‘Pete’s Dragon’ Director on Nostalgia, Kids, and Respecting Their Intelligence

We spoke to Pete’s Dragon director David Lowery at length recently when he was back in New Zealand to premiere his film, shot here with significant funding assistance from the NZ Film Commission. Last week we ran an excerpt in which Lowery talked about his experience shooting in New Zealand – today, as the headline suggests, we dive deeper into the themes of the film and what making a film starring kids and for kids entails.

FLICKS: Thanks for making me cry within a couple minutes of the film starting.

DAVID LOWERY: You’re welcome.

You’re a bastard. But thank you.

I always figured the ending would definitely get people. I was honestly surprised that the beginning has gotten people as much as it has.

Yeah, it’s a dark opening. But that’s the start to many kids’ stories, right, ‘something happens to the parents’. You’ve taken a really interesting approach visually, in terms of what we do and don’t see in that opening sequence. It’s impactful emotionally, it’s got a adrenalized component to it, kids can handle it, yet an adult cried. What’s that about?

I think it’s because as an adult, you understand exactly what’s happening. It was really important to me to make Pete four years old in that scene because I feel that as a four-year-old, you’re right in the cusp of understanding things in a new way. But he still had that naivety and by presenting that sequence entirely through his eyes, we were able to avoid the darkest elements of it because he doesn’t quite understand what’s going on himself. And because he doesn’t quite understand what’s going on, he’s able to emerge physically unscathed but also, emotionally, he’s not damaged. And had he been a little bit older, had he processed exactly what has just happened in a truly literal way, I think we would’ve had to show it a little bit more.

Also, when we meet up with him six years later, he wouldn’t quite be so happy-go-lucky. He might be a little bit more disturbed. But we caught him right at the right age to where he is able to process deep, sad feelings, but kind of get past them and let them recede into memory. And as a surrogate for the audience, go through a truly traumatic experience without really having to engage with what’s happened. And so that’s how I think we were able to present this in a way that wouldn’t damage children who are in our audience and send them crying through the theater. But at the same time, an adult watching it knows exactly what’s going on and is going to have a completely different emotional reaction.

There’s some dark shit going on in kids’ minds around death and scary creatures.

I remember that as a kid, I gravitated towards things that engaged that side of my imagination because I was curious about it. From a very young age, from probably around four or five, I was very interested in monster movies or vampires or ghosts or things involving death just because I was naturally curious about it. And so those movies appealed to me, movies that dealt with that appealed to me because it allowed… it gave me an outlet for that side of my imagination. It helped me contextualize things and understand things and there’s great value in that.

So, I don’t think there’s any harm in presenting children with the dark side of the world and with the dark side of life in a piece of entertainment, as long as you show them the flip side of that as well. And so, I think with Pete’s Dragon, the first five minutes is sort of a road map of the entire film because it gets pretty dark, gets pretty sad and pretty scary but then, things get better. And that is sort of the promise the movie makes to the audience in the first five minutes; things are going to be tough, but they’re going to get better. And if you just stick through it, you’ll get to the light at the end of the tunnel.

Pete’s obviously in the thick of the trauma when he meets Elliott. But he still finds a pretty logical question to ask a giant dragon, right?

Strictly logical, strictly logical. And also, up until that point it’s been largely wordless – that entire process. And that is the moment where we can clear the air and reset things. And that also is the moment where Elliott, for the first time, reacts in a way that is not monstrous and he reveals himself to be not a lumbering behemoth from some Lovecraftian mythology but in fact, a different type of creature. One who has different responses, different feelings, different emotions and so that question and the answer that Elliott gives is sort of a turning point in the movie. And it’s the moment where you start to clue audiences into the fact that this isn’t going to all be darkness. It’s not all going to be grim.

You display, in your film, a real confidence in your audience, avoiding many really literal signposts that we’ll often see in a kids’ film. I find that really interesting, particularly working under the umbrella of such a huge company as Disney. What sort of conversations happened around that? Like, “You’re not making it obvious enough what’s going on here”? Was there a push and pull tension around those sorts of issues?

