Interview: ‘Utu Redux’ director Geoff Murphy

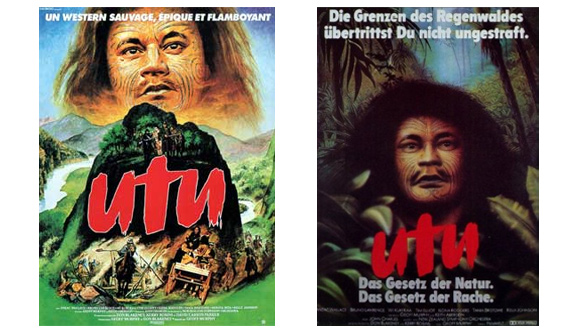

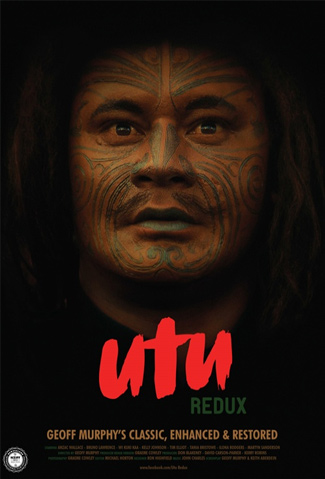

Local classic Utu has been restored and revitalised, giving audiences the opportunity to see Geoff Murphy’s 1983 classic on the big screen looking better than ever. Murphy and cinematographer/producer Graeme Cowley have thoroughly restored the film, a process made all the more difficult by the original master negative no longer existing. As it had been disassembled and re-edited to make the shorter international version of the film in the 1980s, a painstaking three-year process was required to complete the new edit, overseen by Murphy and original Utu editor Michael Horton.

Audiences will be able to see this new version of the film in its two-week limited release across New Zealand from November 21, entitled Utu Redux. Geoff Murphy was kind enough to take the time to answer our questions about the film and restoration process.

Hello from Flicks. What have you been up to today?

Nothing much. The weather is bloody awful and it’s cold. I set my electric blanket on ‘2’ and lay in bed cooking for a couple of hours. It was good.

What initially drew you to make Utu?

It’s hard to remember. I began working on the script about forty years ago. The idea came from a book by James Cowan called Tales of the Maori Bush. One of the stories was a detailed account of a bush trial which formed the basis of the final scene in Utu. It was a powerful story, just begging to be made into a film. At the time there was no Film Commission, no tax shelter, a hostile television establishment and so the prospects of any sort of funding were non existent. I guess it was a bit of a fantasy.

At one stage I approached television with a treatment for a fifty minute version. They rejected it and suggested a possible twenty five minute one. There was no way I was going to destroy a really good idea to suit the politics of television so I rejected this. Even later, after the Film Commission had been set up, it seemed too ambitious a project to be possible under the existing funding structures so I submitted a more modest film called Goodbye Pork Pie. The extraordinary success of this film, plus the introduction of tax shelter funding made Utu possible.

What was the filmmaking landscape in NZ like at the time?

I suppose by ‘film making landscape’ you mean the conditions for producing product for New Zealand’s national cinema. These are films made for and by New Zealanders that tell stories that are relevant to New Zealand’s experience and culture. The landscape for such beasts was bleak. It has always been bleak and probably always will be. The main reason for this is that feature films cost so much, that it is almost impossible to recover your costs in the New Zealand market place, and such films do not often sell widely overseas. This being the case, you would have to be mad to seriously contemplate making such a film and even crazier to invest in one.

As a result, it takes an enormous commitment fuelled by insatiable passion to get such a film off the ground. Even with all this, it probably can’t happen without some form of patronage. Usually this patronage is supplied by the New Zealand Film Commission. Unfortunately, the Film Commission doesn’t seem to see its role as one of a patron, but rather as one of a controller.

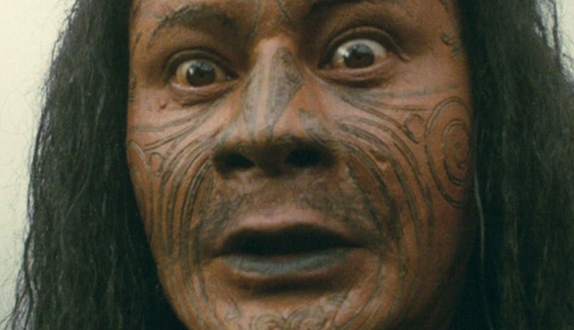

Photo by Graeme Cowley

How ambitious a project was the film in that context?

Utu was a tax shelter film. In this case, the role of patronage was taken by investors who were insured against loss by the granting of tax advantages. This is a scheme that, if used judiciously, could have funded modestly budgeted features for quite some time. Unfortunately foreign producers got in on the act and exploited the tax loophole remorselessly. It became a kind of feeding frenzy with many foreign films with foreign directors and foreign stars making expensive and rather trashy pictures until the government stepped in and cried ‘No more!’

Utu was really too expensive to be comfortably accommodated in the tax rules that existed. As a result, the deals became under intense scrutiny from the tax department and only just survived. So the film was ambitious enough to push the funding arrangements almost to breaking point. It was the biggest New Zealand film up to that time.

What were your thoughts when Utu began to attain international recognition, and how would you describe the impact on your career?

