisions. Decide to invade a city and you either take it over or suffer the consequences. Either way the dramatic stakes involve supplies and finances. The narrative did not rely on escorting players to a predetermined point.

Red Dead Redemption 2, on the other hand, tells a specific story and uses an arsenal of cinematic techniques to make it resonate. Make no mistake, these techniques are ‘cinematic’ for a simple reason: they emerged from the cinema. That is not to say the western is the domain of film any more than beautiful lakes or snow-tipped mountains are the domain of oil paintings. As this impressive game reminds us, it is a beautiful thing to experience various kinds of art embracing similar stories in different ways. The western rides on, as glorious and as cinematic as ever.