30 years ago, the BBC horror special Ghostwatch scared the pants off 11 million viewers

On Halloween night in 1992, an authentic-looking BBC found footage film fooled almost a fifth of the nation into fearing a murderous ghost named Pipes. Here’s Matt Glasby, on the enduring trauma of Ghostwatch.

Ghostwatch is not streaming on any subscription service, but can be seen here on The Internet Archive.

It’s not often that you can recall exactly what you were doing 30 years ago, almost to the minute. But on October 31, 1992, at around 22:10, the 12-year-old me was standing in the upstairs bathroom of my childhood home shaking in terror at something I’d just seen on TV. The programme? The BBC’s Ghostwatch, a never-to-be-repeated experiment in extreme audience manipulation. The reason I turned it off? I’d just seen a ghost called Pipes.

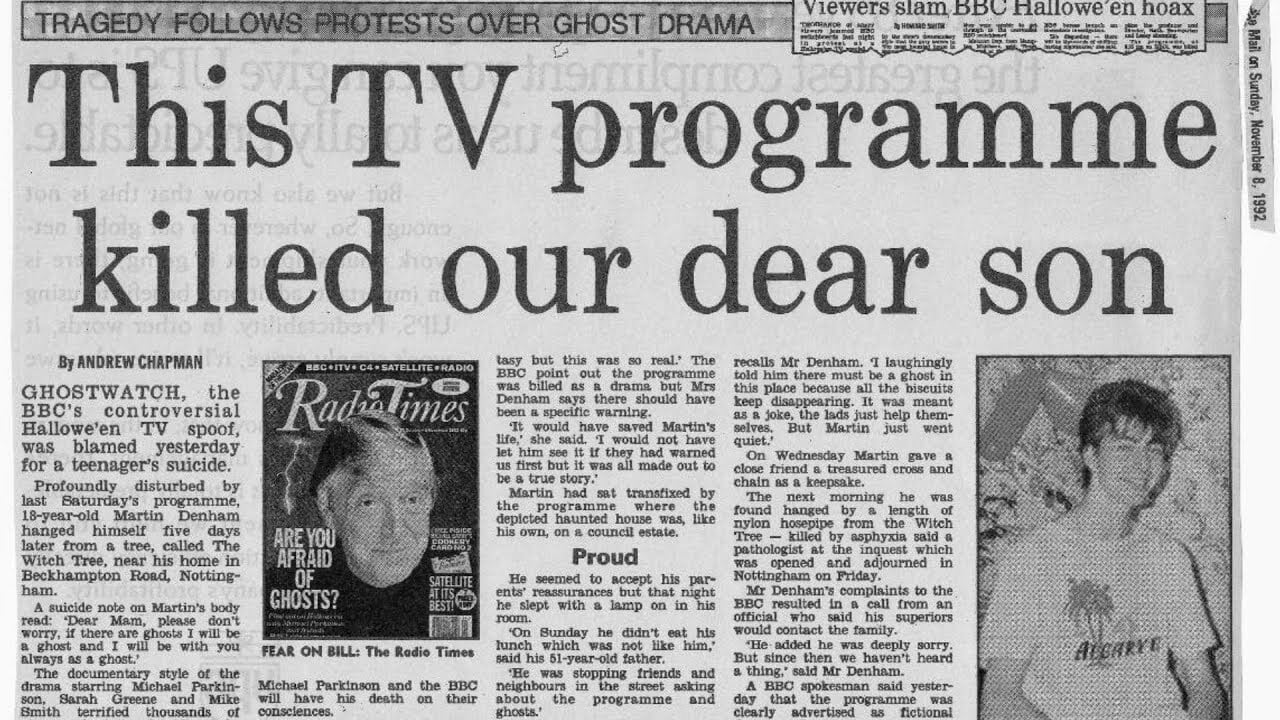

Directed by Lesley Manning from a script by Stephen Volk, Ghostwatch was a supernatural drama dressed up as a live TV show with BBC presenters Michael Parkinson, Sarah Greene, Craig Charles and Mike Smith playing themselves. It’s hard to imagine now, but it fooled millions of viewers and caused a huge backlash. There were reports of children suffering from PTSD after seeing it, someone tried to bill the BBC for their husband’s soiled trousers, and one poor young man killed himself.

Originally conceived as a six-part series with a “live” finale, Ghostwatch was condensed into a single feature-length episode with a lot of backstory. It introduces the Early family of Foxhill Drive, Northolt, London—mother Pam (Brid Brennan) and her two daughters Suzanne (Michelle Wesson) and Kimmy (Cherise Wesson), the latter sisters in real life—a seemingly ordinary family in a seemingly ordinary neighbourhood.

The Earlys have been tormented by paranormal phenomena for months, from banging sounds and bent spoons to scratch marks appearing on Suzanne’s face and a malevolent ghost called Pipes haunting the cupboard under the stairs. Ignored by the council and mocked by the press, they’ve asked the BBC to document their plight.

For anyone who knows the Enfield Haunting it’s a familiar story, but with horror it’s the telling not the tale that really counts. Right from the start, we’re plunged straight into the action at Foxhill Drive like it’s a real location report, with timecodes, booms bobbing in and out of view and the now-familiar markers of shot-on-the-fly TV. Back in the studio, Parkinson discusses the increasingly alarming footage with paranormal expert Dr Lin Pascoe (actor Gillian Bevan), while presenter Mike Smith (Greene’s real-life husband) takes calls from concerned viewers and worries for his wife’s safety as Pipes makes his presence felt in a number of imaginative ways.

What makes it all so powerful is that, bar the odd shaky performance, it looks and sounds exactly like a genuine documentary. They even use the 081 811 8181 number familiar from innumerable BBC programmes, including the kids’ show Going Live, which Greene hosted for many years. Back in 1992, viewers had an unshakeable trust in the BBC. So when it inferred this was a real haunting, it’s no wonder people believed what they were seeing. The presence of Greene and Parkinson helps to sell the idea, but it also twists the knife, because watching them becoming more and more rattled is deeply unsettling, like seeing your mum and dad scared.

And what scares. With his scarred face and spooky backstory, Pipes is a terrifying creation, helped by the fact that we only glimpse him in passing. The first occurrence comes early on, when viewers think they see a dark shape behind the curtains in the girls’ bedroom, but Parkinson and Dr Pascoe quickly dismiss it as a trick of the light.

However, as the night goes on, eagle-eyed viewers can spot Pipes haunting the background of various shots, reflected in patio doors and—in the scene that ruined poor 12-year-old me—emerging from behind those curtains only to disappear when the cameraman pans back again. Soon it seems he’s infected the whole programme, the TV studio, even the country, as we hear terrified viewers phoning in to say their children can’t stop looking at the screen.

And all this while the ‘fake’ phonelines were inundated with calls from real viewers saying much the same thing. Apparently 11 million people watched Ghostwatch live—that’s a fifth of the UK population—so Manning, Volk and co. really did prank a good proportion of the nation.

Watching Ghostwatch today, it’s easier to see the joins, but it remains a uniquely chilling experience. It didn’t have me shivering in the bathroom this time—I’m 41—but I did wake in the night wishing my house wasn’t quite so creaky and that there wasn’t a cupboard under the stairs, empty or otherwise.

Ultimately, the reason it stands the test of time is that it achieves what all great horror—from the shower scene in Psycho to Sadako coming through the screen in Ringu—aims for. It gets us somewhere we’re supposed to be safe, and after that, nowhere’s ever safe again.

Matt Glasby is the author of The Book of Horror: The Anatomy of Fear in Film.