Very little. Very, very little. There were a couple scenes where we explained things a little bit more or where something was too subtle and needed a little bit of underlining. But for the most part, everyone at Disney was very happy with how we told the story and with the respect we paid the future audience of the film. I always dislike it when movies are underestimating their audience. Whether that be me or the people I’m going to the movies with, or in the case of a children’s film, the kids that are going to see it. I think audiences are smart, they’re very literate – especially when it comes to media – and they know how to process information. They don’t need everything spoon fed to them. And there’s often an instinct to do that in studio filmmaking so as to appeal to the lowest common denominator. To make sure everyone gets the message, to make sure everyone leaves understanding exactly what happened.

But I think when you do that, audiences can tell that it’s happening and they reject it. I think audiences can – whether it’s conscious or not – tell when extra dialogue has been added in ADR to underline some fact that isn’t really all that important. I think they can pick up on those types of fixes that you do in post-production, so I wanted to avoid that. And I wanted, in the writing process, to really make a film that respects not only their narrative intelligence – their ability to follow a story and understand how things get from point A to point B without charting every single step along the way – but respects their emotional intelligence. And that was a really big deal to me, especially in terms of the kids who will be going to see this movie. To make sure that this is a movie that understands that children have a multitude of feelings. Feelings that are as complex as adults’ and that they deserve to have a movie that caters to those emotions. And that’s what we set out to do.

I think a really strong example of that is in the relationships between the main characters in the film. The emotional relationships are quite strongly spelled out by the actions and the way they interact with each other, and you avoid explaining how they fit together in an obvious way. There’s a confidence there that recognises if you’re bombarding children with information, that might not sink in anyway.

One of the things I love about the movie is when the little character Natalie is showing the family photos to Pete. And it’s a completely fragmented family coming from all sorts of different places. She’s like, “There’s my mom, there’s my dad, there’s his brother, there’s Grace [Bryce Dallas Howard’s character]”. Who, for all intents and purposes, is her mom, her step-mother. Even though we don’t know exactly how that relationship works. And she’s like, “And that’s our family.” And that’s the only explanation we have for it. We don’t go into the back story of what happened to Natalie’s mom, why isn’t she in the picture. We don’t go into the history of why Grace is in a relationship with a lumberjack. It’s just like, “Let’s give these characters history, let’s touch on it and understand the people will just pick up on what those relationships are.”

E.T. is obviously a reference point for this movie, but we never really went back and looked at it. One thing I did bring up a lot is how, in E.T., there’s this sequence where Dee Wallace-Stone is talking to Henry Thomas – Elliot – and they’re having an argument and she mentions something about his dad and he just says, “I can’t call dad, he’s in Mexico with Sally.” And she just gets upset for a second and walks out of the room, crying. And that made a big impact on me as a kid because I didn’t quite understand what that dynamic was and they never bring it up again, but it just subtly lies out the situation that this family has found themselves in. And what the emotional stakes are, where the dad is. It really subtly does that. And I reference that a lot when we were talking about how much we needed to talk about the adult side of things in this movie. Which is very little. We don’t need to deal with what the adults are dealing with because this is a movie for kids. But if we just add these little hints, like Spielberg did in E.T., you get a very well defined portrait of a family in its totality. We’re not just focused on the kids, we’re focused on the adults as well.

I think one of the reasons that my bloody crying started was the nostalgic sensation of the time period it’s set in, alongside the subject matter. It seems like you’ve avoided making an overtly nostalgic film, scoring cheap and easy points, which does seem to be horribly common at the minute. How critical to the film is the broad 80s era it’s set in?

There’s a bunch of different reasons. One of them is that the movie’s a fairytale, sort of, and most fairy tales start with “Once upon a time,” and “Once upon a time” means something that has happened in the past. So you want to set it in the past because there’s a tradition there, and there’s a sense that magic is more possible in the past. If it was in the present, I would question things a lot more. But if it happened in the past, I would be far more accepting of magical realism. And nostalgia’s a tricky thing because you don’t want to just soak in it. You don’t want to make a movie that is appealing to the sentimental side of nostalgia. But at the same time, it is a useful tool. And if you do it subtly, without hitting too many nails on the head, I think it can really transport adult audiences into not a different time and place, but into a mindset that is a useful mindset.