Utu received strong reviews and was shown in major film festivals all over the world. It definitely established me internationally as a director of some importance. Consequently job offers began to materialize, mostly from the USA and Australia. Goodbye Pork Pie, for all its outrageous success in New Zealand, did not have nearly the same international cachet. Utu’s international profile was essential to me because at that time the tax shelter had been stopped and it was becoming even more difficult to get a picture up in New Zealand. It meant I could work.

How did you feel about the film being recut for an international release?

My thoughts at the time of the Utu re-cut were very confused. Utu had left me physically and emotionally exhausted, I was in the middle of a marriage break up and found it difficult to understand the motivations for it and the legality of what they were doing. After all, I had hired the producers after developing the idea for some ten years. According to them, they now owned the production and could do what they liked with it. This, they argued, is because writers and directors have to assign their rights to the production company if the film goes into production. I hated the idea of a re-cut. I couldn’t understand their insistence that the film be made ‘more accessible’ when it had already been seen by more than three hundred and fifty thousand New Zealanders.

At what point did you begin to consider the long term impact of that recutting?

Although the re-cut was presented to me as a marketing move for foreign sales, I was always aware that the re-cut version could become what history regarded as the final version of my film. I was particularly unhappy if this was to be the case in New Zealand and indeed the producer’s cut was released in New Zealand on video and made it onto TV here. Fortunately, the re-cut didn’t make a huge amount of headway because most people seemed to prefer the original version.

When did you realise Utu needed to be rescued and preserved?

It was Graeme Cowley, the director of photography on Utu who first brought the state of the picture to my notice. He had seen it on Maori Television and had been appalled by the state of the print. He approached me to see if we could do something about rescuing it. I was skeptical at the time because of the cost involved. We would have to raise well over a hundred thousand dollars to re-master a film that was thirty years old. It didn’t seem realistic that the re-mastered film would have great potential at the box office, so this money would have to come from sources that recognized its cultural and historical value. That didn’t sound easy to me.

Did that come with a sense of urgency?

Once we began to seriously examine what was required, we discovered that the producers had had the original negative cut rather than a duplicate, to make their version. We also discovered that although the original negative, which was Fuji, had stood up fairly well, any duplicates, which were on Kodak stock, had deteriorated markedly. Since we were going to have to use a fair bit of duplicate material to complete our task, there was some urgency to identify what we needed and get it scanned electronically.

How complex and time-consuming has the restoration been?

The first part of the task was to re-assemble the film in its original form. It took many months of searching through archives to identify all the elements. Once this was done, the film was assembled with and dupes identified. We then set about going through the old edit and making any changes that we felt would enhance it. Myself and Mike Horton, the original editor, carried out most of this work and it took about a dozen sessions. We made hundreds of changes. Most of them were very small, removing a few seconds or less here and there to make things flow better. From memory we removed four whole sequences that we felt did not have enough bearing on the film to justify them remaining.

By the end of the process we had removed about ten minutes. Once this was complete, the picture was re-graded. This is where Park Road Post came into its own. Every shot was examined and tweaked to get the best out of the original material. Modern electronic grading enabled us to enhance the duplicated material and match it to the quality of the original negative. The end results were spectacular. The film now looks better than it did when it was first screened.

Photo by Graeme Cowley

How do you think the film has been improved by this process?

The re-edit has made the film a lot smoother and more focused. The electronic grading makes it glow. However, one of the greatest benefits has come from the re-working of the sound. Sound equipment has advanced enormously in the last thirty years. So has the level of expertise of the technicians. The people associated with Park Road Post have since worked on all the The Lord of the Rings projects as well as Avatar and a number of other major international projects. Some of them are now Academy Award winners and they all gave Utu their undivided attention. The late Mike Hopkins, one of the Academy Award winners, was particularly brilliant. The result is a film that sounds like it was made in Hollywood yesterday.

What would you like to see happen in terms of the broader preservation of NZ films?

This is a complex question. Preservation at high quality is a very expensive proposition. There are hundreds of films already where preservation is a question. It would seem probable that only a selected number can be done. This raises a number of questions: How many? What criteria would be used to decide which films to preserve? Who would make the decision? At what quality should the preservation be done? It seems like a new committee will need to be set up as I don’t think any of the existing ones will be adequate.

Those who hate it the most would probably be the ones who should be made to see it

Who would be the best, and worst, possible people to bring along to your film?

I don’t think it matters who comes to the film. Those who hate it the most would probably be the ones who should be made to see it. I have had thirty years to think about it and I have come to the conclusion that it is an excellent film. Other people’s opinion of it no longer matters to me.

What was the last great film you saw?

I am now nearly 75. It is a lot harder to get excited about anything these days. ‘Great’ is a pretty powerful epithet to describe any film. I have seen some pretty good ones though. I enjoyed The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel, No Country for Old Men, Argo, The Intouchables, and Beasts of the Southern Wild to name a few.

What are you thinking about doing next?

I’m retired. I have been engaged in writing my memoirs. It’s pretty slow going and I wonder if I’ll ever finish. It seems an almost arrogant thing for a Kiwi bloke to be doing. I mean, who the hell would be interested in what I’ve been doing? Still, I’ll worry about that when (and if) it gets finished.