That’s exactly what happened with me while watching the film. It’s like, there’s a reservoir of stuff in here and some I’m aware of, some I’m not.

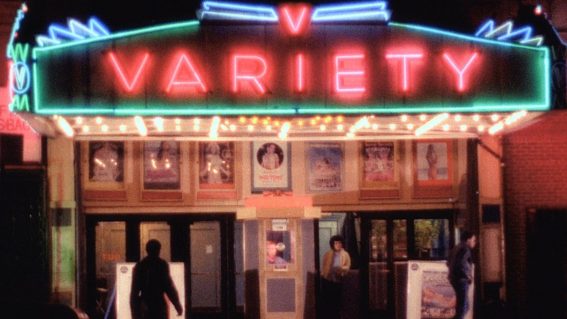

I set the movie in a time that looked like my childhood. It’s not any specific year, but I was like, late 70’s, early 80’s. I grew up in the early 80’s and so all my clothes were second hand and so they probably came from the 70’s. And there’s just like, that general sense of that look and feel of things. But we never did anything so explicit as to put a movie poster on the wall. When there’s a movie theater in town, we didn’t try to put a little nod to the 80’s by putting a certain movie title on the marquee. We kept it very vague and the hope is that you don’t think about it. You just watch the movie. Maybe you understand that the film is taking place in the past, maybe you don’t. It doesn’t really matter. Hopefully it’s a fact that just recedes into the fabric of the story and becomes unimportant.

You’re obviously taking advantage of all the filmmaking tools at your disposal in 2015-2016. But the film doesn’t feel like it’s native to this time period.

Yeah, I mean, I like old fashioned things. I’m very open about that. I like movies that feel handmade and I feel that modern technology makes it very easy for any piece of entertainment to feel slick and untouched by human hands. And there’s a value to that. No doubt about it. There are movies where that makes sense. I’m looking at this poster for Tintin right behind you and that’s a movie that makes the most of modern CG technology and works. And I have no issue with that. But I also really love anything that feels tactile, anything that feels textured. I love movies from decades past, when you could see the film grain in them and you could really feel that grain boiling. Few, very few movies are shot on film anyway, and modern film stock is so advanced at this point that you can’t see the grain anymore. And that’s fine. That’s great for some movies. But I appreciate that. And I like it, and that’s something that I always endeavour to do.

And so, I do take advantage of everything you can do technologically. The movie is full of invisible visual effects that you would never have been able to accomplish in the 70’s. Whether that’s taking two takes and gluing them together to get the best performance of two different takes or painting out something that annoys me in the background. I do that all the time. I’m constantly just painting things out. But the goal is for that to be invisible and for the film itself to feel as old fashioned and handmade as possible. And getting a giant CG dragon in there, to fit into that world was a little bit tricky but I think we did a pretty good job.

Meanwhile, over your shoulder, I’ve been looking at the poster for ‘Boy’. Taika Waititi famously didn’t cast the lead on that until basically the last second. Like, day before the production started. What was the casting process for you with the kids in this film?

It was thankfully not like that. We were ready for it to be that way if it had to be but we found Oakes Fegley fairly early on in the process. Our casting director, Debra Zane, did the usual nationwide search of looking all over the U.S. for the right kid and she saw thousands of kids. Like, 2600 I think, and distilled that down to a list of about 100 that I watched on tape. And then, I met 20 or 30 of those. And she told me very early on that she had met this one boy named Oakes, who she felt that I would really like and was very adamant that I meet him.

So, I went to New York and met him, and left that meeting and instantly called everybody I could at the studio and said, “We found Pete.” And they watched the video that made and the audition and all agreed. And so it was pretty easy. It was around July of 2014. So, a full six months before we started shooting. And so that was helpful in terms of giving him time to prepare. He was able to come to New Zealand early, spend some time in prep. It was really nice to have the comfort zone of having our protagonist cast that early on.

What’s different about working with kids – especially as a lead? I mean, is it a different approach to the rest of your cast?

It is, partially because they can only work a couple hours a day. So, that’s one thing right out the gate that makes it a different approach. You have to be much more direct and use your time in a different fashion because they just don’t have very much of it. Especially when they’re the leads and they have to carry the entire movie and you’re shooting for 80 days and they have to be there every single day but at the same time, they only can work four hours of each day. You really have to approach it differently for that reason. And that’s a purely technical reason. But in terms of working with kids, I really just like to create a context in which they can be themselves and then, step back and just film them.

That’s what everyone in casting is looking for, right? Forgive me, if I get this wrong, but you’re essentially looking for the person to be the person you see on the screen.

Exactly.

So, the honest emotional responses, the way that that child would react to something similar in real life. There’s not much artifice going on, is there?

There’s much less artifice. That’s not to say that they’re not trained or not skilled as actors, because they are. And they have to be if they’re going to carry a movie for that long. That’s incredibly hard work. But the fabric between fantasy and reality is much thinner when you’re a kid. And they’re able to inhabit these worlds or these characters in a much more direct fashion than I think adults are able to. And so, you’re always looking for the children who not only have that innate talent and that innate skill as performers, but the kids who can forget that you’re making a movie and just are able to be themselves at the same time. And it’s a real tricky balance, but you know when you see it.

That’s why, when Oakes walked through the door, I just knew he was going to be the right kid. Because it’s just something in their presence that tells you, “I want to watch them. I want to just turn the camera on and film them and see what they do.” And that’s how I like to work with them. I really like to let them direct it to a large extent. I like to understand what we’re doing through their eyes. I want them to sort of lead the show. And I’ll be there to provide guidance and to sort of contextualize things. But they’re the ones who are kids and who know how a kid would respond to something. So, as long as that gives them something to respond to, I’m just going to follow their lead in terms of what that response is

Were there any moments where you had to stop your supervision of all the moving parts and work with the kids by just bringing yourself down to this level of a simple emotion that you’re trying to convey?

That’s the best part about it is when you can kind of ignore all of that machinery. Because it gets really stressful if you’re trying to pay attention to all of it. So having an actor to talk to is actually really wonderful because you can use it as an excuse to ignore every other decision you’re supposed to be making at that moment. But it definitely is tricky to forget about the hundreds of people that are working for you at any given shot when you’re making a movie.

Every day there’s an army of technicians and craftsmen and women and really skilled artists who are there to execute your vision. And you need to be ready to answer questions and communicate with all of them and let them know how they can help you. Because that’s what they’re there to do. They are there to help you. Often you don’t know, as a director, what you’re doing next. You don’t have every answer and that’s okay. But they’re there to help you figure those answers out. That said, it can be incredibly taxing and it is tough for someone like me, who doesn’t even enjoy talking that much

I’m not that good at communicating, especially on the spot. And so, all that being said, it’s really great to be able to get tunnel vision every now and then and just get to work with the actors and focus on what they need and what we’re doing on the scene and how we’re going to preform it and how we’re going to block it. And especially when they’re kids, because they have such a fresh perspective and so much enthusiasm for the process even when they’re really tired, because they had to get up really early. It allows all of the noise of the production to recede into the background and it really reminds you of what the focus needs to be.

I don’t know if that answers the question but the difference really is that you’re focusing on just one thing and you’re there. And when you’re working with kids, they need that attention from you. And so, it’s a wonderful excuse to focus only on them, but also helps me just remind myself what it is we’re actually doing. Because I can get caught up all day long in the colour of someone’s pants, and trying to pick out the right pair of shoes. But the end of the day, it doesn’t really matter what colour they are as long as the person wearing them is doing the right thing. And that’s what my job ultimately comes down to.

Pete’s Dragon opens Sept 15. Click for movie times and more info

Watch the ‘Pete’s Dragon’ trailer